as the nigerian state retreats, armed groups rise

bandits, insurgents, and militias are taking over where the government has disappeared.

Last week, gunmen stormed Gobirawa Chali, a remote mining village in Zamfara State, northwestern Nigeria. They arrived on motorcycles and opened fire. At least 20 people were killed, some while working, others while asleep. There was no response from authorities. No arrests. No word on who sent them. For locals, it was just another night of violence in a region where attacks like this have become routine.

This wasn’t an isolated massacre. It was part of a broader pattern. Across Nigeria, patterns of violence point to a shrinking state presence and the growing influence of armed groups stepping into the void.

Across northern Nigeria, and increasingly across the country, armed factions are filling the vacuum left by a vanishing state. What began with Boko Haram’s insurgency in the northeast has metastasized into bandit militias in the northwest, ethnic militias in the Middle Belt, separatists in the southeast, and criminal networks that span nearly every region. The government isn’t

just losing ground, it’s stepping back. And others are stepping in.

a crisis years in the making

Nigeria’s security breakdown didn’t start yesterday.

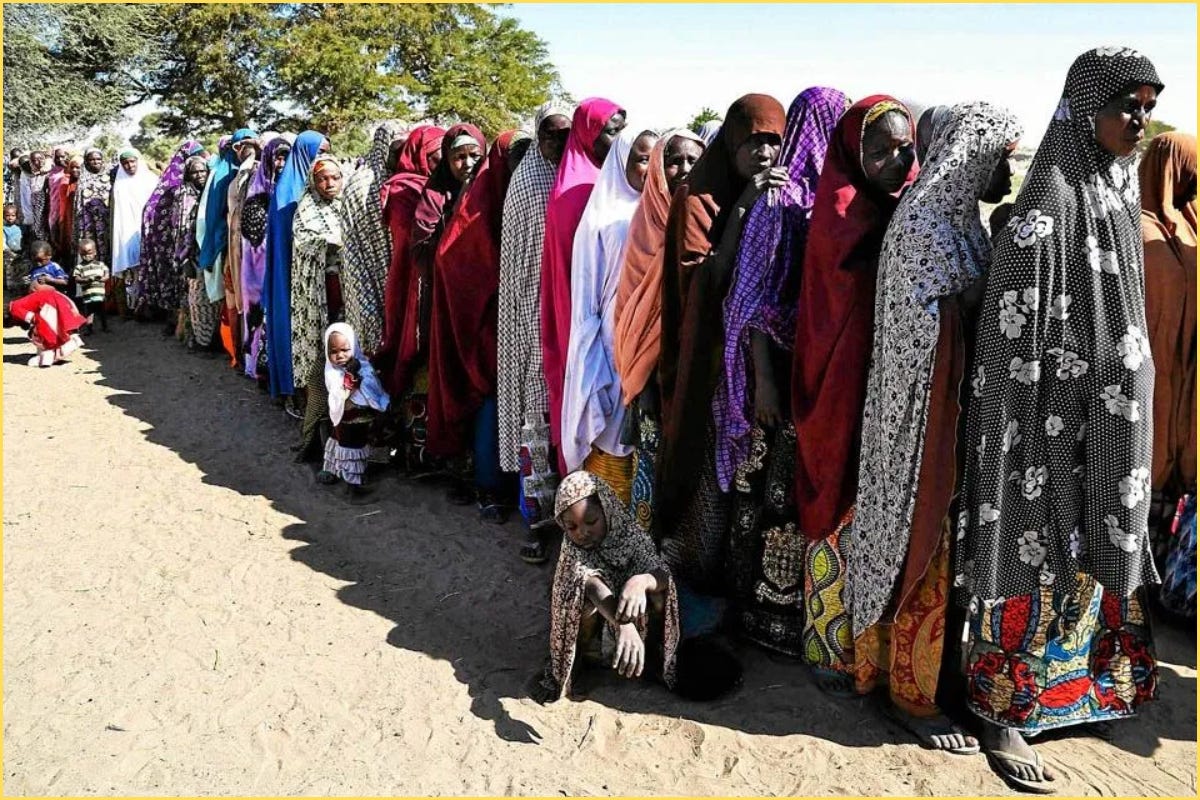

Boko Haram first emerged in 2009, feeding off deep frustration over poverty, police abuse, and corruption in the northeast. Since then, the group and its splinter faction, the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP), has killed tens of thousands and displaced millions. Entire towns across Borno, Yobe, and Adamawa were once under militant rule. Schools were burned. Markets bombed. Aid workers executed.

Though the military has reclaimed some territory, the insurgency never truly ended. Today, Boko Haram and ISWAP still ambush convoys, kidnap civilians, and control trade routes.

In the northwest, a different threat has taken root, one that mirrors the same collapse. What began as local clashes between farmers and herders, and cattle raiding in states like Zamfara and Katsina, has evolved into large-scale banditry. These are no longer ragtag gangs. Some groups have thousands of fighters, wield military-grade weapons, cross state lines freely, and impose their own taxes on villages. In many areas, they are the authority.

This violence is deeply tied to illegal mining. A 2024 field study by the Center for Democracy and Development (CDD) found that some mine owners have armed and funded bandits to protect goldfields from rivals. Nigeria’s Minister of Solid Minerals, Dele Alake, confirmed that powerful figures, including ex-military officers and politicians, are behind much of the violence, using banditry as a shield for illegal operations.

What’s emerged is a criminal ecosystem: violence as both a weapon and a business model. Though the federal government designated bandits as terrorists in 2021, enforcement remains weak and inconsistent.

Security forces are overstretched and underfunded. Billions in defense spending have been lost to procurement scams. Soldiers are often deployed without proper gear. Residents report that reinforcements arrive hours, or days, after an attack, if they come at all.

Fear has become the default.

the middle belt is burning

While the spotlight often lingers on the northeast and northwest, central Nigeria, the Middle Belt, is becoming the latest epicenter of violence.

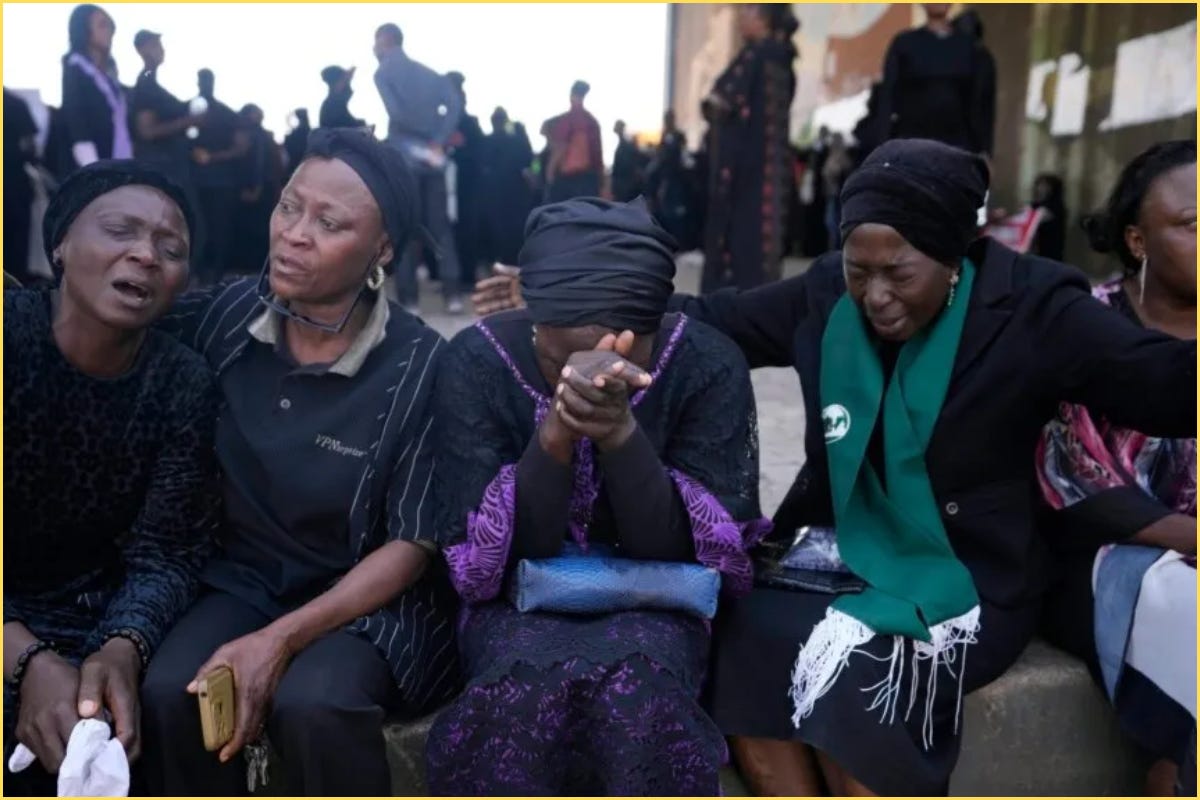

Just last month, over 150 people were killed in attacks across Benue and Plateau states. In the village of Zike, more than 50 residents were massacred during a midnight raid. Days earlier, coordinated strikes in Benue’s Logo and Ukum local government areas left dozens dead.

The violence is usually framed as religious or ethnic, Muslim Fulani herders versus Christian farming communities. But the root issue is land: who owns it, who uses it, and who decides. Years of unresolved tensions, environmental pressure, and a collapse in local conflict resolution have turned land disputes into bloody, sectarian wars. A fight over a grazing path can quickly escalate into a series of revenge killings.

Plateau has hosted a military task force for over 20 years. Still, the killing continues. Between December 2023 and February 2024, Amnesty International recorded over 1,300 deaths in the state. The Irigwe Development Association says at least 75 of its members have been killed since December, even with a military presence nearby.

Survivors often describe the army as slow to respond and ineffective when it does. Politicians label the attackers as “terrorists” or talk about “genocide,” but few address the real causes: land scarcity, migration pressures, and the decay of traditional mediation systems. In the void, communities are organizing their own militias.

Trust in the state is nearly gone.

a state losing its monopoly on violence

What’s unfolding is no longer regional. It’s national.

In the northeast, Boko Haram and ISWAP are still mounting deadly attacks. a few days ago, a landmine explosion between in Borno State killed at least 26 people, including women and children. Militants have used drones, bombed roads, and continued to outmaneuver military offensives.

In the northwest, bandit groups operate with impunity. In Zamfara’s Maradun area, more than 50 people were kidnapped in one raid. These fighters control entire stretches of rural terrain, cross into Niger with ease, and profit from gold smuggling. Their operations often enjoy protection from elite sponsors.

In the Middle Belt, the conflict between herders and farmers has morphed into systemic bloodshed. The April 2024 massacre in Zike wasn’t unique, it was part of a broader trend of ethnically tinged mass violence. Amnesty recorded 1,336 killings in Plateau over just three months.

In the southeast, separatist militias now enforce sit-at-home orders, attacking both civilians and security forces. In May 2024, five soldiers were killed in an ambush. Pro-Biafran groups now operate with growing military sophistication, challenging the government’s authority outright.

In the Niger Delta, oil theft and sabotage remain rampant. Despite military operations, October 2024 saw the destruction of 23 illegal refineries, and the seizure of 12,000 liters of stolen crude. The scale of theft suggests these efforts barely scratch the surface.

According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), Nigeria saw more than 4,000 political violence incidents between December 2023 and November 2024, with at least 9,355 deaths. The northwest alone experienced over 1,000 violent events.

Every region has at least one armed group acting with near-total impunity. The pattern is consistent: a hollowed-out state, entrenched corruption, and civilians trapped between predatory actors.

climate, corruption, and collapse

This crisis isn’t driven by politics alone. It’s also environmental and economic.

Desertification is creeping south, shrinking farmland and water sources. Herders are forced to migrate farther, sparking new conflicts with farmers. Droughts are more frequent. Growing seasons are shorter. In a country already prone to land disputes, these pressures are deadly.

Meanwhile, Nigeria’s borders, especially with Niger, Chad, and Cameroon are porous. Weapons move in as displaced people move out. Fighters cross freely. Armed groups thrive.

Illegal mining now fuels much of the violence. In Zamfara and Katsina, bandits not only protect goldfields but run them. The minerals are trafficked through networks stretching into Libya and Chad, with proceeds funding more weapons, recruitment, and territorial control.

The economy is in crisis. Inflation is high. The naira is weak. Over 130 million people live in multidimensional poverty. In many places, the informal economy, and the rule of militias, is all that remains.

Corruption feeds it all. From federal ministries to local councils, money disappears through scams and patronage. Public services barely function. Security budgets evaporate. It’s not a secret. Most Nigerians understand the game and know they’re not the ones winning.

What’s left is a cycle of violence, poverty, and despair. And in many places, people aren’t waiting for help. They’re picking up arms.

where this is headed

The signs are clear.

Large parts of the country are beyond government control. Millions are displaced. Institutions are hollow. Militias are growing. Violence is creeping south and across borders.

And still, Nigeria’s political class focuses on campaigns, court cases, and foreign trips. While they posture, the country quietly unravels.

This isn’t the kind of collapse that makes headlines overnight. It creeps in, village by village, state by state, until the rot becomes national.

Until the question isn’t “why is there violence here?”

But “why is there still peace anywhere?”

sources/footnotes

AP News, Gunmen kill at least 20 people in mining town in northwestern Nigeria, 2025

CNN, Gunmen kill at least 20 people in gold mining village of Nigeria’s Zamfara state, 2025

Dr. Murtala Ahmed Rufa’i, “I AM A BANDIT”, A decade of Research in Zamfara State, 2021

International Crisis Group, Violence in Nigeria's North West: Rolling Back the Mayhem, 2020

The Global Observatory, Northwest Nigeria Has a Banditry Problem. What’s Driving It?, 2024

Human Rights Watch, Spiraling Violence: Boko Haram Attacks and Security Force Abuses in Nigeria, 2012

United Nations OCHA, Nigeria Humanitarian Needs Overview 2024

Reuters, Surge in attacks signals jihadist comeback in Nigeria's northeast, 2025

Premium Times, Analysis: Despite inflicting heavy losses on bandits in 2024, Nigerian military faces daunting task, 2024

Blueprint.ng, Solid Minerals and Banditry in Zamfara, Niger, 2024

The Conversation, Nigeria’s illegal gold trade – elites and bandits are working together, 2025

Al Jazeera, Nigeria labels bandit gangs 'terrorists' in bid to stem violence, 2022

Transparency International, Nigeria's defence sector: Persistent corruption risk amidst escalating security threats, 2025

NPR, Attack leaves at least 40 people dead in Nigeria, the country's president says, 2025

Financial Times, Nigeria's spiralling rural violence heaps pressure on president, 2025

France 24, Intercommunal violence kills dozens in central Nigeria, 2025

International Crisis Group, Herders against Farmers: Nigeria's Expanding Deadly Conflict, 2020

Amnesty International, Killing of 51 People Is an Inexcusable Security Failure, 2025

Humangle, Silent Emergency: The Unending Cycle of Ethnic and Religious Violence in Nigeria’s Middle Belt, 2025

Al Jazeera, Roadside bomb blast kills 26 in Nigeria’s restive northeast, 2025

SBM Intelligence, Your Window Into West Africa, November 2024

Daily Trust, Bandits kill 28 in fresh attacks in Zamfara

AP News, Gunmen kidnap at least 50 people in northwestern Nigeria, 2024

Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime: Armed bandits in Nigeria

Amnesty International, Human rights in Nigeria

ISSAfrica, Lake Chad Basin insurgents raise the stakes with weaponised drones, 2025

Al Jazeera, Separatists kill at least 11 people in southeast Nigeria, army says, 2024

Sahara Reporters, Sit-At-Home Order: South-East Governors Condemn Killing Of Nigerian Soldiers In Abia, 2024

The Guardian Nigeria, Security heightens over IPOB’s sit-at-home order, 2024

The Premium Nigeria, Nigerian navy destroys 23 illegal refinery sites in October – Official, 2024

ACLED, Nigeria Violence Dashboard, Dec 2023 to Nov 2024

TIME, Land Conflict Has Long Been a Problem in Nigeria. Here’s How Climate Change Is Making It Worse, 2018

United Nations, Climate change fuels tensions in Nigeria, 2024

CFR, Violent Extremism in the Sahel, 2024

Humangle, Civilians, Gov’ts on The Losing End As Gold Smuggling Booms in Africa, 2025

Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, Armed bandits in Nigeria

National Bureau of Statistics (Nigeria), Multidimensional Poverty Index 2022