india is dismantling the world’s most successful water treaty

by treating the indus as leverage, not a lifeline. new delhi is redefining what upstream powers can get away with.

On April 23, India fractured the world’s most durable water pact.

A day after insurgents killed 26 civilians in Kashmir, New Delhi suspended its participation in the Indus Waters Treaty. This means halting data sharing, withdrawing from the Permanent Indus Commission, and signaling a reassessment of its treaty obligations to Pakistan. The move marked not just a bilateral rupture, but a potential unraveling of the planet’s most resilient model of water diplomacy.

The Indus Waters Treaty, brokered by the World Bank in 1960, divided the vast river system between India and Pakistan. It was a Cold War anomaly: a technocratic workaround for a geopolitical standoff. Even as the two countries went to war, the water kept flowing, not because of goodwill, but because the treaty treated water as infrastructure, not ideology.

That firewall may be eroding.

India has not formally withdrawn from the Indus Waters Treaty, but its recent suspension of participation marks a significant shift in its approach to the agreement. In recent weeks, senior Indian officials have framed the river system as strategic leverage. Public statements suggest India may reinterpret the treaty’s constraints, exploit its ambiguities, and test its limits. Not quietly, but pointedly.

That shift matters far beyond South Asia. It cracks the norm that upstream powers restrain themselves for the sake of downstream stability. If India moves first, others may follow.

China has long held strategic control over the Mekong River, affecting water access in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Thailand. Drawing criticism for dam-building that disrupts regional ecosystems and livelihoods. In Africa, Ethiopia’s Grand Renaissance Dam on the Blue Nile has alarmed Egypt, which depends on the river for 90% of its freshwater. And in Central Asia, tensions flare periodically over water control between Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, especially in drought years.

These aren't theoretical parallels. They’re live tests of the same question: Can a treaty or norm hold when an upstream power decides it no longer serves its interests?

how india could squeeze the flow

India can’t turn off the Indus. But it doesn’t have to. The Indus Waters Treaty grants India limited rights over the western rivers, the Chenab, Jhelum, and Indus proper, including the ability to build run-of-the-river hydroelectric projects that do not significantly alter the total volume of water. Now, Indian officials are openly discussing ways to push those limits.

Among the options in circulation:

accelerate dams

India has already constructed upstream dams like Baglihar and Kishanganga. Following the suspension of the treaty, India has expedited the construction timelines of four hydroelectric projects in Kashmir, Pakal Dul (1,000 MW), Kiru (624 MW), Kwar (540 MW), and Ratle (850 MW), all located on the Chenab River. These projects are now slated to be completed ahead of schedule between 2026 and 2028, potentially allowing India to delay flows during critical planting windows in Pakistan.

manipulate timing

India has commenced reservoir flushing, the sudden release of water to clear sediment from dam reservoirs, at the Salal and Baglihar dams without prior notification to Pakistan, a departure from past protocol under the treaty. While technically permissible, the uncoordinated timing of these releases signals a more assertive posture. If conducted during monsoon season, such surges could overwhelm downstream defenses and exacerbate flooding in Pakistan.

reduce flow

India has significantly reduced the flow of water through the Baglihar Dam on the Chenab River, with reports indicating a 90% drop in water supply to Pakistan. Similar measures are being considered at the Kishanganga Dam on the Jhelum River.

These aren’t covert strategies. Indian officials have described them as deterrents, retaliatory tools rather than cooperative mechanisms. The language has shifted: from what’s allowed to what’s deserved.

the cost to pakistan

Pakistan lives and dies by the Indus. Nearly 80% of its cultivated land, about 16 million hectares, depends on the river system for irrigation. Wheat, rice, sugarcane, cotton: these aren’t just crops; they’re the foundation of the country’s food supply and export economy.

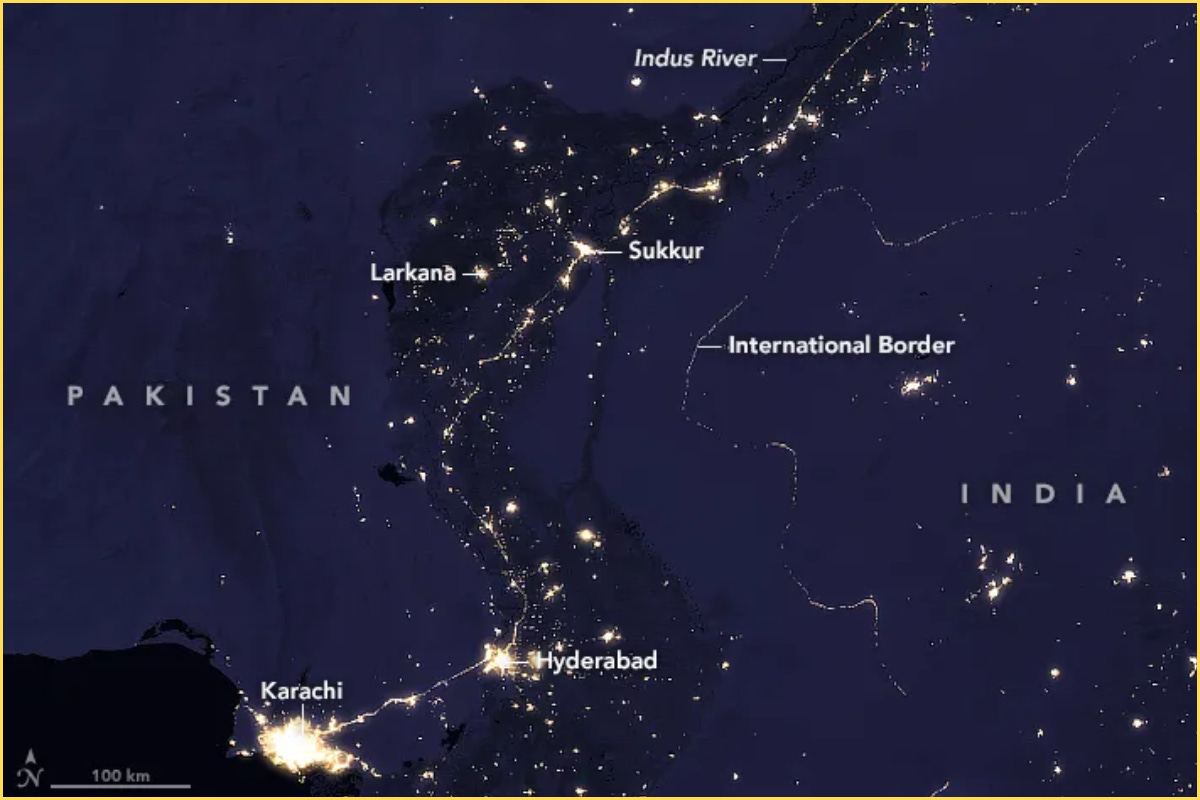

Major cities like Lahore and Multan draw directly from the Indus and its tributaries for drinking water and sanitation. Even Karachi, far downstream, relies on Indus-fed conveyance. As urban populations swell and aquifers sink, the pressure on surface flows intensifies.

Tarbela and Mangla, the country’s two largest dams, typically supply nearly a third of Pakistan’s electricity. But as of May 2025, both are nearing dead storage. Tarbela has already shut down most of its power units. Mangla’s levels are just above the red line. The causes are layered. Climate volatility, sedimentation, and now, upstream manipulation.

This crisis is no longer hypothetical. Per capita water availability has dropped to around 860 cubic meters a year, below the scarcity threshold and falling. Any sudden disruption upstream, even if technically legal, could push the system into collapse: failed harvests, blackouts, price shocks. In water-stressed provinces like Sindh and Punjab, unrest wouldn’t be a risk. It would be what happens next.