kenya’s corridor of complicity

what ruto calls diplomacy is funding a militia and empowering its foreign sponsor.

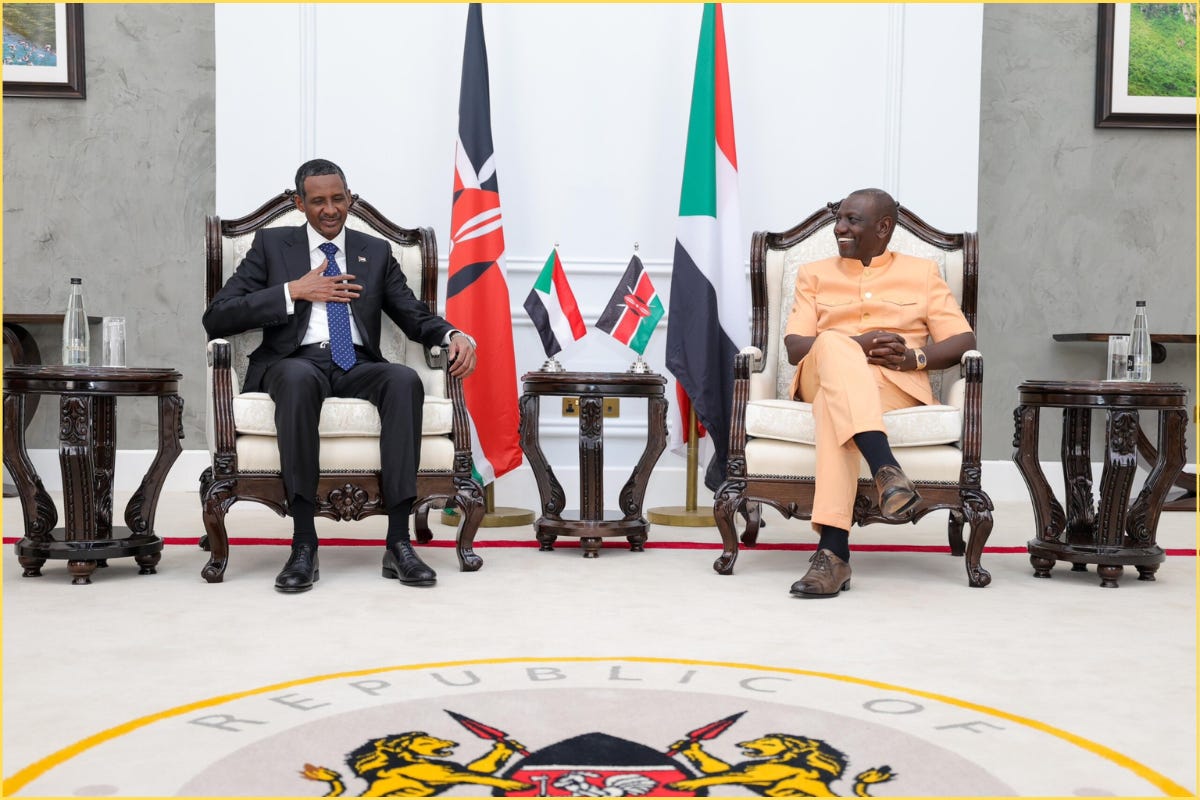

President William Ruto is selling his Sudan policy as peace diplomacy. But Kenya’s embrace of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), the militia accused of genocide in Darfur, has less to do with peace and more to do with gold, gulf money, and geopolitical ambition.

New revelations suggest that Ruto’s ties to RSF commander Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, known as Hemedti, are greased not just by diplomacy but by a covert trade network linking Sudanese gold to Dubai, via Nairobi. At the heart of it is a three-way alliance: Sudan’s most brutal warlord, Kenya’s opportunistic pivot, and the United Arab Emirates, eager to bankroll its proxy.

In April, former deputy president Rigathi Gachagua publicly accused Ruto of facilitating gold laundering for RSF commander Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, known as Hemedti. “He is helping them clean their gold money through our country,” Gachagua told KTN News, claiming Sudanese gold was being routed through Nairobi to Dubai. He alleged that in 2023, Ruto pressured him to extend an official invitation to Hemedti and that his signature was later forged to issue a second one.

The allegation fits a well-documented pattern. The RSF controls key mining areas in Darfur and Kordofan and has long relied on gold exports to finance its war against Sudan’s army. In January 2024, the U.S. Treasury sanctioned multiple entities, including AZ Gold and several UAE-based firms for purchasing RSF-linked gold and channeling profits through networks tied to Hemedti’s family and business associates.

The UAE’s role is neither covert nor new. UN reports have repeatedly identified it as the RSF’s principal sponsor, arming the militia, funding its operations, and giving safe passage to its gold. Now, it’s deepening its hold on Nairobi.

Before we go further, here’s a piece I wrote for The Africa Review that lays out the UAE’s role in Sudan’s war in full:

In January, President Ruto traveled to Abu Dhabi to finalize two major agreements: a $1.5 billion commercial loan to help finance Kenya’s budget, and a Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement, the first of its kind signed by the UAE with a continental African country. While the UAE had earlier struck a similar deal with Mauritius, Kenya’s agreement marks a strategic expansion onto the African mainland, positioning Nairobi as a regional gateway and reinforcing the UAE’s ambitions as a global logistics and finance hub.

The UAE, which is already Kenya’s second-largest source of imports and third overall trading partner, is also positioning itself as a key investor in the country’s stalled infrastructure projects, including rail and energy. These moves are not just economic. They mark the consolidation of a new political and financial axis: RSF gold, Emirati capital, and Kenyan diplomatic cover.

In February, Kenya hosted a summit in Nairobi where RSF officials and rebel groups signed a charter forming a rival Sudanese government. Sudan’s recognized authorities in Port Sudan were excluded. Days later, RSF fighters massacred more than 200 civilians in White Nile state. Khartoum responded by recalling its ambassador and banning Kenyan tea imports.

Kenya’s foreign ministry insists it was promoting dialogue. But no amount of spin can change the optics of Abdul Rahim Dagalo, Hemedti’s brother, raising a fist under Ruto’s portrait while civilians were being buried in mass graves.

Kenya once positioned itself as a champion of Pan-African solidarity. It hosted liberation leaders, backed regional peace efforts, and helped found the Organization of African Unity on the promise of African sovereignty and non-interference. That legacy sits uneasily beside its emerging alignment with a paramilitary force seeking to topple a recognized African government, enabled by a foreign power with ambitions that extend far beyond trade. Kenya’s support for the RSF isn’t neutrality, it’s complicity. And in aligning itself with a foreign-backed militia, it has traded Pan-African principle for transactional politics.

On May 8th, Kenya signed seven more bilateral agreements with the United Arab Emirates, ranging from defense cooperation to transport infrastructure. Officially, these deals promise economic development. But taken alongside Kenya’s quiet endorsement of the RSF, they suggest something more consequential: a willingness to trade moral leadership for financial leverage and to enter an unequal partnership likely to demand costly concessions down the line. By deepening dependency on a foreign power with a history of coercive diplomacy in Africa, Kenya risks not just complicity, but vulnerability.

The UAE’s playbook in Africa is well-established. Across the continent, it has armed militias and separatists, backed coups and autocrats, and used infrastructure deals to entrench its influence. What began as strategic engagement often ends in political dependency or fractured sovereignty. Its latest foothold is Nairobi.

This is not peace diplomacy. It is a new kind of alignment, one where power flows not through alliances of principle, but through corridors of extraction. And Kenya, once a moral center, is becoming a logistical one.