how gum arabic helps fuel sudan’s war

sudan supplies most of the world’s gum arabic, and in today’s civil war, that everyday ingredient is feeding both militias and multinationals.

Sudan’s war economy isn’t just about gold. Another commodity, less visible but bound just as tightly into global capitalism, is now underwriting the conflict. Gum Arabic. Which Sudan produces around 70 to 80 percent of the world’s supply.

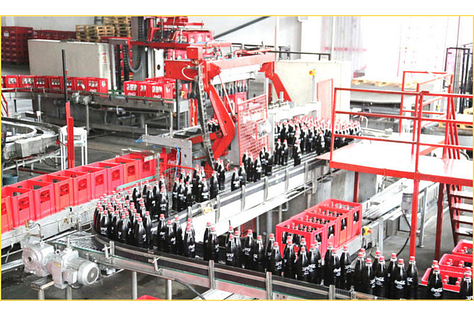

You may not recognize the name, but you’ve consumed it. The sap of acacia trees shows up in everyday life without notice. It keeps sodas like Coca-Cola and Pepsi mixed, holds together M&M’s, adds bulk to pet food, helps lipstick stay smooth, and thickens Danone yogurt. For multinational corporations, uninterrupted access to gum arabic is non‑negotiable. For Sudan’s armed factions, it has become an easy stream of hard currency.

Even at the height of American sanctions in the 1990s, gum arabic was untouchable. Bill Clinton’s administration carved out a special exemption because the U.S. soft drink industry couldn’t survive without it. Sudanese officials knew the leverage they had. One even held up a bottle of Coke in Washington and warned that if gum exports were cut off, the global economy would feel it instantly. Three decades later, the power of gum arabic hasn’t disappeared. It has simply shifted into the hands of militias, most notably the RSF.

Since the civil war erupted in April 2023, the Rapid Support Forces have entrenched themselves in Darfur and Kordofan, the heart of gum production. Farmers and smallholders are forced to pay so‑called protection money just to harvest their own land. Farmers and smallholders are forced to pay protection money just to harvest their own land. Traders trying to move the product eastward are stopped at checkpoints, often paying thousands of dollars per truck. Warehouses are raided, convoys hijacked, stockpiles looted. Reports estimate the RSF may earn tens of millions of dollars each month from these fees, and thousands of tons have been looted since the war began.

The army takes its share as well. The Sudanese Armed Forces control the eastern routes and Port Sudan itself, the country’s commercial lifeline. Nothing leaves without a raft of charges like loading fees, forestry levies, and export duties. A single batch of gum arabic can therefore be taxed twice, once by the RSF in the west and again by the SAF in the east. Both sides profit from the same flow.

When the formal export routes collapse under the strain of extortion and violence, the trade doesn’t stop, it simply goes underground. Gum arabic is trucked west, south and north through rough borderlands into Chad, South Sudan, Egypt, and Libya. Along the way, militias and local officials skim fees, and once the cargo reaches border markets it is relabeled, mixed with smaller domestic harvests, and presented as if it were produced locally. These informal markets operate on cash and speed, with little concern for origin or certification. From there, the gum slips back into official supply chains through ports and traders who export it onward, making it indistinguishable once it enters Europe or Asia. By the time it becomes part of a soda, a sweet, or a cosmetic, there is no longer any visible trace of the militia checkpoints, forced payments, or looted warehouses that shaped its path out of Sudan.

Check out my earlier article in The Africa Review on how the UAE bankrolled the RSF through Sudan’s gold trade:

Western supply still runs through a handful of processors, France’s Nexira and Alland & Robert, the U.S.’s Ingredion/TIC Gums, and Ireland’s Kerry Group, who refine acacia gum for use before it reaches brands

In food and drink, gum arabic keeps sodas mixed, gives candies their shine, helps bind chewing gum, and thickens syrups, dairy products, and plant‑based milks. In pharmaceuticals, it binds tablets and lozenges and helps carry common medicines into forms like cough syrups and vitamins. In cosmetics it thickens and stabilizes products from lipsticks and mascaras to foundations and sprays. It also still appears in inks, watercolors, and some paper and textile finishes.

Despite corporate pledges to “diversify,” large volumes of gum arabic have continued to leave Sudan since the war began. Reporting shows that major processors like Nexira resumed imports after April 2023, even as some shipments were tied to suppliers forced to pay RSF fees. From those plants, the same material is sold on to Coke and Pepsi bottlers, to Danone and other dairy lines, to Mars and a long tail of confectioners, to Nestlé pet‑food brands, and to personal‑care companies from L’Oréal downward. In practical terms, gum arabic touches almost every aisle in a supermarket and a sizable slice of the pharmacy and cosmetics counter. The consumer experiences only the smooth emulsion, the shiny coating, the reliable texture, while the real costs are paid far away, in the places where the sap is shaken loose at gunpoint.

The qualities that make gum arabic valuable to industry, its stability, its invisibility, its irreplaceability, also make it ideal for a war economy. It is lightweight, easy to move across borders, and impossible to trace once refined. It doesn’t draw headlines the way gold does, but it serves the same purpose, a steady stream of foreign currency for men who finance their campaigns through extortion and terror.

Sudan’s acacia groves were once a source of rural survival, sustaining families and local economies. Today they have been reduced to revenue streams controlled and exploited by armed groups. A bottle of Coke or a tube of lipstick may seem trivial in New York, Dubai or Paris, but the supply chains behind them are soaked in extortion and violence. Gold drew headlines, but gum arabic makes the same point in a quieter way: global consumption is directly tied to atrocities taking place far from the polished shelves of Western supermarkets.

Until gum arabic is treated as the conflict commodity it now is, Sudan’s acacia trees will keep being exploited and ordinary people will continue to suffer.