tanzania’s crackdown has a feminist face

once hailed as a break from the ruling party's authoritarian playbook. tanzania’s president is now jailing opponents, torturing activists, and banning rivals from elections. the mask is off.

Last month, Kenyan activist and photojournalist Boniface Mwangi and Ugandan lawyer and journalist Agather Atuhaire were arrested in Dar es Salaam. Where they had traveled to attend the court hearing of Tanzanian opposition leader Tundu Lissu. According to their public testimonies, they were abducted from their hotel, blindfolded, interrogated, and then sexually assaulted and tortured by Tanzanian security officers. Mwangi, who spoke at a press conference in Nairobi, said he was hung upside down, beaten, and sodomized with objects while his attackers filmed the abuse and forced him to say 'Asante’ (thank you in Kiswahili) to President Samia, a cruel gesture meant to mock and humiliate him. Atuhaire said she was raped. Both were later dumped near their respective borders and forced to leave the country.

Their stories, as harrowing as they are, are not isolated incidents of regional overreach or border violence. They represent a new and dangerous regional trend: the externalization of repression. Tanzania is no longer only targeting its own dissidents, it is sending a clear warning to others in East Africa: solidarity will be punished.

the fall of a reformist illusion

Just over two years ago, U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris stood beside Tanzania’s first female president, Samia Suluhu Hassan, calling her a "champion of democratic reform." Samia had lifted bans on opposition rallies, released political prisoners, and repealed draconian media laws. After the death of John Magufuli, an autocrat, many believed a new era had dawned in East Africa.

But as the country prepares for its October 2025 general elections, the script has flipped. The opposition is either banned, imprisoned, or dead. Tanzania has descended into a familiar autocratic rhythm. And Samia Suluhu Hassan is no longer pretending otherwise.

The arrest of opposition leader Tundu Lissu on fabricated treason charges marked a turning point. A vocal critic of electoral rigging and police brutality, Lissu now faces a possible death sentence. His party, CHADEMA, has been barred from participating in elections until 2030. What little remained of Tanzania's democratic process has been quietly buried.

And the repression is not confined to Tanzanian citizens. Increasingly, East African regimes are working in quiet coordination to suppress dissent across borders. Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania, despite their public differences, have shown a pattern of cooperation in repression. Ugandan opposition leader Kizza Besigye was abducted by Ugandan agents in Nairobi. Tanzanian journalist Maria Sarungi was nearly deported back to Tanzania after being arrested in Kenya. Kenyan activists visiting Tanzania have been tortured and expelled. These governments may differ in style, but in practice, they are aligned on one point: silencing dissent is a regional affair. That same impulse is only growing stronger at home.

In Uganda, opposition leader Bobi Wine reported that his bodyguard, Eddie Mutwe, was abducted by security forces loyal to General Muhoozi Kainerugaba, the president’s son and presumed successor. In a series of disturbing social media posts, Kainerugaba openly boasted about detaining Mutwe in his basement, claiming to have shaved his head and beaten him. When Mutwe was later brought to court, observers noted visible signs of torture. Uganda’s justice minister condemned the treatment, but no action was taken against Kainerugaba, underscoring the impunity with which power is exercised in Uganda today.

In Kenya, state violence against dissent has escalated in recent years, particularly during opposition-led protests. Police have been widely accused of using live ammunition, tear gas, and arbitrary arrests to quell demonstrations. Human rights groups also documented violence against civil society actors and journalists covering these protests have also reported harassment and detention.

In Rwanda, opposition voices remain tightly controlled, with critics of the ruling Rwandan Patriotic Front often facing imprisonment, forced disappearances, or exile. The death of activist Kizito Mihigo in police custody and the treatment of political challenger Victoire Ingabire, who served eight years in prison and remains barred from political participation, remains emblematic of the country's zero-tolerance stance on dissent. Beyond its borders, Rwanda has also become a leading force in transnational repression, targeting dissidents abroad through abductions, digital surveillance, and even assassinations. The 2020 abduction of Paul Rusesabagina (the guy from Hotel Rwanda) from Dubai, widely condemned as a state-sponsored rendition, and the unsolved 2014 murder of exiled former intelligence chief Patrick Karegeya in Johannesburg, highlight the lengths to which Kigali will go to silence opposition.

Burundi’s opposition was largely sidelined in advance of the June 5 parliamentary elections. The main opposition party was suspended in 2023, and new laws barred former leaders from running under other banners or as independents. With the strongest challengers removed from the political landscape, the ruling CNDD–FDD faced little meaningful competition.

Check out this article from The Plantain to learn more about Burundi and the recent elections there:

Across the East African Community, autocrats are tightening their grip on power. Freedom House currently classifies none of the eight EAC countries as fully free. Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, and Burundi are all ranked "Not Free," while Kenya retains a "Partly Free" status despite growing police brutality, protest crackdowns, and surveillance of opposition movements. The average freedom score for the region has plummeted to just 31.2 out of 100. In contrast, countries like Botswana and Namibia, just south of the region, are among the few in Africa still considered "Free," with relatively strong institutions, independent judiciaries, and legal protections for civil liberties. Yet even these democracies highlight a deeper contradiction: both Namibia and Botswana are also among the most unequal societies globally, with Gini coefficients exceeding 53. Political rights may exist on paper, but economic inequality continues to shape access to justice, opportunity, and voice. In Africa, there is often no reliable tradeoff between freedom and prosperity. Gulf monarchies deliver material wealth while denying political rights. In much of the West, civil liberties coexist with broad but uneven prosperity, ranging from robust welfare states to economies offering stability but little mobility. China offers no political rights, yet provides measurable upward mobility and a powerful sense of national pride, anchored in the 'China Dream' and reinforced by state-controlled narratives. Namibia and Botswana uphold political freedoms, but persistent inequality and limited economic mobility leave most people excluded from those gains. In East Africa, by contrast, most citizens are denied both political voice and economic dignity, left without rights, mobility, prosperity, or pride.

And yet, this wasn’t always inevitable. Samia once declared her commitment to the "Four Rs": reconciliation, resilience, reform, and rebuilding. She released CHADEMA leader Freeman Mbowe from prison. She held televised meetings with Tundu Lissu. She promised to open civic space and took steps to reverse some of the worst excesses of her predecessor's rule.

But by mid-2024, that trajectory had collapsed. In August, more than 500 CHADEMA supporters, including Lissu and Mbowe, were arrested ahead of a planned youth rally. In September, CHADEMA official Ally Kibao was abducted while traveling on a bus and later found dead, his body showing signs of severe beating and acid burns. In October, another party leader, Aisha Machano, was kidnapped, assaulted, and left injured in a forest. What followed marked a clear return to the violent tactics that defined the Magufuli years. By the end of the year, dozens of CHADEMA members were either behind bars, or disqualified from running. Effectively neutralizing the party ahead of the 2024 local elections, which CCM won handily after most challengers were banned or disqualified (99% of the vote, because why settle for subtlety).

As the October 2025 general election approached, CHADEMA initially called for a boycott under the slogan "No Reforms, No Election." The government's response was swift. Lissu was arrested and charged with treason. Shortly after, the electoral commission disqualified CHADEMA from the election altogether, citing procedural violations, effectively banning the main opposition from Tanzanian politics until 2030. Lissu remains in prison, having appeared in person at a May 19 court hearing where he raised his fist in defiance as supporters chanted “No reforms, no election.” The court adjourned the case to June 2, 2025, citing the need for the prosecution to complete its investigations. The court also ruled that future hearings would be conducted in open court rather than virtually, as Lissu had demanded. The trial is ongoing, with the next hearing scheduled for June 16.

Why did Samia turn back? Some argue she began losing control over her party, prompting a calculated shift. To protect her position ahead of the election, she leaned on Magufuli-era hardliners, abandoning the reformist image that once won her praise and repositioning herself as the candidate of continuity and internal loyalty.

There are signs of this consolidation. In 2024, Samia removed Foreign Minister January Makamba and Information Minister Nape Nnauye, two figures seen as more independent-minded within CCM. In their place, she reinstated Magufuli-era loyalists: Palamagamba Kabudi, who previously held the foreign affairs portfolio, and Damas Ndumaro, a party veteran closely aligned with CCM’s authoritarian legacy. She also tapped William Lukuvi, a hardliner with a populist streak, as her chief political advisor. These moves signaled a decisive return to the repressive machinery of the past. Samia has since tightened control over the judiciary and revived the same anti-foreigner rhetoric once favored by Magufuli. Last month, she vowed to protect Tanzania’s sovereignty from outside meddling. A few days later, Mwangi and Atuhaire were arrested and eventually expelled from the country.

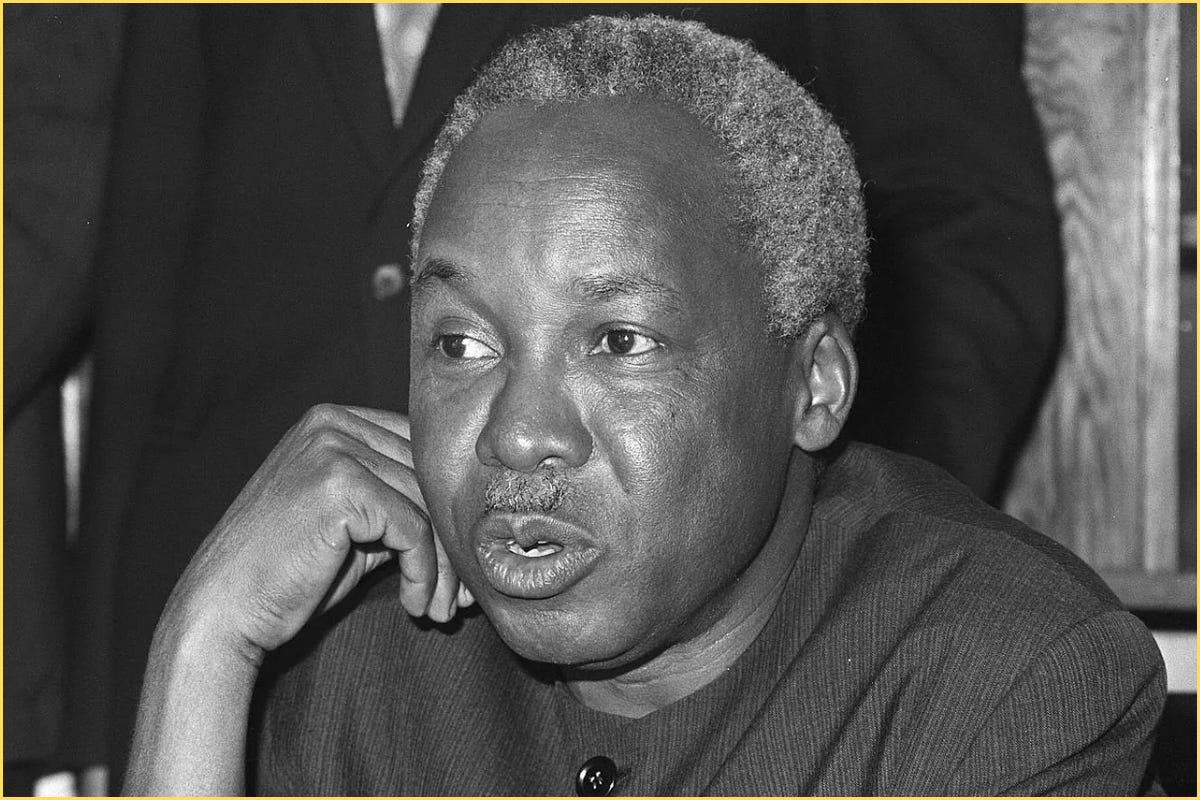

To understand how Samia got here, you have to understand CCM, one of the world’s longest-ruling parties, and the architect of Tanzania’s authoritarian infrastructure. In power continuously since independence in 1961, first as TANU and later as CCM after a 1977 merger, Chama Cha Mapinduzi became the state. Instead of creating institutions that could mediate power, CCM fused itself to the machinery of government. Loyalty mattered more than competence; speaking out was criminalized rather than debated. Even Nyerere’s socialist project, rooted in a vision of self-reliance and collective dignity, sounded noble, and in an alternate world might have worked. But like too many post-independence visions, it was imposed from above, not built from below. The state dictated, the people obeyed. There were no independent institutions to mediate or question power, no real checks, no free press, no civil society allies. Popular participation was assumed, not earned. So when Ujamaa faltered, there was no mechanism for course correction, only bureaucratic insistence and coercion. The promise of equality collapsed under the weight of exclusion. The result wasn’t socialism with Tanzanian characteristics, it was authoritarianism draped in revolutionary language.

After the economic crisis of the 1980s, CCM abandoned its socialist rhetoric and embraced neoliberalism. Structural adjustment programs, introduced under Ali Hassan Mwinyi, dismantled many of the state-led mechanisms Nyerere had built, but without building functional alternatives. The party privatized public assets, slashed social spending, and opened up to foreign capital, but it kept its authoritarian reflexes intact. What replaced Ujamaa wasn’t democratic socialism, it was clientelism underwritten by IMF conditionality. And like many of Africa’s post-independence liberation parties, CCM aged into an elite cartel: leaders trading on liberation credentials while presiding over neoliberal decay. Though Samia Suluhu Hassan is the country’s first female president, she now fronts a system still dominated by aging male elites who were not part of Tanzania’s liberation generation, but routinely invoke its revolutionary legacy to legitimize authoritarian rule.

The result is a political machine that doesn’t need to win people over. It only needs to perform the motions of democracy while entrenching control. The promise isn’t a better life, but the absence of disruption. Citizens are managed, not served. Dissent is framed as instability, and public suffering is normalized as national resilience.

Few illustrate this more than Tundu Lissu. Shot 16 times in 2017, exiled for years, and now imprisoned again under treason charges, Lissu has become both the face of Tanzania’s democratic struggle and the system’s most enduring antagonist. His courtroom defiance, raising a clenched fist, repeating “No reforms, no election”, echoes far beyond the courthouse. The campaign to silence him is about preserving a system that cannot withstand scrutiny, and sees refusal not as a right, but as a threat. What Lissu embodies is not just opposition, but an insistence that this machine cannot be negotiated with, it must be confronted.

anatomy of a crackdown

Tanzania is set to hold elections with little meaningful competition, no press freedom, a compromised judiciary, and shrinking political space. Samia Suluhu Hassan is almost certain to win (probably with 99% of the vote). But that outcome isn’t the result of public will, it’s the consequence of a system built to eliminate alternatives and crush anyone who dares to challenge it.

This isn’t the story of a reformer derailed by circumstance. It’s the story of a leader who made a choice, to consolidate power at the expense of ordinary Tanzanians, who are now left without the any real ability to speak out, mobilize, or resist state power.