the central african link

A rebel supply line, a shattered state, and the international system that profits from keeping it that way.

The war in Sudan is supplied through a transnational pipeline of complicit states and quiet corridors, and the Central African Republic (CAR) is one of them. While Chad is the RSF’s main rear base and South Sudan its financial escape hatch, CAR has quietly emerged as a lesser-known but strategic flank: a borderland where fighters are recruited, arms are discreetly moved, and alliances are traded for leverage.

With the calculated tolerance of President Faustin-Archange Touadéra’s government, CAR has become a willing stopover in the RSF’s war economy. Not the center, but a strategic link.

a border town turned launchpad

In the northeastern corner of CAR, along the border with Sudan’s Darfur region, sits Am Dafok (across from the Sudanese town of Um Dafuq), a dry, remote town flooded with Sudanese refugees fleeing the RSF’s scorched-earth campaigns. It sits in Vakaga Prefecture, a sparsely populated region with just 1.1 people per square kilometer. The low population is not just because of geography, but because the population was decimated by Sudanese slave raids in the 19th century. That legacy of depopulation made it ripe for the kind of extraction and exploitation we see today, not just as a launchpad for war, but for mining too.

Gold and diamonds, in particular, are quiet prizes. UN experts and investigative reports have identified RSF-linked networks operating around mining hubs like Sam Ouandja and Ndah in Haute-Kotto, often with the help of Russian mercenaries and local armed actors. These sites feed a smuggling economy that stretches from northeastern CAR through Sudan, fueling both conflict and profit.

According to a 2024 UN Security Council report, Am Dafok has become part of a “supply chain” used by the RSF for recruitment and logistics. A quiet hub where fighters cross back into Darfur and small arms and fuel move discreetly.

The RSF captured Am Dafok in mid-2023 and turned it into a key hub for cross-border recruitment and logistics, with figures like Habib Hareka and Abdallah al-Jazouli helping coordinate operations

the role of the fprc: from seleka to subcontractor

This pipeline wouldn’t function without local partners, and in CAR, that means the FPRC (Popular Front for the Rebirth of Central Africa). A powerful Seleka offshoot that controls much of Vakaga prefecture.

Originally formed from the remnants of the 2013 Muslim-majority coalition that overthrew President Bozizé, the FPRC now operates like a rebel-administered statelet, collecting taxes, running parallel security forces, and negotiating with anyone who brings guns or gold.

While money and logistics matter, so does identity. The FPRC and RSF both draw heavily from Arabized and Muslim communities spread across CAR, Chad, and Darfur. These cross-border ethnic and social ties, particularly among the Salamat and Baggara, reinforce cooperation. The Runga, while not fully Arab, have in some cases aligned with Arabized political and military actors for strategic reasons.

The leader of the FPRC, Noureddine Adam, an ethnic Runga, was reportedly injured fighting alongside the RSF in Nyala, South Darfur in 2023. A startling example of how CAR’s insurgent politics have merged with Sudan’s war.

But this relationship is not new. Fighters from the Janjaweed and now the RSF have been operating in CAR for a long time. During the 2013 Séléka rebellion, Janjaweed elements even fought alongside Séléka forces in their campaign to oust François Bozizé. That collaboration laid the groundwork for a durable, cross-border alliance rooted in mutual interest: access to land, money, weapons, and shared enemies. Over time, the distinctions between mercenary, rebel, and smuggler have blurred, with Janjaweed and later RSF fighters becoming a familiar presence in CAR’s eastern periphery.

Although the FPRC dominates much of Vakaga, it does not control every strategic point. In Am Dafok area, RSF forces operate alongside Misseriya Arab militias. Nomadic groups native to Sudan and Chad but not to CAR but who have long navigated the borderlands for trade, recruitment, and smuggling.

While the FPRC has collaborated with the RSF elsewhere, especially in recruitment, there is no formal alliance between the FPRC and Misseriya fighters. Their relationship appears to be shaped by opportunism and RSF coordination, rather than shared ideology. Each group retains its own leadership, but all benefit from the RSF’s war economy and logistical networks stretching across the border.

This patchwork of interests, stitched together by geography and war, helps explain how RSF movements persist across the border with minimal resistance. It is not that any one group commands the territory entirely, it’s that each faction has carved out a role in a shared ecosystem that thrives on instability.

This long-standing relationship matters because RSF’s freedom of movement in CAR is far less constrained than in Chad or South Sudan. In Chad, RSF relies on top-level coordination with the Déby regime. It also draws on tribal and paramilitary networks, including allied militias from the Baggara and Ta’isha, (and Zaghawa to some extent) who facilitate cross-border movements, logistics, and recruitment in the eastern provinces. In South Sudan, its presence is indirect. Primarily financial, using the country as a space to launder gold and move cash. The RSF does not maintain a ground force there, nor does it have reliable allied militias to leverage. Unlike Chad or CAR, it cannot mobilize militarily. Its function is purely financial.

Libya remains part of the RSF’s outer logistics ring, a reservoir of weapons and smuggling rather than a direct corridor. Routes through Chad have become more erratic, and most of Libya’s border with Sudan is under SAF control, limiting its utility.

But in northeastern CAR, especially in places like Vakaga and neighboring Haute-Kotto, RSF moves with informal consent, protected by rebel deals and geographic obscurity. Fighters don’t just pass through; they organize, recruit, and resupply with little interference.

the president who lets it happen

President Faustin-Archange Touadéra brands himself as a reformer, the professor turned president is navigating a country still embroiled in low-intensity conflict, relying on UN peacekeepers, foreign mercenaries, and international aid to maintain a fragile hold on power.

He has been in office since 2016, after winning elections organized under international pressure to restore constitutional rule. But nearly a decade later, little has changed beyond the symbolism. For most Central Africans, nothing really has improved. The vast majority still live in poverty, without electricity, clean water, or healthcare. Hunger is common, life expectancy remains among the world’s lowest, and nearly 70% of people lack access to basic services.

Touadéra’s real power lies not in governance but in survival and in presiding over a system that generates significant wealth for those at the top and especially for foreign corporations and coffers. While the state is too weak to deliver services, it is strong enough to extract: from gold mines, aid flows, and foreign security contracts, without giving anything back to the wider population. Survival, in this context, is profitable.

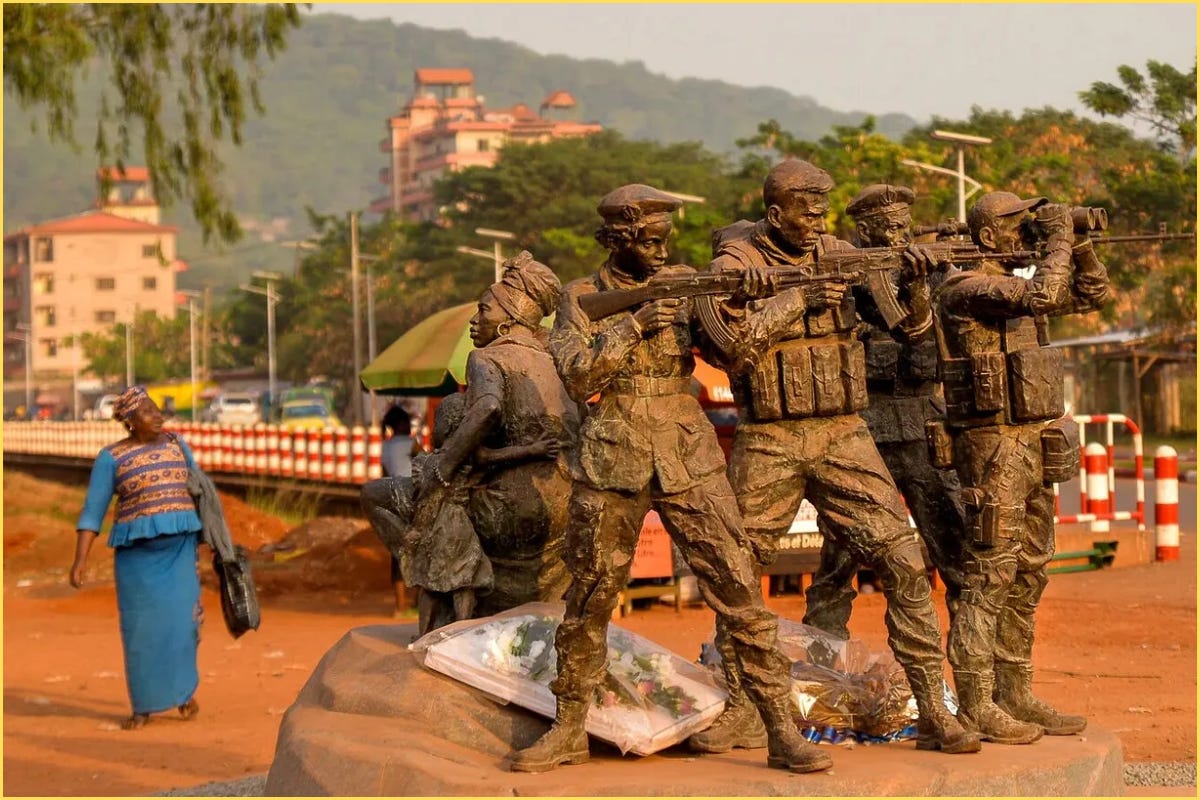

His regime depends on Russian mercenaries, first Wagner, Africa Corps, to secure major cities and protect mineral-rich areas. Russian fighters have helped reinforce government control in places like Birao (capital of Vakaga), where a military base was established in 2022.

But this force projection is selective. Instead of targeting RSF and rebel-controlled areas like Am Dafok or Vakaga’s northern border zones, Africa Corps has focused on securing diamond and gold extraction points and transit routes that feed both government coffers and Moscow’s own resource pipeline.

Rwanda has also carved out a powerful role in CAR’s security architecture. Kigali has deployed troops through both MINUSCA and bilateral deals with Touadéra’s government. While France officially ended its military presence in 2022, Rwanda has filled some of that gap, not as a direct proxy, but as a strategic actor navigating between poles of influence. In several operations, Rwandan troops have operated alongside Russian mercenaries, particularly during the defense of Bangui in 2020–21.

Unlike in Mozambique, where Rwandan troops explicitly protect French and western energy infrastructure, Rwanda’s deployment in CAR is less directly linked to Western corporate interests. Still, its strong ties with France and the U.S., and its reputation as a stabilizing force, suggest that its presence supports more than just local security. In CAR, Rwanda backs the Touadéra government, secures the capital around Bangui, and expands its geopolitical leverage. Kigali’s presence also aligns with Western preferences by helping manage instability and indirectly counterbalance Russian influence.

So basically, the CAR government lacks the capacity or will to challenge rebel or RSF zones. Africa Corps acts as a selective security force. Guarding resources, not confronting risk (much like the French). Most of Rwanda’s troops are concentrated in and around Bangui, where they serve both symbolic and strategic roles in securing the capital and stabilizing the central government. Beyond that, enforcement is patchy. This arrangement benefits Touadéra, Moscow, Kigali, Paris, Rebels, Hemedti: gold and diamonds (and other stuff) flows out, rebels are kept at bay, and the state appears intact while its peripheries are informally outsourced.

In this context, Touadéra’s recent diplomatic shift, distancing himself from Hemedti and aligning more closely with Sudan’s General Burhan, is not really a break of allegiance but rather risk calculation. In late 2024, under international pressure and fearing RSF spillover, Touadéra reportedly urged Sudan to arrest CAR rebels like Noureddine Adam, operating from Sudanese territory. The gesture was read as a signal to Burhan and an attempt to disrupt transnational rebel alliances.

Yet even as Touadéra tries to reposition himself, his government still allows RSF-linked networks to operate across the northeast. Not because it endorses them, but because it lacks the strength or political will to confront them directly.

This isn’t neutrality. It’s strategic indifference, born of weakness, calculation, and a war economy that rewards disengagement. The state avoids what it can’t control and it secures what it can profit from. And in the grey zones between power and vacuum, where rebels, smugglers, and militias converge, it simply watches.

the tragedy of the central african republic

To understand why CAR is so easily used. As a corridor, a proxy zone, a disposable link in other people’s wars or interests. We have to look at the material structures that created it. The Central African Republic is not just weak. It was deliberately engineered that way.

CAR is home to over 80 ethnic groups, hundreds of distinct languages and dialects, and a religious population roughly split between Christians, Muslims, and practitioners of traditional beliefs. These communities were not unified by shared national purpose, they were administratively fused by colonial overlords. The result wasn’t a coherent state, but a loose patchwork of overlapping identities and power vacuums. Which are perfect conditions for fragmentation, rebellion, and foreign manipulation.

Under French colonial rule, CAR was governed through direct domination, not indirect alliances. Paris exerted hard control, extracted raw materials like gold, timber, cotton, labor and invested little in state institutions or intercommunal cohesion. Colonial administrators empowered a narrow elite, while neglecting infrastructure and fostering interethnic competition. The borders were drawn for imperial convenience, not postcolonial stability and the legacy is a political system that still functions more as a zone of resource access than as a nation.

What followed independence in the Central African Republic was not decolonization, it was continuity. A neocolonial order in which sovereignty was largely performative, and real power remained outsourced. Infrastructure was minimal. The economy stayed locked into raw export. The social fabric, already strained by colonial borders and forced labor regimes, was further torn by the scramble for patronage, weapons, and foreign backing. From Bokassa’s brutal monarchy to a revolving door of military strongmen, CAR’s postcolonial rulers inherited and often reproduced, a system designed not for governance, but for extraction. The result is a state where sovereignty is more symbolic than structural, and where each new external partner sustains the same logic of fragmentation. Some in new languages: security, development, investment. Or, more often, the same old one: the gun.

Life for most Central Africans remains brutal and stagnant. The majority lack access to health care, electricity, education, or stable employment. Conflict has become routine and it isn’t only driven by rebel groups. In the northwest of the country, banditry and rural criminal violence remain persistent threats. Loosely organized armed groups routinely ambush travelers, extort local populations, and engage in kidnapping for ransom.

While not always affiliated with larger rebel movements, these groups sometimes overlap or cooperate with other bandit groups and smuggling networks that operate across the borders with Cameroon and Chad. This form of insecurity mirrors broader patterns seen across Central and West Africa, where fragile states, weak institutions, and under-policed frontiers give rise to decentralized, profit-driven violence. It is part of a deeper structural crisis, rooted in questions of land, neglect, resource extraction, economic and general marginalization, and militarized survival.

the emiratis are also here

Then there’s the UAE. In March, Abu Dhabi signed a Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) with the Central African Republic, part of a broader Gulf strategy to formalize influence across Africa. Unlike more opaque bilateral deals in places like Somalia or pre-war Sudan, this CEPA mirrors the UAE’s agreements with Kenya and Mauritius, including extensive tariff reductions and investment incentives. It was officially framed as a development deal aimed at boosting trade in agriculture, infrastructure, and technology. But like most such agreements, the real beneficiaries are foreign investors and political elites, not the populations on the ground.

The UAE’s footprint in CAR goes deeper than trade however. Multiple investigations have uncovered evidence that the UAE has used Wagner’s presence in CAR to smuggle weapons to the RSF. In late 2023, CAR militia fighters reportedly intercepted Wagner-run arms convoys intended for the RSF. Captured mercenaries allegedly confessed to coordination between Wagner, the UAE, and actors inside CAR to supply the RSF

As the RSF continues to lose ground to the Sudanese army, CAR’s recent agreement with the UAE raises serious concerns about how economic partnerships in one country can help fuel violence in another. In the Central African Republic, power is fractured: the central government is weak, and large parts of the country are controlled by rebel groups who survive by taxing and exploiting local resources. In this kind of environment, money talks. If the price is right, officials and warlords alike may look the other way or actively support operations that help keep armed groups like the RSF alive. And it’s not just the RSF. Deals like this may also strengthen groups like the FPRC, which could eventually backfire on the government itself. After all, it was Séléka, which once seized Bangui, and the CPC (of which the FPRC is a major offshoot) that later tried to storm the capital again.

Agreements branded as “development” or “investment” can easily become pipelines for war and extraction, not because of what they claim to do, but because of how and where they operate. In fragile states like CAR, where accountability is weak and profit often trumps principle, these deals risk entrenching the very instability they pretend to solve. And everything will likely continue unchecked, because few are watching, and even fewer truly care what happens in the Central African Republic.

CAR represents everything wrong with the international order: a place where sovereignty is nominal, extraction is normalized, and the people who live there are voiceless in the deals made about their land. Whether it’s French troops, Russian mercenaries, or Gulf-funded contracts, the outcome is the same. A nation outsourced and occupied by capital, guns, and silence.

a corridor, not a core

It’s important not to overstate CAR’s role in the war in Sudan. It isn’t Chad. It isn’t South Sudan. There are no major airfields. No hospitals for wounded RSF fighters. No central bank accounts. But that’s what makes it work. CAR’s function is precisely its quiet utility. A staging ground, a smuggling route, a recruitment site.

In this war economy, every border matters, and every weak state becomes an opportunity. CAR doesn’t have to host the war to be part of it. It just has to open the door.

The story of Sudan’s war is often told through its visible actors: Hemedti, Burhan, the RSF, and the SAF. But the war wouldn’t last this long without infrastructure and that infrastructure stretches across borders. It includes smuggling militias, rebel partners, and leaders like Touadéra, who make their money in the murk.

The Central African Republic is a cog in the system that keeps Sudan’s war running, not by leading the fight, but by making it possible. It helps move weapons, fighters, and money. It turns weak borders into open channels. As long as these quiet routes and silent partnerships stay intact, the war will keep grinding on, out of sight, but fully supplied.

But this isn’t just about Sudan’s conflict or story. It’s also CAR’s story. A country fractured by decades of foreign manipulation, conflict, no institutions, and predatory alliances. The RSF’s use of CAR is just one chapter in a longer story of how empire, capital, and opportunism have turned the country into a revolving door for extraction. By rebels, by mercenaries, by foreign states, and by its elites like Touadéra.

If the RSF’s corridor collapses, it won’t fix CAR. But it might mark the first rupture in a system that has kept the country trapped in endless cycles of conflict. Whether that rupture leads to a real shift depends on forces yet unseen: perhaps the government and its allies move to secure the borders and finally dismantle the fragmented rebel networks (though that seems unlikely, because peace isn’t profitable). Or perhaps, a new political force rises from within, one capable of uniting the country’s fractured groups and charting a future not defined by extraction or division. But that feels improbable. Because a unified, progressing CAR, a country cobbled together through colonial borders and never meant to function as a cohesive state, would challenge the very foundation of the global system that relies on African fragmentation.

Division, underdevelopment, and disorder aren’t accidental features of this system, they’re what hold it up. Culture, ethnicity, tribe, religion, and identity all matter and are beautiful things, but when they’re weaponized to justify violence, they become tools of the same machinery of control. If the Central African Republic were to break that pattern, if even one part of this system stopped working as intended, It could challenge the assumption that Africa must remain fragmented, extractable, and ruled from afar. If the continent drew the short stick, the Central African Republic got the splinter. But that’s precisely what makes it dangerous. If even a place like CAR refused to play its assigned role, it would reveal the truth: this system isn’t natural. It’s imposed. And it only survives because it’s obeyed.

Really informative and interesting article covering parts of Sudan and CAR that virtually get no attention by media. Well done

This is from Scroll XVI of my project The Hidden Clinic. I wrote it as a prayer—not a statement. Not for applause. Just rhythm for witness. https://thehiddenclinic.substack.com/p/to-the-ones-who-were-set-on-fire