how to rule a country without being there

at 92, paul biya may run again. but his real power has never been presence, it's the system built to function without him.

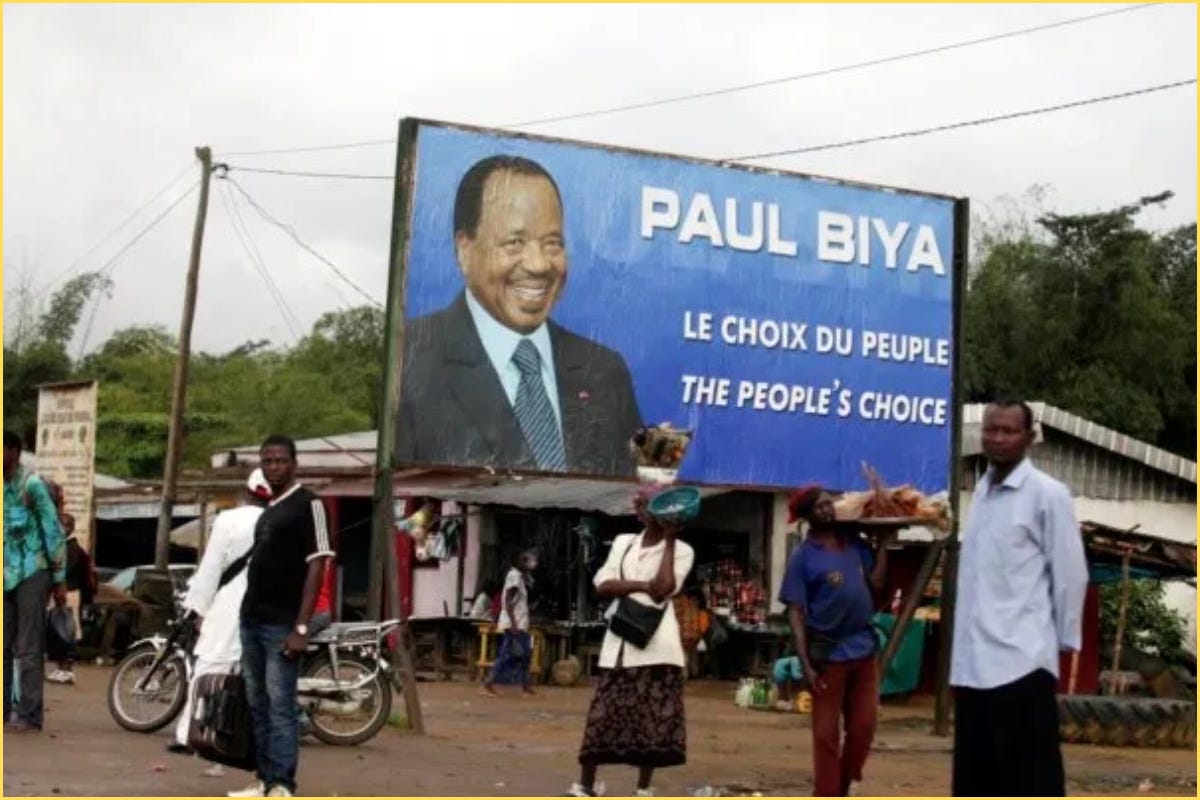

Paul Biya, Cameroon’s 92-year-old president, probably wants to run again. In his 2025 New Year’s address, President Paul Biya expressed gratitude for what he called the “unwavering and massive support” of the Cameroonian people and pledged that his “resolve to serve... remains steadfast.” While he did not explicitly declare his candidacy, the speech was widely interpreted as a signal that he intends to seek an eighth term in the October 2025 elections. His ruling party, the CPDM, is backing him, citing his experience and the need for stability. But critics, including the country’s Catholic bishops, have urged him to step aside, warning that his continued rule risks deepening a crisis of legitimacy.

Biya has long ceased to govern in any meaningful sense, yet remains the unmovable centerpiece of a system designed to endure without leadership. The U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit in December 2022 made that reality uncomfortably visible. On a global stage meant to showcase partnership and African leadership, Biya shuffled in, visibly confused, muttering to aides, "Who are these people present? Why? I didn’t ask for this... Are there important personalities among them?" before being prompted to speak. The moment, caught on a hot mic and punctuated by an audible fart, went viral not just for its absurdity, but because it confirmed what Cameroonians already knew: the president is no longer present in any real way. The summit didn’t just humiliate Biya (and Cameroon and Africa). It exposed the empty theater of international diplomacy that still treats him as a legitimate head of state. It was less an embarrassment than a diagnosis, a symptom of a regime where power persists, even as the man supposedly wielding it fades away.

Biya has ruled Cameroon since 1982. But for years, he has lived mostly in a luxury Geneva hotel. His physical presence in the country is rare; his public appearances, rarer. His rule, though, remains firm. This is not decadence. It is design. Cameroon is not uniquely broken. It is functioning as intended: a Franco-imperial architecture retrofitted by neoliberalism to deliver resources, not rights. The state exists not to govern but to contain; not to serve citizens, but to serve capital and its custodians.

In 2022, French President Emmanuel Macron described Cameroon as a "strategic and stable partner" , a phrase echoed by European and U.S. officials despite mounting repression and conflict. What that means in practice is clear: repression is orderly, corruption is predictable, and foreign access to resources remains unthreatened. Behind the illusion of calm lies a state gutted by elite patronage, militarized rule, and international complicity.

For most Cameroonians, the crisis isn’t war, it’s the daily violence of a state that extracts without providing. Over 23% live on less than $2.15 a day, a figure that has remained stagnant while the number in extreme poverty is growing from 6.3 million in 2021 to a projected 7 million by 2027.

The material conditions speak for themselves. In rural areas, roads vanish with the rains, schools turn into shelters, and clinics operate without doctors, medicine, or electricity. Patients travel hours for care, only to be met with no medicine or informal fees.

Urban life is marginally better but just as precarious. Paved roads crumble, power cuts are routine, and hospitals are overcrowded and underfunded. Public schools are packed, teachers often go months unpaid, and higher education is effectively paywalled. Class determines access.

Survival hinges on the informal economy: in cities, through constant hustle and bribes; in the countryside, through remittances or the whim of local elites. Whether in Douala, Yaoundé or the hinterlands, the pattern is the same: the state is present to extract, absent to serve. More than 60% of Cameroonians were born after Paul Biya took power in 1982, they’ve never known another head of state. Official growth statistics, crafted to soothe donors, obscure the truth: there was never real opportunity, only endurance.

That endurance has limits. In 2024, over 9,000 Cameroonians immigrated to Quebec alone, a 42% increase from the previous year. France remains the top destination: official figures show over 66,000 Cameroonian nationals currently hold residence permits there, but when including naturalized citizens and descendants, estimates place the total Cameroonian-origin population closer to 100,000. This all is contributing to a broader trend that has seen the Cameroonian diaspora around the world more than double since 2010, from under one million to over two million. Among the most famous members of this growing diaspora is Francis Ngannou, a former child laborer who, years earlier, walked across the Sahara, crossed the Mediterranean, and lived homeless in Paris before becoming a world champion UFC fighter. His story is often framed as triumph. It’s also indictment.

Biya’s longevity is remarkable only in duration. Like his peers in Equatorial Guinea and Congo-Brazzaville, he has ruled through constitutional manipulation, ethnic balancing, and an iron-fisted security apparatus. But unlike other strongmen, Biya does not rule through charisma or omnipresence. He rules through absence. His speeches are rare, his decisions outsourced to a loyalist circle. The most common phrase on official documents is “high instructions from the president”, issued in his name, not by him. What protects him is not presence, but a fortified architecture of fear and patronage (including a carefully managed military, well-paid loyalists, and constant reshuffling to prevent dissent).

Power in Cameroon flows from a vacuum. And that vacuum is profitable, for Biya and his clan, for international investors, and for the foreign states that underwrite it.

Corruption is not incidental. It is foundational. For over four decades, billions have vanished through embezzlement, inflated contracts, and ghost projects. From oil to public works to defense, corruption is not merely tolerated, it is organized. In 2023 alone, Cameroon’s official anti-corruption watchdog, the National Anti-Corruption Commission (CONAC), reported over $188 million lost to graft, a staggering figure made more alarming by the fact that it reflects only documented cases. If that’s what the government admits, the real number is likely far higher. Even more audacious was the alleged theft of billions of CFA francs earmarked for hosting the Africa Cup of Nations, a scandal so large it led to Cameroon losing hosting rights in 2019, with the tournament delayed and relocated. Ministers are jailed selectively, not for accountability but for political signaling. Former Water and Energy Minister Basile Atangana Kouna, extradited from Nigeria and convicted in 2021 for embezzling public funds, later had his charges dropped by presidential order. A move that underscored the political nature of Cameroon’s so-called anti-corruption campaign. The Special Criminal Court, which prosecuted him, operates not like a judicial body, but a presidential instrument: a tool to discipline rivals, reclaim stolen funds selectively, and project reform to international donors while shielding loyalists. His case, like others before it, revealed how justice in Cameroon often bends to political expedience rather than principle. Last month, a player on Cameroon’s national football team alleged they were asked to pay bribes to make the World Cup squad (a bitter irony, given Biya’s carefully cultivated image as the team’s "number one supporter", using football victories to distract from governance failures and bolster national pride, even while corruption festers within the sport itself). The Speaker of the National Assembly, Cavaye Yeguie Djibril, made headlines after 85 million CFA francs were stolen from his home, raising questions about why such sums were stored there at all. These are not isolated incidents. They lay bare a political economy where impunity is policy. Luxury cars and lavish weddings make headlines while hospitals run out of gloves. Asset seizures are announced with fanfare and reversed quietly. The image of accountability is preserved just enough to appease donors, reassure loyalists, pacify opportunists, and convince a portion of the public, some too desperate, some too isolated, that this is what development looks like. Meanwhile, the machinery of plunder grinds on, uninterrupted and institutionalized. Corruption is not a bug in the system, it's the software. The operating principle. In Cameroon, the state doesn't malfunction when elites and foreign companies/countries loot; it performs exactly as intended.

Meanwhile, Cameroon’s crises are deepening. In the Far North, Boko Haram and Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) have intensified a cross-border insurgency fueled by poverty and state neglect. In 2024 alone, over 700 violent incidents led to nearly 800 deaths. In the Anglophone regions, what began as a peaceful protest movement in 2016 has hardened into a brutal conflict. Civilians are trapped between a repressive state and separatist militias that increasingly mirror its violence. As of now in just this conflict, more than 6,500 have been killed, over 580,000 displaced internally, and around 76,000 forced to flee to Nigeria.

Cameroon’s borders, drawn by colonial masters, remain open wounds. In the East and North, fighters and bandits from the Central African Republic and Chad cross with ease. Boko Haram and ISWAP exploits a similar vacuum in the Far North’s Lake Chad basin. The absurdity is geographic just as much political: in the Far North, nomadic Arab and Fulani communities navigate a Sahelian belt plagued by insecurity and drought; in the deep South, Cameroon shares dense rainforests and enduring ethnic ties with Congo, Gabon and Equatorial Guinea. These extremes, desert margins and equatorial jungle, are yoked together by a colonial cartography that made no room for cohesion, only control.

Nowhere is the afterlife of colonialism more explosive than in Cameroon’s Anglophone regions, where the fight is not just about English vs French. What began in 2016 as a legal and educational protest has hardened into a war fueled by decades of structural exclusion. The Francophone-dominated regime, anchored in Biya’s Beti-Bulu inner circle, has sidelined Anglophone communities from political power, economic opportunity, and the institutions that shape public life. The conflict speaks in colonial tongues, but its drivers are postcolonial: the dismantling of federalism, the centralization of power, and the violent repression of dissent. The government’s refusal to negotiate a real political settlement is not born of confusion or incapacity. It is policy, a policy designed to preserve centralized control, avoid legitimizing separatist demands, and sustain a militarized status quo that serves the ruling elite.

The violence is not symmetrical. The Cameroonian state, trained and armed by foreign powers, including the United States and Israel, deploys collective punishment as policy. These are the self-proclaimed “most self-righteous defenders of democracy” on the global stage, yet both assist another regime that jails journalists, razes villages, and criminalizes dissent (as usual). This isn’t a contradiction, it’s how empire works. Biya is not an outlier, but a product. Washington and Tel Aviv don’t support him despite the repression; they support him because his repression keeps things in place.

France calls Cameroon a “strategic partner.” Strategic for whom? French corporations still dominate Cameroon’s ports, telecoms, oil terminals. Its still colonization but now dressed up in contracts and diplomacy. The CFA franc, backed and controlled from Paris, locks Cameroon into a monetary order it never chose. French firms run key parts of the economy. This isn’t a partnership. It’s management, designed to keep the old colonial system running smoothly.

The IMF and World Bank demand austerity in the name of reform, while shielding the very elites who loot the state. China builds roads and ports not out of solidarity but strategy. Whether the regime is democratic or despotic doesn’t matter to them. What matters is access to contracts, markets, leverage.

Even Russia has joined in. Through media outfits like Afrique Média, it amplifies pro-Kremlin, anti-Western narratives not to support Biya directly, but to weaken French influence. Yet in doing so, it props up the same system. This also isn’t solidarity, it’s opportunism. Russia, like its rivals, is in Africa not to dismantle imperial legacies, but to carve out its own sphere of influence, using anti-colonial rhetoric while sustaining the extractive status quo.

Each power says one thing and does another. Each one claims to promote freedom and economic development and each one depends on regimes that crush it or leaves out the many. Biya may be brutal, but he offers something more precious to foreign capital: predictability.

The regime persists because it is useful. Cameroon’s elite occupy fortified mansions, vacation in Europe, and profit from monopolized contracts and foreign partnerships. Baba Ahmadou Danpullo, the country's wealthiest individual, boasts a net worth of approximately $940 million, amassed through ventures in real estate, telecommunications, and agriculture . Paul Fokam Kammogne, founder of Afriland First Bank, commands a banking empire with assets across multiple African nations . Kate Fotso, CEO of Telcar Cocoa, oversees 30% of Cameroon’s cocoa exports, solidifying her status as the nation's richest woman with an estimated net worth of $252 million . Collectively, their fortunes eclipse those of millions of Cameroonians. These vast accumulations of wealth are the result of a system meticulously designed to concentrate wealth and power. The Cameroonian state, through its policies and alliances, functions to safeguard and perpetuate this economic hierarchy

But the model is cracking. Across Africa, people, especially the young are rejecting the bargain of repression and economic dispossession for the illusion of order. From Kenya’s youth-led anti-tax protests to opposition marches in Uganda and online organizing in Nigeria, signs of dissent are spreading. Across the continent, rebellions are emerging against regimes seen as corrupt, complicit, or colonial. Not just for their repression, but for enabling foreign powers and local elites to siphon off wealth while most citizens struggle. Still, these movements are in their infancy. The elites who control African states are deeply entrenched, shielded by decades of patronage, surveillance, and foreign sponsorship. They preserve their dominance not just through force, but through keeping schools underfunded, public awareness low, and inequality high. Education is deliberately underfunded to keep people uninformed and easier to control. Unlike other continents, the path to political transformation here is obstructed at nearly every level. Cameroon hasn’t reached the point of open upheaval, but pressure is building. Youth-led protests remain rare due to repression, but civic engagement is growing, from mass voter registration drives to digital dissent. Abroad, the diaspora is louder and bolder, organizing across borders to confront a regime that has long refused to listen at home. And even within the elite, Biya’s long absences and looming mortality are provoking anxiety about what, or who, comes next.

Biya may no longer reside in Cameroon. But the system he built still does. Guarding power, suppressing dissent, and extracting value. The opposition is fragmented. Maurice Kamto leads a coalition, but unity remains elusive. Other figures, like Cabral Libii and Akere Muna, are running separately, fracturing the vote. The divisions are not just personal or strategic, but also ideological and ethnic, shaped by a colonial legacy that forced disparate regions and groups into a single state. Kamto draws much of his support from the Bamiléké people in the West. Cabral Libii, despite sharing the Beti/Bulu ethnic background with President Biya, has tried to court youth and reform-minded voters, particularly in the Center and South. Akere Muna, from the Anglophone Northwest, appeals to frustrations in the English-speaking regions. In Cameroon, political allegiance often aligns with regional and ethnic lines, making opposition unity fragile, not only because of ego or ideology, but because the political terrain itself was designed to divide. And even a united front would face rigged odds: the electoral commission, judiciary, and media are all instruments of the regime. In Cameroon, elections are more like coronations, choreographed to preserve the status quo.

Even Biya’s likely successors offer no break with the past. Senate President Marcel Niat Njifenji, the constitutional heir, is 91. Franck Biya, the president's son, is floated as the dynastic fallback. Ferdinand Ngoh Ngoh, the powerful Secretary-General at the Presidency, is also rumored as a contender. He is a figure who has signed off on presidential decisions for years and been described as the regime’s de facto enforcer. One offers senescence. Another, inheritance. The third, continuity without accountability. None offer change.

The real question isn’t whether Biya will run in 2025. It’s whether the system he hardened over four decades, built on his absence, enforced by loyalists, and insulated by foreign backers, will crumble or simply continue under new management. At 92, Biya is unlikely to finish another term. But that hardly matters. The deeper question is whether his death will trigger change, or will it be merely a reboot.

After 42 years, the reckoning isn’t hypothetical. It’s coming. What follows is uncertain, except for one thing:: the foreign powers and local elites who propped him up will scramble to preserve the system. Not because it’s viable, but because it reliably serves their interests. It delivers what they need, no matter the cost to Cameroonians.