the west’s favorite president in west africa

how alassane ouattara built a system the imf applauds, the west protects, and ivorians can’t vote out.

quick heads-up: I’ve been working on this one for a while, so a couple of the time references are from earlier drafts.

Fifteen years ago, the West threw its full moral weight behind Alassane Ouattara. They elevated him as the responsible adult in a country spiraling into chaos, the democrat who would restore institutions, the technocrat who would save Cote d’Ivoire from the strongman who refused to leave. They presented him as the antidote to Laurent Gbagbo’s stubbornness and as the embodiment of a new era of governance that’s transparent, open, fiscally sound, and integrated with the world. This was the man they told Ivorians, would rebuild a democracy shattered by two internal conflicts.

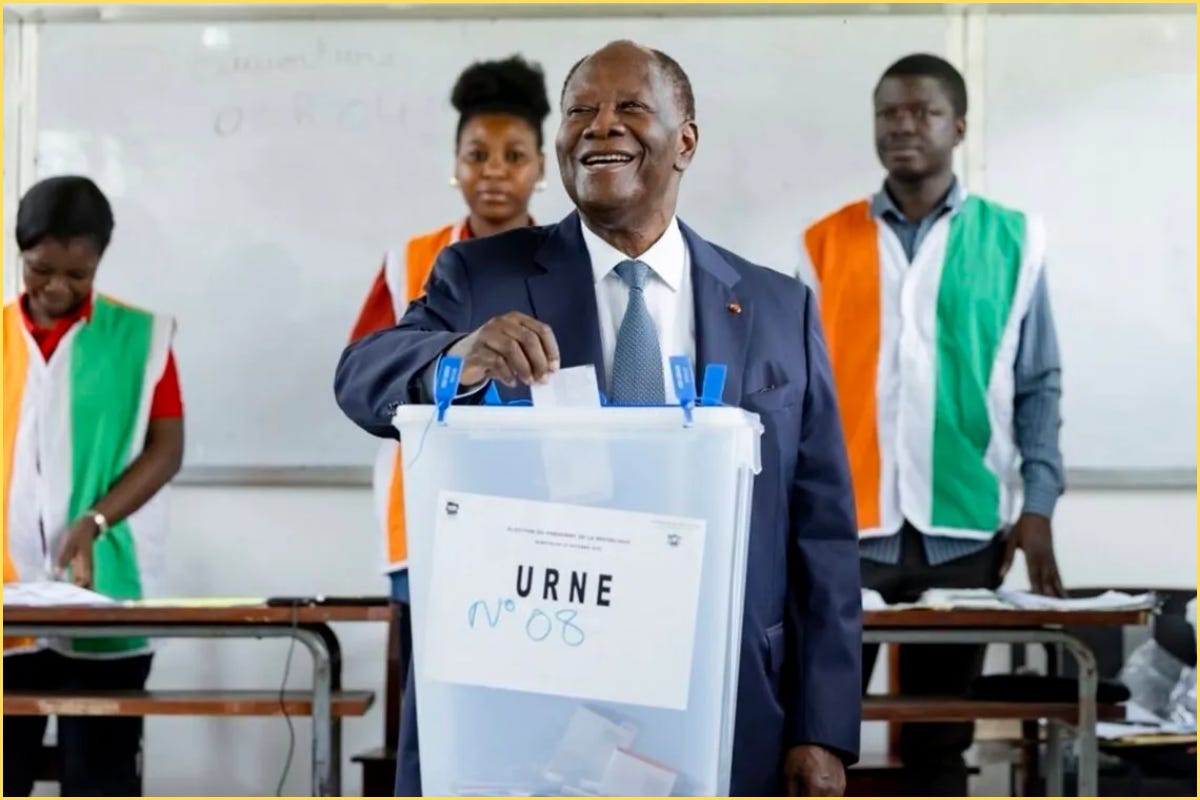

And now, the same man has secured a fourth term, after already pushing through an equally controversial third term by arguing that the 2016 constitution had “reset” his mandate. An interpretation widely condemned as unconstitutional. At 83 years old, he has tightened political space, disqualified opponents, controlled the electoral machinery, and choked dissent. All the while the very governments and institutions that once championed his democratic credentials remain silent. Not even uncomfortable. Just quiet. As if this was always the plan.

Because maybe it was.

a man designed in washington, polished in paris, installed in abidjan

To understand why nobody outside Cote d’Ivoire is protesting, why Washington doesn’t blink, why Paris doesn’t object, why the IMF keeps pumping money into the country, you have to understand the kind of figure Alassane Ouattara is. He is not just a former IMF official who happened to end up in politics. He is someone whose entire career was shaped inside the structures of global finance, someone the IMF trained, elevated, and treated as one of its own. For decades he absorbed its worldview, its priorities, and its institutional culture. By the time he emerged as a political actor, he embodied the IMF’s logic.

Alassane Ouattara’s employment biography on the IMF’s official website

But his rise didn’t depend on Washington alone. Long before the 2010 post‑election crisis (the violent standoff that left thousands dead after former President Gbagbo refused to step down), France had already positioned Ouattara as a trusted partner. This was part of a long French tradition of cultivating Western‑trained technocrats who could preserve the old economic order without appearing overtly colonial.

For decades, Paris relied on leaders who could do two things at once: speak the fluent, soothing language of Western financial institutions, and manage the delicate networks of political and business elites at home. Ouattara fit that script almost too perfectly. He studied abroad, built a career through the IMF, and internalized the economic doctrines France wanted its former colonies to follow. Doctrines that prioritized fiscal discipline, investment‑friendliness, and the stability of the CFA franc system that keeps West Africa tied to the French treasury.

In the 1980s and 1990s, when structural adjustment was the gospel of global finance, Alassane Ouattara was one of its senior priests. In 1990 he was appointed Prime Minister explicitly to implement Cote d’Ivoire’s structural adjustment program, a role that placed him at the center of the austerity doctrine reshaping the region. Structural adjustment was an ideological export and Ouattara became one of its most loyal evangelists. Privatize, liberalize, open up, cut subsidies, trust the market, discipline the budget, reassure investors. These were the pillars of an economic order that bound African economies to Western financial centers. France needed leaders who believed in them. Washington needed implementers. Ouattara was both.

By the time he stepped into Ivorian politics, he carried the entire playbook of Western economic policy in his bloodstream. He spoke the language Western lenders love. Stability, macroeconomic discipline, fiscal consolidation, risk mitigation, investor confidence. And when Paris looked at him, they saw continuity. They saw a future where Cote d’Ivoire remained anchored to the CFA franc, the French treasury, French corporations, French banks, and French strategic influence. To them, Ouattara was a modern Houphouët‑Boigny. Not the old power-broker of the cocoa barons, but the updated version shaped by global finance.

He also understood how to build what the IMF calls “credibility”, and “credibility” in the eyes of these institutions, rarely means democracy. It means predictability. It means comfort. It means knowing that when the phone rings in Abidjan, someone on the other end will speak the same language. Economically, politically, strategically speaking. Whether that language is English or French.

The West didn’t back Ouattara because he loved democracy. They supported him because he was theirs. He’s an IMF man. He’s a safe pair of hands in a region slipping into uncertainty. Democracy was the packaging. Economic alignment was the substance.

That is why today, as he bends the constitution even further to stay in power, they don’t oppose him. They don’t interfere. They don’t reprimand. They don’t even raise their voice.

It’s because he is their man.

the irony burns, but it is not an accident

When Laurent Gbagbo refused to step down after the internationally certified results of the 2010 election showed he had lost, major Western governments, including France, the United States, the EU, and the UN, quickly aligned behind Alassane Ouattara. They insisted that the electoral outcome had to be respected and that Gbagbo’s refusal threatened to push Cote d’Ivoire back into the instability of the 2000s. Western statements stressed the need to uphold institutions, protect the vote, and prevent another national crisis. The conflict was widely framed as a confrontation between an entrenched incumbent defying election results and a reform‑minded technocrat whom the international community recognized as the legitimate winner. In Western media and diplomatic language, Gbagbo became the autocrat clinging to power, and Ouattara the responsible statesman positioned to restore order and rebuild the country.

That was the narrative sold to Ivorians and to the world. When the situation escalated into violence, with at least 3,000 people killed between late 2010 and April 2011, the narrative hardened even further. France activated Opération Licorne, its long‑standing military mission in Cote d’Ivoire, to support UN forces already on the ground. The UN’s peacekeeping mission, UNOCI, moved to enforce the internationally recognized election results, backing Ouattara as the legitimate winner. Laurent Gbagbo was eventually arrested after a siege on his residence by pro‑Ouattara forces supported by French and UN troops. He was later transferred to the International Criminal Court in The Hague in November 2011. All of it was wrapped in the language of protecting democracy.

But the reality under the surface was more complicated. Western powers weren’t acting out of moral outrage or democratic principle, they were fighting for the continuity of a geo‑economic system. Cote d’Ivoire is the anchor of the Francophone West African economy, the largest market in the CFA zone, the engine that keeps the currency union credible. A prolonged crisis threatened not just political stability but a financial architecture Paris and Washington had no interest in losing. Protecting Ouattara was protecting that architecture.

And now, fifteen years later, the irony becomes impossible to ignore. Ouattara is not repeating Gbagbo’s playbook in identical form, but he is pursuing the same end result by staying in power beyond widely accepted constitutional limits. Gbagbo defied election results outright in 2010, triggering a deadly standoff; Ouattara has instead engineered the legal and institutional terrain so that he never faces a real contest. Different methods but with the same destination, a leader refusing to relinquish power and reshaping the system to make his continued rule possible. But this time the international outrage is gone. The press releases are gone. The moral arguments are gone. No one speaks of democracy. No one calls it a crisis. No one demands accountability.

The contradiction is the system revealing itself. Western governments never cared about Cote d’Ivoire’s democratic health. They only cared about its alignment. They only cared about a stable partner who wouldn’t challenge the fundamentals of the arrangement. Ouattara was the man who ensured that nothing foundational would ever be questioned. And now, when democracy becomes inconvenient to that vessel, the requirement is quietly discarded. The system simply updates itself. Stability over political openness, predictability over pluralism, continuity over constitutionalism.

Power protects its investments, not its principles.

the imf’s silence is their approval

People like to pretend the IMF is some neutral calculator, an institution above politics that is just crunching numbers and handing out advice. But that’s not how it works. The IMF is shaped by the countries that fund it and command its voting power. The United States can block anything it doesn’t like. Europe pushes its own priorities. And France, in francophone Africa, carries far more influence than people admit. In reality, nothing big moves through the IMF without Washington signing off first.

And yet, even as Cote d’Ivoire shuts down political space, the IMF continues approving large disbursements. In June, after reviewing Cote d’Ivoire’s economic programs, the IMF approved another round of support, releasing about US$758 million. Three months later, in September, IMF staff reached another agreement that cleared the way for an additional US$843.9 million pending Executive Board approval. Each review repeated the same polished language, “progress remains solid,” “reforms are on track,” “the authorities remain committed”, even as the country’s political environment narrowed. The Fund focuses on macroeconomic benchmarks, not democratic conditions, creating the sense that Cote d’Ivoire’s political reality exists in a different universe from the one the IMF chooses to evaluate.

The contrast with other countries only makes it clearer. When Egypt intensified its repression and filled its prisons, the IMF continued lending because Cairo remained central to regional security arrangements and economic stability in the Middle East. When Rwanda consolidated into a tightly controlled political system and also launched incursions into the neighboring country, DRC, its IMF programs continued smoothly because Paul Kagame delivered exactly the kind of fiscal discipline and macro‑stability the institution prioritizes. When Ethiopia fell into civil war, lending paused, but largely due to uncertainty and economic collapse, not because of human rights concerns. And when Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger broke with France and the West after their coups, their access to international financing shrank sharply. Not because their democracies had weakened, but because they had stepped outside the political and economic architecture that underpins IMF engagement.

Cote d’Ivoire hasn’t stepped outside that architecture. It hasn’t challenged the system or disrupted the economic order the IMF and its shareholders depend on. And because it stays inside the framework, the framework continues to reward it.

It still serves the system. So the system still serves it.

france’s last stronghold cannot be allowed to fall

If you want to understand why Paris has not muttered a word about Ouattara’s fourth run, look north. France has been chased out of Mali, humiliated in Burkina Faso, expelled from Niger, put simply, the whole Sahel region that France once relied on as the center of its influence has now turned sharply against it. Its influence has evaporated in a matter of years.

Cote d’Ivoire is one of the last major francophone economies where Paris still holds deep economic influence, even as its soldiers leave the region. French firms are structurally embedded in key sectors. Eranove, through its subsidiary CIPREL, runs one of the country’s main independent power producers and the largest thermal plant on the grid. TotalEnergies is the leading fuel distributor and a major player in offshore oil and gas. Orange Cote d’Ivoire dominates the telecom market. Société Générale’s Ivorian arm remains one of the largest banks in West Africa. A French consortium of Bouygues, Alstom, Colas Rail and Keolis is building Abidjan’s metro system. And the Agence Française de Développement finances markets, urban upgrading schemes, and transport corridors across the country.

These are not isolated deals, they form an ecosystem and layered over all of it is the CFA franc. It is not the only place where France maintains interests, but it is by far one of the most strategically important ones left. The day Cote d’Ivoire chooses another direction is the day France becomes a spectator, not a player, in African affairs.

Macron knows this. The entire French foreign policy establishment knows this.

Which is why Paris will accept virtually anything Ouattara does, as long as he keeps the system stable and the country aligned.

If the choice is between democracy and a loyal partner, France will choose the partner every time.

the u.s. isn’t acting out of principle, it’s acting out of strategic self-interest

Meanwhile, Washington sees Cote d’Ivoire as one of the last reliable islands in a turbulent region. The Sahel has been swallowed by coups. Guinea is unpredictable. Chad is fragile. Nigeria is overwhelmed. Senegal is redefining itself. Liberia remains volatile. Sierra Leone is wobbling between stability and crisis. Ghana is stable but smaller.

Under the Global Fragility Act, Cote d’Ivoire is included among the five coastal West African countries placed into a ten‑year U.S. stabilization strategy. Benin, Ghana, Guinea, Togo, and Cote d’Ivoire. The State Department reports that the United States has committed nearly US$300 million in stability and security assistance to this corridor since 2022, consistently presenting Cote d’Ivoire as the anchor of that regional effort.

Stability, not democratic standards, drives U.S. engagement.

In this context, an IMF‑aligned technocrat running the region’s most important economy is not just acceptable to Washington, it is ideal. He aligns with U.S. security priorities, poses no threat to American influence, and keeps the coastal corridor predictable. And so the U.S. stays quiet, signs off on IMF lending rounds, frames the partnership in the language of “resilience” and “counter‑extremism,” and lets the financial institutions deliver the real message that Cote d’Ivoire is too important to lose, and too strategically positioned to antagonize over constitutional decay.

inside cote d’ivoire, the opposition is learning this the hard way

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to pieces & periods to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.