the end of francophonie?

why north and west africa are turning to english... and away from france

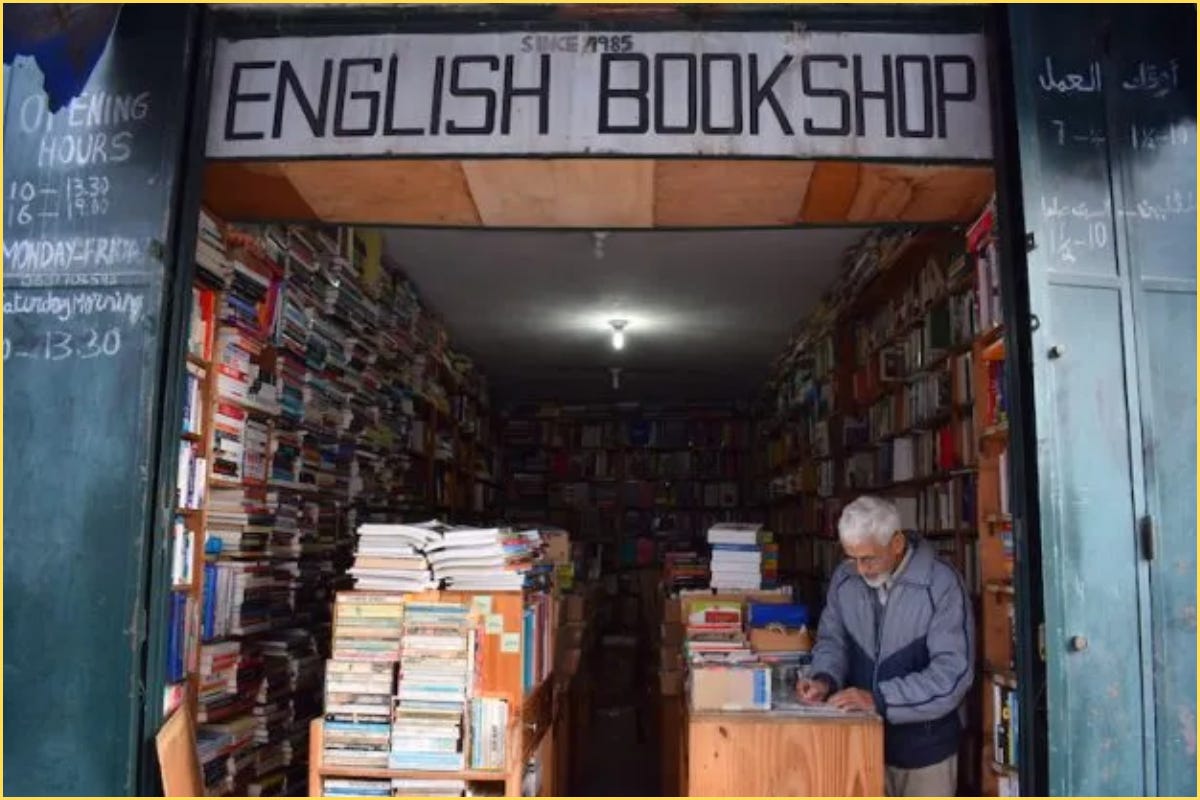

Essaouira, Morocco — In 2023, in a hostel over mint tea and cigarettes, a group of young men told me they refused to speak French. “It’s colonial,” one shrugged. “And useless.” They preferred English, the language of YouTube, job applications, and escape.

What seemed like youthful defiance is now national policy, not only in Morocco, but also across its eastern border. Earlier this month, Algeria announced that English will replace French as the language of instruction in science and medicine courses at its universities, starting in September 2025. It’s part of a broader shift: a linguistic reorientation away from its former colonizer.

Although officially framed as educational reform, the move is widely understood to be political. The announcement came just days before a spike in diplomatic tensions with France. That rupture began when France endorsed Morocco’s claims over Western Sahara in 2024, prompting Algeria to withdraw its ambassador. Then, just weeks after the language directive, French authorities arrested an Algerian consular employee in Paris, alleging involvement in the kidnapping of an anti-regime influencer. Algeria expelled 12 French diplomats; France responded in kind and recalled its ambassador. Now, Algeria is undertaking a deeper shift: dismantling one of France’s most persistent instruments of influence, the French language.

Algeria is not alone. Across West Africa and the Sahel, former French colonies are shedding France’s influence with unprecedented speed. Military juntas in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger have expelled French troops and withdrawn from the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie, accusing it of serving French geopolitical interests. In Senegal, long seen as a stable French ally, President Bassirou Diomaye Faye recently ordered the closure of a permanent French military base, citing national sovereignty. Chad, once a key French security partner, has ended its defense agreements with Paris. Côte d’Ivoire, while reaffirming its diplomatic ties with Paris, oversaw the withdrawal of French troops from their sole base in February 2025.

The rejection of French influence is increasingly visible, not only in military realignments, but in language, symbols, and public space. In parts of West Africa, signs bearing French names are being removed; French businesses have faced protests. President Emmanuel Macron has called French “the universal language of the African continent,” though he acknowledged in 2022 that “English is a new common language that people have accepted.”

Language, after all, shapes who gets educated, who controls the media, who gets hired, and who is heard. In much of Francophone Africa, French has come to symbolize not aspiration but exclusion: the language of bureaucracy, inequality, and a past many would rather leave behind.

English, by contrast, represents opportunity. It is the language of global business, science, digital platforms, and possibility. For many young North Africans, French feels increasingly obsolete: tied to colonial-era formalism and narrow cultural horizons. English opens doors, to international education, remote work, entrepreneurship, and global networks. Morocco, once a bastion of French linguistic dominance, has launched a sweeping national plan to phase English into all secondary schools by this year and to replace French in higher education by 2027. Even cabinet ministers have begun avoiding French in public appearances, favoring Arabic, English, or Spanish. It’s a striking shift, and a signal that across the Maghreb and the Sahel, the French language is not just fading. It is being deliberately set aside.

The irony is not lost on many. The British Empire colonized more territory than France ever did. But English, now the lingua franca of the internet, science, and international commerce, is increasingly seen as decoupled from its imperial origins.

For North African youth, English isn’t tied to empire. It’s a tool: a means to apply for scholarships abroad, land jobs with multinational firms, or build a digital presence that transcends borders. According to a 2021 survey by the British Council, 40 percent of Moroccan youth rank English as the most important language. Only 10 percent say the same about French.

That perceived neutrality gives English a kind of cultural flexibility French no longer enjoys. Where French is still associated with old hierarchies, English is seen as practical and empowering. Still, critics note that English’s global dominance comes with its own hierarchies, particularly in digital and academic spheres.

The transition won’t be easy. Algeria ranks near the bottom of global English proficiency indexes. Many professors lack the training to teach in English. Rural schools risk falling further behind. Experts say the shift will require years of investment, in teacher training, curriculum development, and access to English-language materials. Without that support, inequality could deepen even as French fades.

Still, the direction is set. And it’s generational.

This isn’t just about education policy. It’s a strategic shift, away from postcolonial dependency and toward a world where cultural capital comes from many centers, not just Paris.

Back in Essaouira, those young men weren’t making a cultural statement. They were being practical. French felt like a dead end. English felt like a way out.

sources/footnotes

The New Arab, Amid diplomatic rift with France, Algeria drops French and switches to English at universities, 2025.

Reuters, Algeria withdrew its ambassador after France backed Morocco’s Western Sahara autonomy plan, 2024

AP News, Algeria expels 12 French officials as diplomatic tensions reignite, 2025

RFI, Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso withdraw from French language body, 2025

VOA, Senegal to close foreign military bases, cuts ties to ex-colonial power France, 2024

AP News, Chad ends a defense cooperation agreement with France, its former colonial ruler, 2024

Assahifa, French language declining in North Africa, says Macron, 2022

British Council, Shift to English Report, 2021

Al Jazeera, From street names to textbooks, Senegal is rewriting French colonial memory, 2025

Anadolu Agency, France withdraws from its sole military base in Ivory Coast, 2025

Middle East Monitor, Morocco minister refuses to speak French during public event, 2023