the general who outgrew uganda

as south sudan descends into conflict, uganda's shadow grows longer, revealing the quiet ambitions of a regional strongman.

On May 3, airstrikes hit Old Fangak, a remote town in South Sudan’s Upper Nile state. The only hospital in the area, run by Médecins Sans Frontières, was destroyed, killing at least seven and wounding over twenty. The United Nations called it deliberate. The munitions were incendiary. There was no mistaking what this strike was meant to do.

Ugandan troops took part in the offensive. But their role wasn’t just tactical, it was political. They came not to stabilize, but to decide who would.

What’s unfolding in South Sudan isn’t a one-off. It’s the purest expression of a strategy President Yoweri Museveni has refined over decades: project force abroad to insulate power at home. Present Uganda as a regional problem-solver, while eroding democratic checks and tightening control over dissent. The contradiction isn’t new. What’s new is how blatant it has become.

the south sudan playbook

This is not the first time Uganda has intervened in South Sudan. In 2013, it deployed thousands of troops to prop up President Salva Kiir at the outbreak of civil war, helping repel rebel advances on Juba. That intervention marked a turning point in Uganda’s regional posture, revealing Museveni’s willingness to enforce political outcomes beyond his borders. All without multilateral cover or an international mandate. What’s happening now didn’t break precedent. It followed it, just more openly.

This time, Ugandan forces helped Kiir recapture towns from opposition loyal to Riek Machar. The same opposition Kiir arrested in March, in direct violation of the 2018 peace agreement. Uganda trained Kiir’s elite guards. It reportedly backed the promotion of Bol Mel, a powerful businessman, long-time presidential advisor, and Kiir’s alleged son-in-law, to vice president, sidelining Machar and consolidating power within the Dinka political elite.

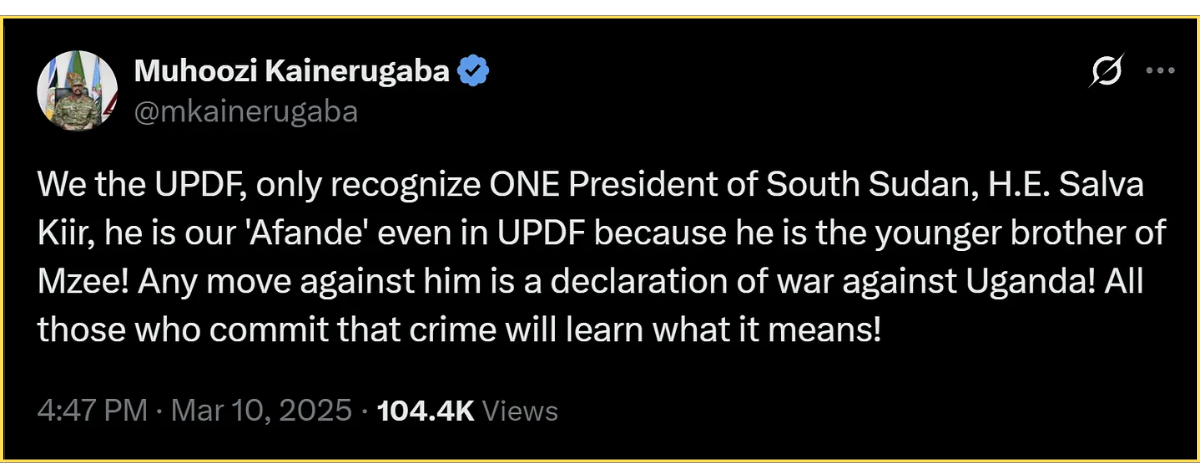

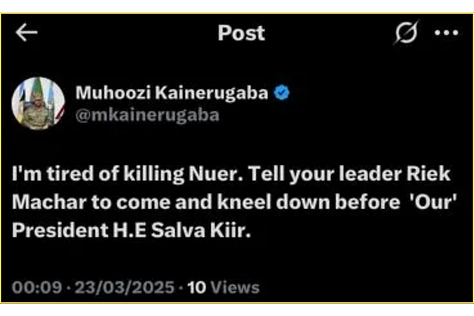

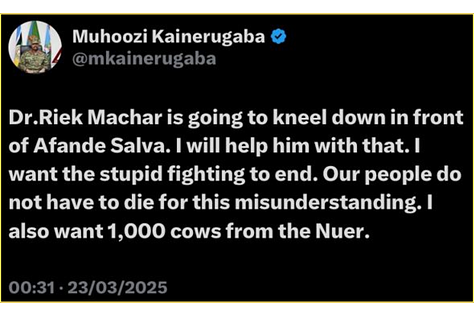

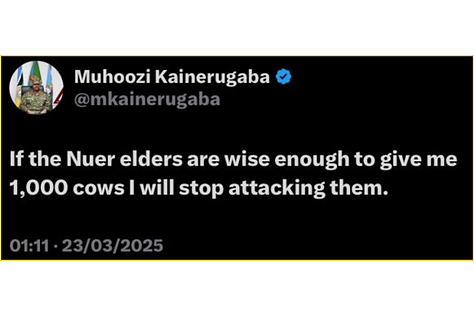

The message wasn’t subtle. Uganda’s military chief, Gen. Muhoozi Kainerugaba, publicly declared that Uganda recognizes only one legitimate authority in South Sudan: President Salva Kiir. Any opposition to him, he said, would be treated as a threat to Uganda’s interests.

This wasn’t diplomacy or peacekeeping. It was Uganda picking winners and making sure its interests won.

The stakes are both political and economic. South Sudan is Uganda’s largest export market. It’s also a strategic buffer: if South Sudan collapses, Uganda faces the blowback. More refugees, more militias, more instability crossing its borders. Backing Kiir helps Kampala contain that risk. Even if doing so makes the underlying conflict worse.

If journalism still matters to you. Consider subscribing. It keeps this work going, and it tells the algorithm that facts still have value.

the regional pattern

This is not new behavior. In Somalia, Uganda leads the African Union Transition Mission (ATMIS), maintaining a deployment of roughly 4,500 troops. The role brings both strategic prestige and steady international support. In recent years, Uganda has received over $21 million in U.S. military equipment, nearly $8.5 million in training aid, and additional infrastructure investment to support its peacekeeping operations.

The arrangement is straightforward: Uganda supplies troops. The West supplies funding.

But the costs are not theoretical. In May 2023, al-Shabaab militants overran a Ugandan base in Buulo Mareer, killing 54 soldiers, the deadliest single attack on Ugandan forces since their involvement began in 2007. President Museveni acknowledged the losses, blamed poor leadership, and promised consequences. Two officers were court-martialed. The mission continued.

There was no broader reckoning. No shift in doctrine. Uganda's presence remains, as does the logic behind it.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, Uganda’s presence is murkier and much longer-standing. Since the late 1990s, Ugandan troops have intervened repeatedly, often under the banner of counterinsurgency but with growing entanglements in resource exploitation. Officially, Uganda’s current operations target the ISIS-linked ADF militia. But a 2024 UN report accused Ugandan officers of backing the M23 rebels, including hosting meetings and supplying arms. Meanwhile, satellite imagery and trade data show a spike in Congolese gold smuggled through Uganda. The suspicion isn’t just corruption. It’s that Uganda’s military footprint in Congo has blurred into something closer to economic opportunism. Where conflict enables control, and deployments double as extraction strategies.

In each case (Congo, Somalia, South Sudan) the script repeats. A security crisis becomes a stage for intervention. Intervention becomes leverage. And leverage becomes insulation for a regime losing touch at home.

But South Sudan strips away even the pretense. There, Uganda isn’t operating under international mandates or multilateral cover. It is intervening unilaterally, propping up Salva Kiir, a president whose government has delayed elections, jailed critics, and presided over mass atrocities. His main rival, Riek Machar, is no democratic reformer either. His forces have their own record of abuses, including massacres and forced recruitment. But Uganda’s role isn’t about choosing the lesser evil. It’s about securing a regime that serves its interests. And in doing so, it is helping entrench one of the region’s most repressive governments.

the domestic cost

Museveni doesn’t rule by popularity. He rules by force. The National Unity Platform, led by opposition figure Bobi Wine, is targeted relentlessly. In 2025, ahead of planned protests, dozens of National Unity Platform supporters were abducted by security forces. Human Rights Watch has documented over 400 such cases in recent years. In one verified account, a man detained in a Kampala “safe house” in 2021 described being tortured with electric wires and held without charge for over a month, simply for attending opposition rallies.

That repression is sustained by corruption. Uganda ranks 140 out of 180 countries on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, below Nigeria and Pakistan. Military budgets balloon while public services wither. Contracts go to cronies. Oversight is cosmetic. The president’s official salary is modest (compared to other world leaders), about $183,000 annually, but his personal wealth remains opaque. No credible audits exist, but you have to remember that Museveni has been in power nearly four decades and oversees a patronage system where state resources routinely flow to loyalists. His brother-in-law and former foreign minister, Sam Kutesa, was named in a U.S. federal corruption case, where a Chinese energy executive was convicted of paying him a $500,000 bribe to secure business deals. Kutesa was never charged, but the payment, made to an account he controlled, was confirmed in court. The regime rewards loyalty and punishes inquiry. It doesn’t just govern through fear. It governs through extraction and through the careful concentration of favors.

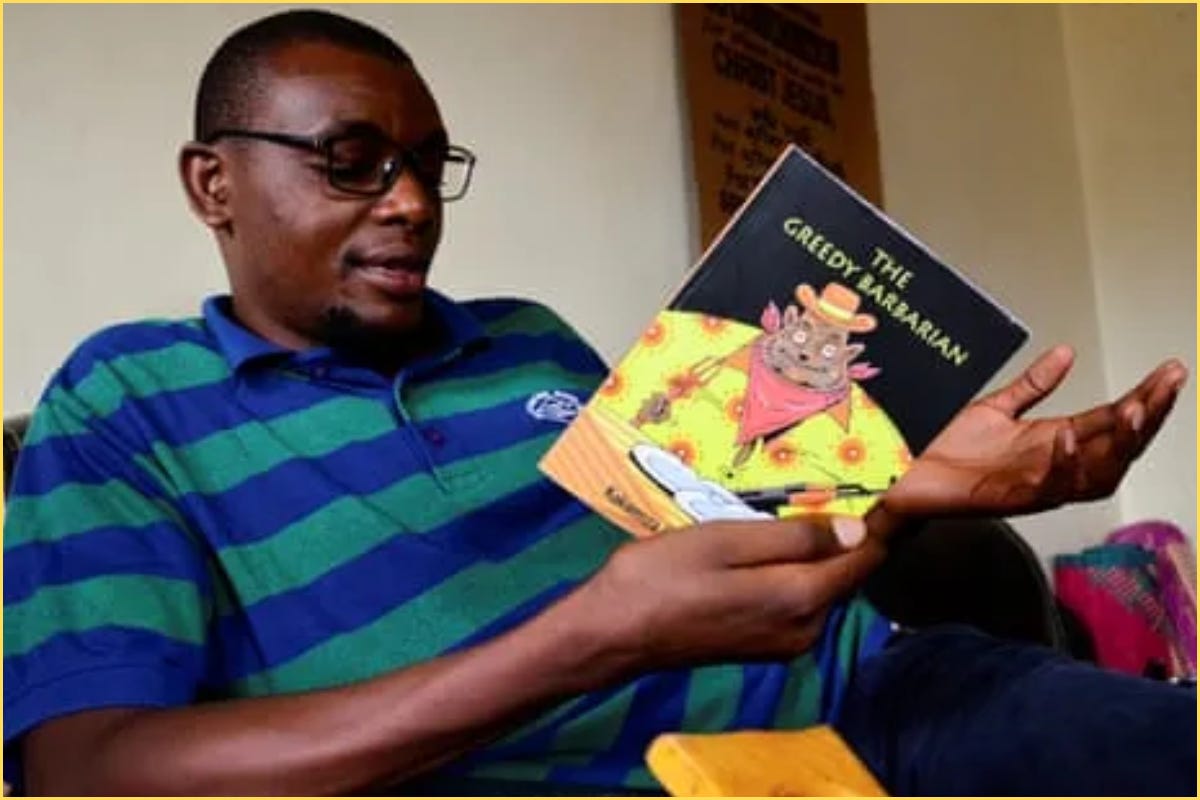

The system doesn’t just discourage scrutiny. It punishes it. Journalists who investigate Museveni’s government risk arrest or assault. In 2022, two were detained and beaten after publishing books critical of the regime. In 2021, novelist Kakwenza Rukirabashaija was abducted and tortured for mocking Museveni and his son on Twitter. Charges followed. So did exile. In Uganda, exposure is treated not as journalism, but as provocation.

In 2023, Museveni signed into law one of the harshest anti-LGBTQ statutes in the world. The move wasn’t ideological. It was theatrical. He cast the crackdown as a stand against Western cultural imperialism, invoking tradition, sovereignty, and morality. All while continuing to accept Western aid, security partnerships, and diplomatic cover. The law played well at home, especially in communities where the state has delivered more ideology than infrastructure. But it was scapegoating, staged as self-defense and most Western allies, while quick to condemn, were just as quick to move on, as Museveni remains useful.

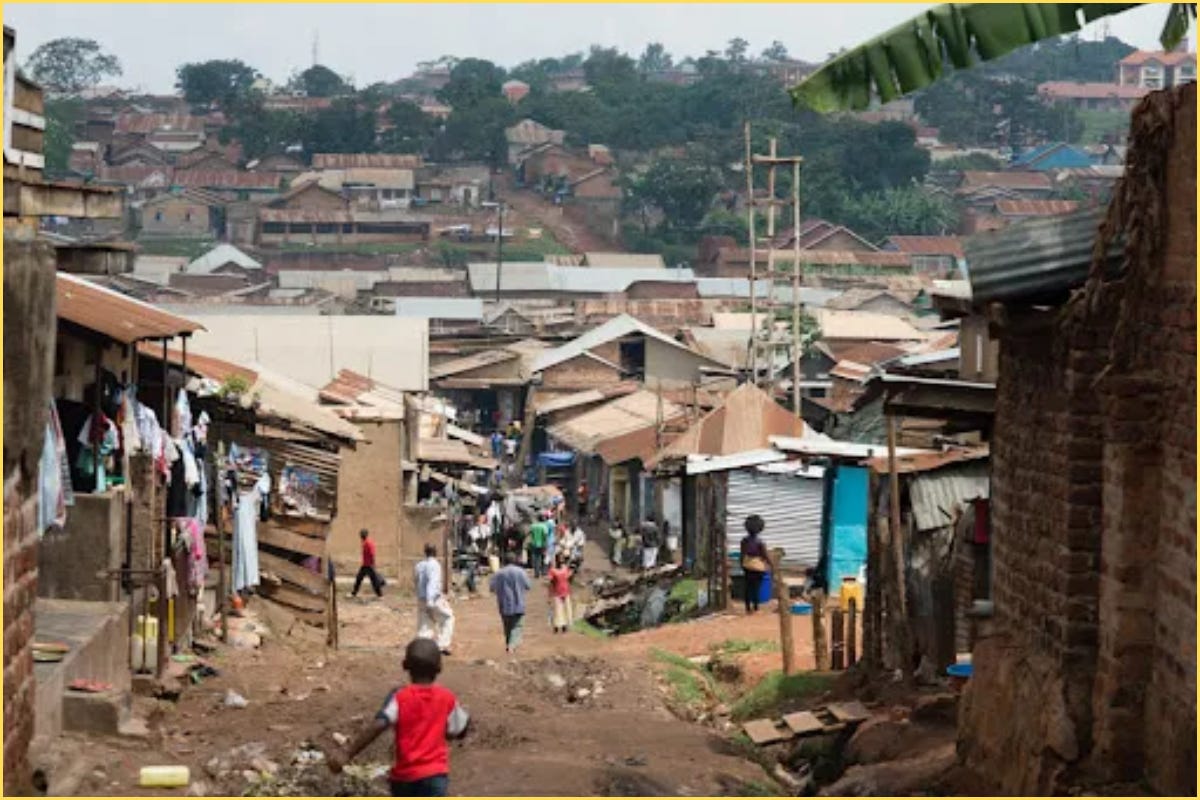

The model holds but only for those in power, and those convinced by its performance. Youth unemployment remains high, with more than a third of young Ugandans actively seeking work. Over 40 percent of the population lives on less than $2.15 a day. Inflation has slowed, but the effects are uneven: schools remain overcrowded, clinics underfunded, and infrastructure projects sporadic. For much of the population, especially the young, the promises of stability mean little without opportunity. What they get instead is rhetoric, repression, and a defense budget that keeps expanding, even as classrooms and clinics go neglected. The state isn’t failing to govern. It’s choosing to govern like this.

the heir and the gap

Uganda’s median age is under 17. Museveni is nearly 80. His heir apparent is his son, Gen. Muhoozi Kainerugaba. Who is the head of the military, the architect of Uganda’s foreign deployments, and a frequent provocateur on social media. (Muhoozi’s rise, and Uganda’s quiet drift toward dynastic rule, is something I’ve explored in more detail in another piece.)

how museveni turned uganda into a one-family state

After nearly four decades in power, President Yoweri Museveni has reshaped Uganda’s political system to entrench personal rule, undermining constitutional checks and positioning his son, Gen. Muhoozi…

This isn’t just about succession. It’s about a regime aging into irrelevance, led by a family that mistakes control for continuity. Uganda’s youth didn’t build this system. But they’re the ones expected to bear its costs. The repression, the poverty, and the institutional decay.

what future?

Uganda presents itself as a pillar of regional stability. In reality, it’s a strongman’s stage set. Built with foreign money, guarded by soldiers, and sustained through repression. Museveni doesn’t project power to distract from domestic weakness. He uses it to reinforce the system that keeps him in control. And his foreign partners have helped make that possible.

No airstrike in South Sudan, no peacekeeping mission in Somalia, no military push/gold corridor into eastern Congo will address the crisis inside Uganda. The contradiction isn’t subtle. And for Uganda’s youngest citizens, it’s not distant. It defines the world they’re coming of age in.

They understand the system. They know what it defends and what it discards.