house of saud, house of secrets

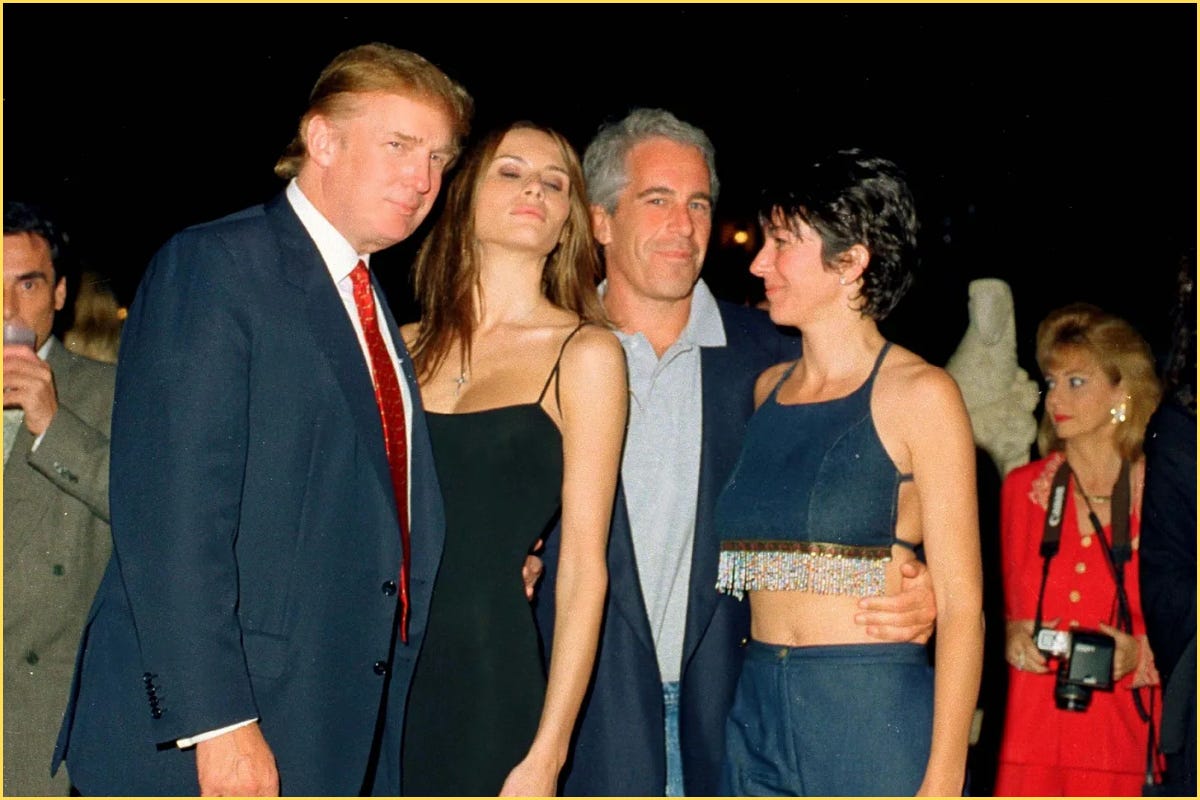

a single photograph of mbs with epstein could hold geopolitical and personal leverage capable of reshaping alliances and power plays far beyond what the image alone reveals

A photo can be a diplomatic statement, a threat, or a souvenir.

Last week, The New York Times ignited a wave of backlash after revealing a framed photograph of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman or MbS smiling alongside Jeffrey Epstein, framed on the wall inside Epstein’s Manhattan mansion.

For a man whose residences were famously wired with hidden cameras and microphones, nothing was displayed without purpose. The implication was immediate: MbS wasn’t just a visitor, he was in the gallery of leverage.

This isn’t happening in a vacuum. MbS is already navigating one of the most volatile geopolitical tightropes of his career, the stalled but very much alive talks to bring Saudi Arabia into the Abraham Accords, formally recognizing Israel.

Publicly, Riyadh says it will only sign if Palestine is granted a clear path to statehood with East Jerusalem as its capital. Privately however, U.S. and Israeli officials push for normalization, promising weapons, tech investment, and security guarantees. In the Muslim world, especially considering what is going on in Gaza, such a deal would be seen as betrayal.

Now add this, mounting evidence suggesting Jeffrey Epstein may have been working for Israeli Mossad, and was running kompromat (means compromising material) operations on elites across the globe. In that light, the MBS–Epstein photograph is a pressure point. And the story that unfolds from there ties together an unlikely chain: the flamboyant Saudi arms dealer Adnan Khashoggi, the kompromat collector Epstein, the crown prince in the crosshairs, and the murdered journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

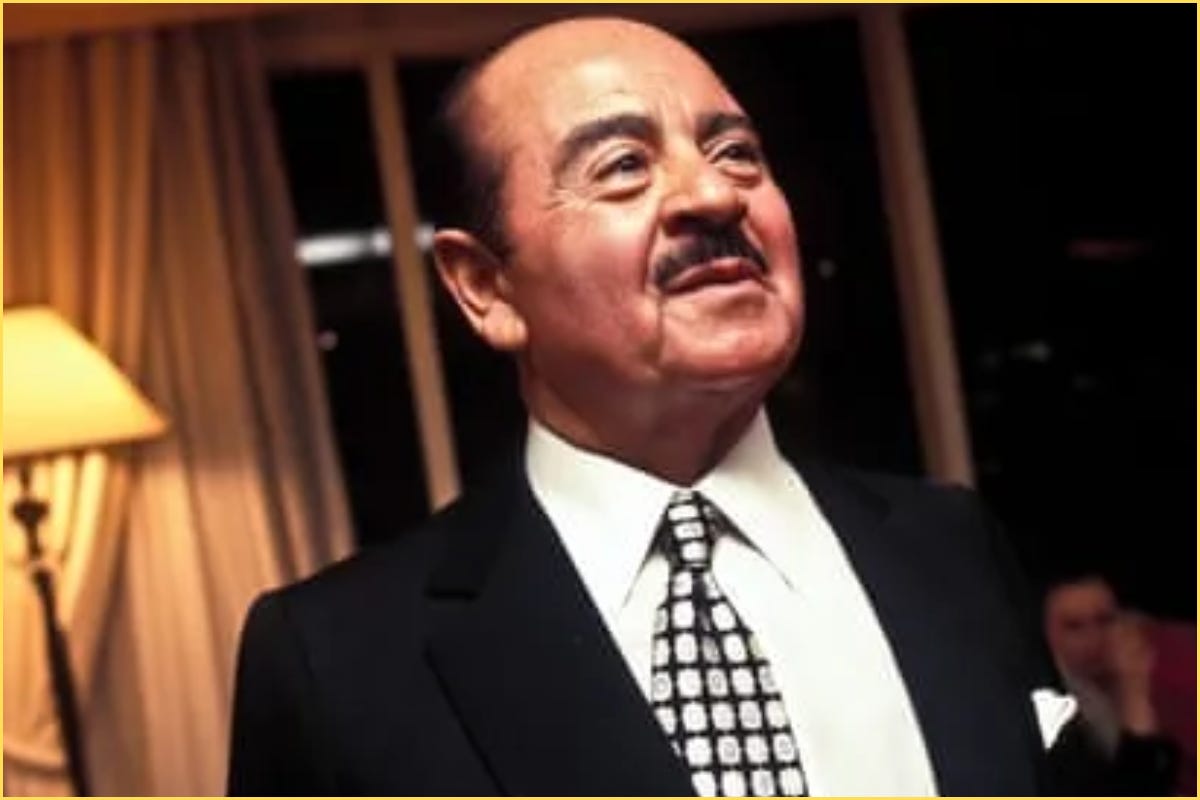

the original broker of power

Adnan Khashoggi wasn’t officially a royal, but he was deeply tied to the House of Saud regardless. The son of King Abdulaziz’s personal doctor, born in Makkah, he became one of the most notorious and well-connected arms dealers of the 20th century. His company, Triad International, functioned as a global clearinghouse for moving weapons, money, political favors, and covert influence between governments, cartels, and intelligence agencies. Public records, court cases, and investigative biographies confirm that he had longstanding dealings with U.S., British, and Israeli intelligence figures. Though the depth and formality of those ties remain debated. He built a reputation for brokering “impossible” deals in the shadows.

His public image was one of excess with fleets of yachts and private jets, villas on the French Riviera, and palatial estates hosting wild parties where oil sheikhs mingled with Hollywood actors, fashion models, European royalty, and covert operatives. Guests whispered about mountains of cocaine, endless champagne, and a rotating cast of escorts flown in from every continent. The parties weren’t just decadence, they were intelligence goldmines, carefully staged honey traps where celebrities, politicians, CEOs, and even royals could be compromised on film or tape.

Behind the glamour, Adnan’s real currency was the intelligence he controlled. Dossiers, compromising materials, and backchannel access to leaders and operatives from Washington to Tel Aviv. Former associates and intelligence leaks have claimed he trained younger operators, including Jeffrey Epstein, in the dark arts of surveillance like how to wire a room without detection, conceal cameras in ornate décor, and build archives of compromising material that could make allies obedient, rivals compliant, and targets permanently under his influence.

In this view, Adnan was selling the means to own people outright, and he understood that in the highest echelons of power, leverage was worth more than gold.

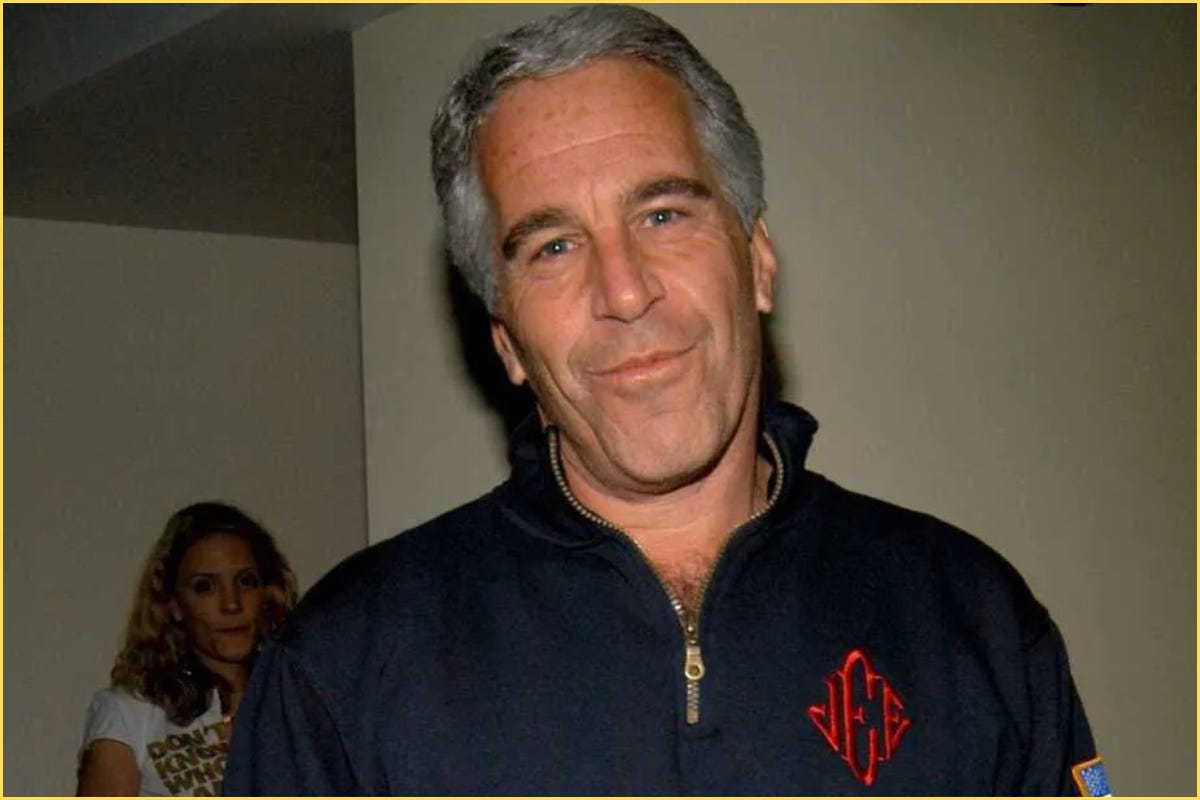

the collector of compromise

By the time Jeffrey Epstein was firmly embedded in elite social and political circles, he had taken the Adnan model and pushed it to an industrial scale. His properties, from his Upper East Side townhouse to Little St. James, were rigged for constant surveillance, with both hidden and visible cameras in bedrooms and common spaces, all feeding into a private control room.

Publicly released interior photos show visible camera mounts inside his New York townhouse, alongside a curated gallery of power: framed images of presidents, tech titans, and, crucially, a portrait of Mohammed bin Salman on the wall. Earlier court filings also revealed that Epstein possessed a foreign passport (Austrian passport) listing a Saudi address and bearing entry stamps from the 1980s, a detail which his lawyers brushed off as a “security measure,” but which hinted that his ties to the Gulf went back decades.

Put together, the kompromat-ready surveillance setup, an address book dense with Gulf and Israeli names, a Saudi-linked passport, and the prominent display of MbS’s portrait in a space purpose‑built for leverage, the intelligence‑operation theory gains weight. Whether MbS was an intended target or a willing participant, the image suggests that Epstein’s reach extended into the very heart of Saudi power, or that the heart of Saudi power willingly stepped into his web.

reformist autocrat or reluctant subject?

Mohammed bin Salman’s rise to power was meteoric but far from accidental. The favored son of King Salman, he maneuvered ruthlessly through the opaque hierarchies of the royal court by outflanking rivals, sidelining senior princes, and cultivating foreign patrons eager for a young, pliable partner in Riyadh.

His ascent was cemented in 2017 with the so‑called Ritz‑Carlton purge, when dozens of billionaires, ministers, and potential challengers were detained under the guise of an anti‑corruption drive, reportedly coerced into handing over billions in assets.

He branded himself abroad as a reformer, allowing women to drive, curbing the religious police, opening the kingdom to entertainment and tourism, but domestically built a climate of fear, with secret detentions, surveillance of dissent, and tight control over the press. Behind the glossy Vision 2030 marketing lay the blunt truth, survival meant absolute power for MbS.

His presence in Epstein’s orbit is more than a footnote to that story. According to the book Blood and Oil, MbS’s taste for extravagance has included month‑long private‑island parties with hundreds of foreign models, lavish spending on yachts like the $500 million Serene, and palatial properties in Europe. This is behavior that echoes the excesses of Adnan Khashoggi’s era.

If Adnan actually mentored Epstein in the mechanics of kompromat, then MbS’s proximity to that network is not a trivial coincidence. It suggests a possible overlap between Saudi political power and an apparatus long suspected of Mossad blackmail operations.

In Epstein’s house, walls were not decoration, they were potential evidence lockers. For a crown prince juggling a Saudi rebrand, sensitive normalization talks with Israel, and internal royal rivalries, any credible link to such an apparatus is more than bad optics; it is a latent weapon others could wield, with repercussions for his grip on power, the kingdom’s alliances, and its standing in the Muslim world.

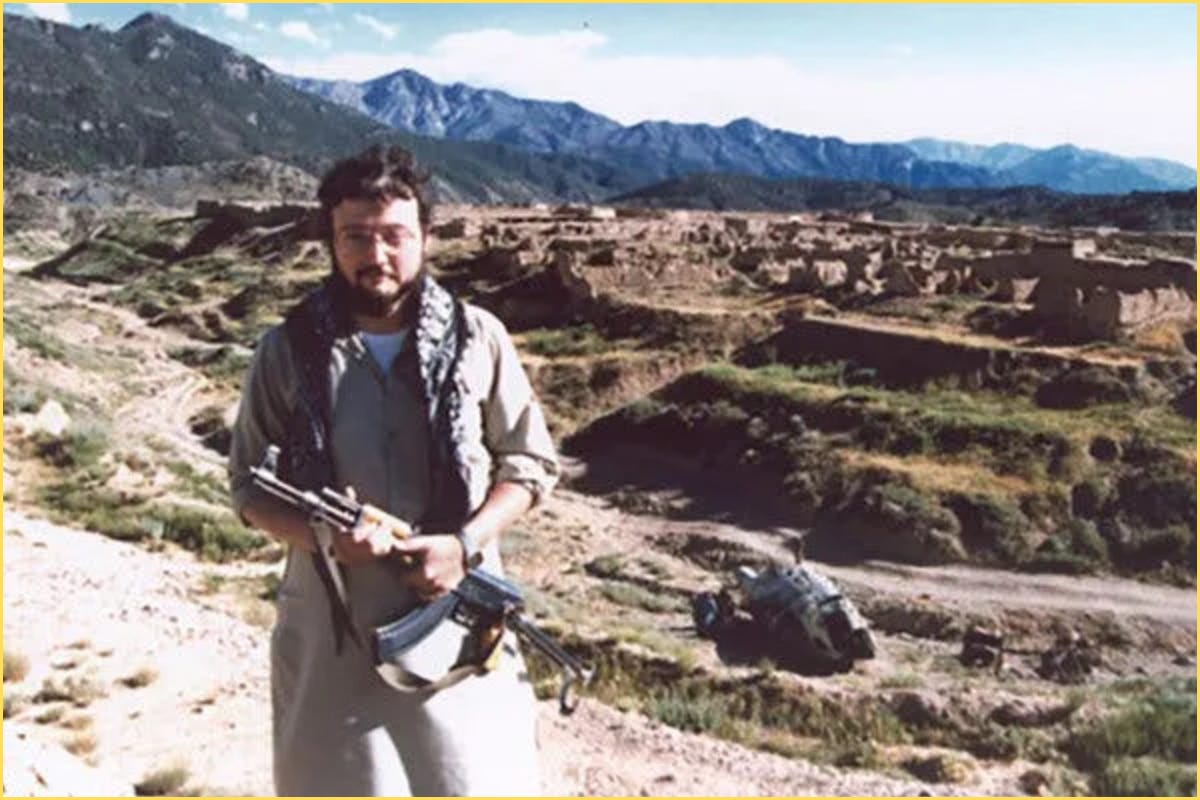

from palace insider to intelligence liability

Jamal Khashoggi, Adnan’s nephew, inherited his uncle’s instinct for navigating power, but wielded it with a subtler, more politically literate touch. He was more than a journalist, he had been an intelligence insider, a conduit between royals and policymakers, and a discreet advisor whose contacts reached from Riyadh to Washington.

Those close to him suspected that, behind his measured op‑eds, he carried sensitive knowledge about MbS and his inner circle, including possible links to the same global web of surveillance, kompromat, and covert deals in which Adnan and Epstein once operated.

By 2018, his columns had grown sharper, questioning MbS’s authoritarian consolidation, the suppression of dissent, and the quiet steps toward normalization with Israel.

When Jamal entered the Saudi consulate in Istanbul in October 2018, ostensibly for marriage documents, he walked into a death trap. The CIA would later assess with high confidence that MbS personally ordered the operation, a rare instance where Langley publicly pointed at a sitting ally, leading some to speculate that the crown prince may have crossed a line or targeted someone of deeper value to U.S. intelligence.

The killing was carried out with chilling precision. There was a hit team flown in on state aircraft, a rapid execution, dismemberment with bone saws, and disposal. The sheer brutality of it all seemed excessive if he were merely an inconvenient columnist. To those who believe he was poised to reveal damaging truths, potentially about kompromat pipelines linking Riyadh to actors like Epstein, or even functioning as a quiet Western asset, the assassination looked less like silencing a critic and more like punishing a breach in the network.

In this reading, Jamal’s fate was about cutting off a line of intelligence that could destabilize the apparatus itself. The act temporarily shattered MbS’s reformist image, but within months, outrage quieted down, global investors returned, and the crown prince’s hold on power became even more untouchable.

connecting the dots

From Adnan Khashoggi’s original blueprint of arms, influence, and covert leverage, to Jeffrey Epstein’s refinement of that model into an alleged Mossad-linked blackmail machine, the chain runs through Mohammed bin Salman’s presence in that world and ends with Jamal Khashoggi, who may have known too much and paid with his life. Each man is a link in a decades-spanning circuit of money, weapons, intelligence, and coercion that moves across borders as effortlessly as guests on a private jet.

The photograph is not definitive proof of a conspiracy, but in the language of power, presence can be the message. It hints that these worlds didn’t just cross paths; they overlapped, and perhaps fed one another.

If Epstein’s network was a foreign intelligence kompromat pipeline, MbS’s appearance inside it could have repercussions that stretch far beyond a single scandal. It could shape Saudi Arabia’s foreign policy, unsettle the kingdom’s internal stability, and erode the Muslim world’s trust in the Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques.

Blackmail in the wrong hands could turn the Abraham Accords from a calculated choice into a coerced act, push Riyadh into positions against its stated principles (if it even has any), or ignite rivalries inside the royal family. In the region, it could disrupt the U.S.–Saudi–Israeli balance, embolden rivals like Iran, and harden public cynicism toward Muslim leadership.

One piece of leverage can dictate terms, override sovereignty, and fracture alliances. Power works in networks, and networks leave traces, sometimes as subtle as a portrait on a wall in a Manhattan mansion.

That trace links four men across decades, continents, and clandestine deals. And in the end, whether the currency is arms, kompromat, diplomacy, or assassination, the rule of this world remains:

Access creates power. Power ensures survival. And survival means someone always keeps the receipts.