türkiye's expanding footprint in somalia: strategic partner or neo-colonial power?

a landmark oil deal deepens a decade-old alliance, but raises urgent questions about sovereignty, environmental risks, and the true cost of foreign investment.

When Somalia signed a sweeping oil and gas exploration deal with Turkey in March 2024, granting Turkish entities rights to up to 90% of production revenues, it marked a dramatic expansion of their decade-long partnership. But across the Horn of Africa, the agreement revived old fears: that promises of development may once again mask a deeper pattern of foreign exploitation.

The newly disclosed text of the agreement reveals just how expansive Turkey’s rights are. Turkish entities, primarily the state-owned Turkish Petroleum Corporation (TPAO), are entitled to recover up to 90% of annual oil and gas production as cost recovery. Somalia, meanwhile, would collect a royalty capped at 5% until Turkey recoups its expenses, a process that could stretch for years, depending on market prices and production rates.

In return, Turkey assumes the financial burden of exploration without paying standard industry fees such as signature bonuses, development bonuses, or administrative costs. It can export its share of hydrocarbons freely at international market rates, and settle any disputes under Turkish-controlled arbitration courts.

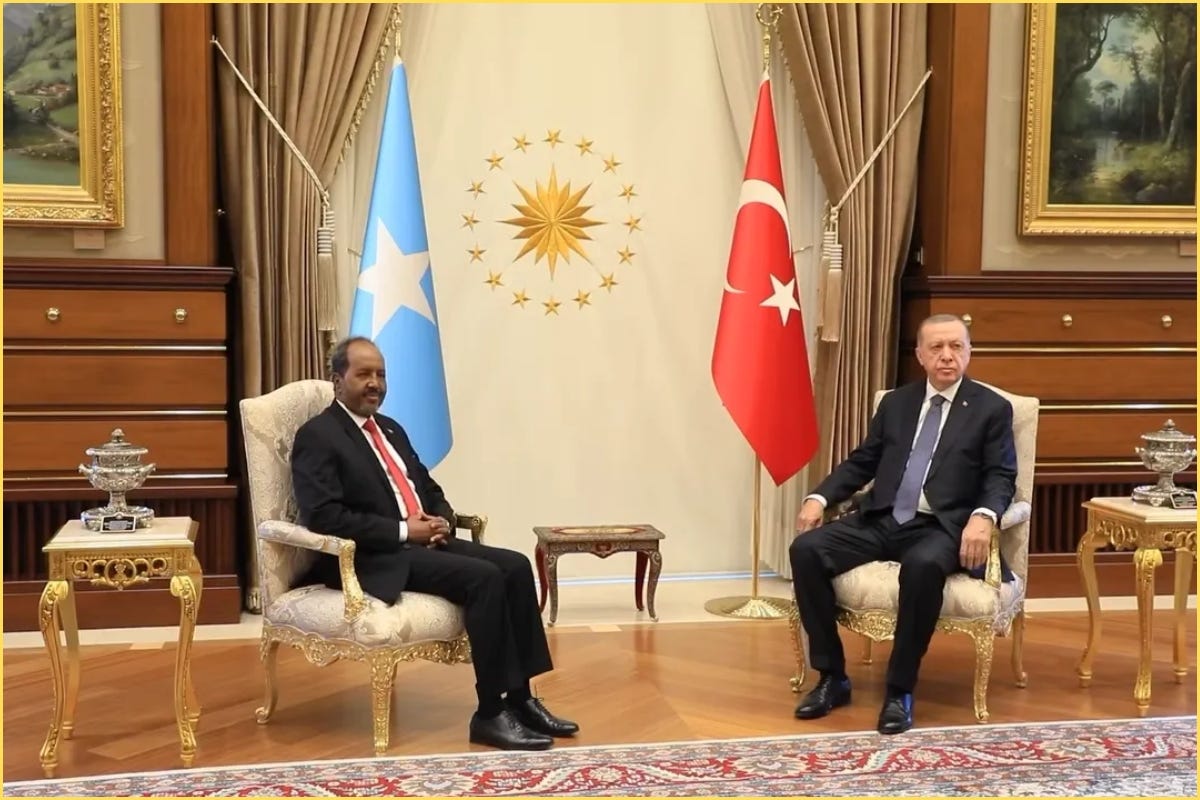

Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud has defended the deal, calling it a “mutually beneficial agreement” and emphasizing that Somalia is, for the first time in its history, beginning to explore its own oil potential. He argues that Turkey was the first and only country willing to invest when others stayed away and remains one of Somalia’s strongest international partners.

Yet critics, from Somali parliamentarians to legal analysts and civil society groups, warn that the structure of the deal heavily favors Turkish interests. For a country still struggling to rebuild after decades of war, famine, and weak governance, ceding such expansive rights to a foreign power has revived painful memories of colonial-style resource extraction.

a deeper entanglement

Turkey’s involvement in Somalia is not new, but it has accelerated sharply over the past year.

Following recent gains by Al-Shabaab insurgents near Mogadishu, Turkey nearly doubled its military personnel at Camp Turksom, its largest overseas military base. Ankara also deployed armed drones and pledged expanded counterterrorism support, although it has stopped short of direct engagement against Al-Shabaab.

At the same time, Turkish companies operate Mogadishu’s airport and seaport. Turkish NGOs lead major humanitarian efforts, while Ankara has pledged to help develop Somalia’s navy and secure its territorial waters.

This strategic relationship, however, did not begin with oil or military ambitions. It traces back to 2011, when Turkey was among the few non-African nations to step in during Somalia’s devastating famine. Then Prime Minister Erdoğan became the first non-African leader to visit Mogadishu in decades, bringing significant humanitarian aid when most of the international community stayed away. That early engagement forged a deep reservoir of trust and goodwill, which Turkey has steadily expanded into infrastructure projects, diplomatic initiatives, and security cooperation.

Today, Turkey’s presence in Somalia spans the military, economic, political, and humanitarian sectors, a comprehensive strategic footprint built over more than a decade.

For Turkey, Somalia offers:

A gateway to the Red Sea and Indian Ocean trade routes

Access to untapped oil and gas reserves

A platform to expand influence across East Africa

An opportunity to project itself as a culturally aligned Muslim partner, distinct from Western and Chinese powers

Turkey’s broader Africa strategy focuses on cultivating deep, targeted relationships where larger powers, like the U.S., China, Russia, have either neglected, exploited, or operated at arm’s length. Unlike China’s debt-heavy infrastructure model or Russia’s reliance on mercenaries, Turkey blends humanitarian aid, defense agreements, economic investments, and soft-power diplomacy. This allows Ankara to present itself as a less-threatening partner, particularly in Muslim-majority countries like Somalia.

strategic partnership or unequal deal?

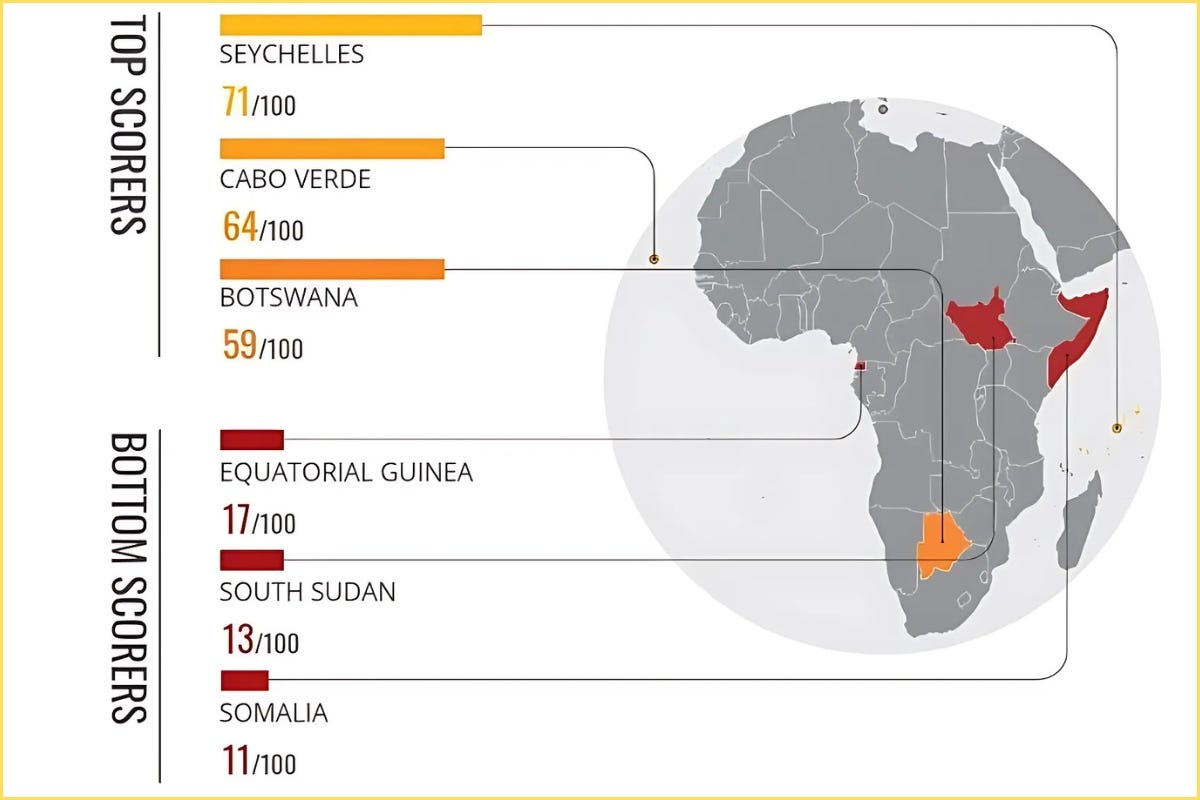

The tension in Somalia reflects a broader question facing many African states: how do you balance the desperate need for investment against the risk of losing control over national resources?

There is no doubt Somalia benefits from Turkish engagement. Without Turkey, critical infrastructure such as airports, hospitals, and military training programs might not exist in Mogadishu today. Turkey was the first non-African country to meaningfully invest after Somalia’s collapse in the 1990s, and for many Somalis, that early support remains deeply appreciated.

But the terms of the new oil agreement, 90% cost recovery, minimal 5% royalties, and Turkish legal jurisdiction over disputes, raise serious concerns. Members of Somalia’s Parliamentary Natural Resources Committee have publicly criticized the deal for being signed without consultation or parliamentary approval. Legal experts have warned that the agreement may violate Somalia’s 2020 Petroleum Law and the 2012 Provisional Constitution.

Turkey, having cultivated strong public goodwill over the past decade, had an opportunity to reinforce that trust through a more balanced deal. A revenue-sharing structure that allowed Somalia a larger initial stake, could have honored the partnership without compromising Turkey’s ability to recover its costs. Instead, the sweeping financial and legal privileges secured by Ankara risk portraying it less as a partner and more as a dominant actor with outsized leverage.

The decision to handle legal disputes exclusively in Turkish courts in Istanbul further compounds the imbalance. A joint Somali-Turkish arbitration panel. or at minimum an internationally neutral forum, would have better preserved Somalia’s sovereignty.

Still, realities on the ground complicate the story. Somalia’s government remains plagued by corruption and institutional weakness. In that context, Turkish officials may have sought strong legal protections not purely out of self-interest, but to safeguard their investments against instability, mismanagement, or sabotage.

Then there is the climate dimension. As the world races toward a post-fossil fuel future, Somalia’s heavy bet on hydrocarbons is fraught with risk. Already on the frontlines of climate change, with rising temperatures, droughts, and extreme weather displacing millions, Somalia’s fragile ecosystems could suffer further under poorly managed oil extraction.

Somalia faces a stark dilemma: oil could bring short-term revenue to rebuild the state or it could deepen environmental degradation, corruption, and foreign dependence.

Somalia’s oil deal with Turkey stands as both an opportunity and a warning. It could seed the foundations of economic recovery, or entrench cycles of environmental destruction and external control. In the end, how this partnership unfolds will depend less on Ankara’s ambitions and more on whether Somali leaders can defend their country's long-term sovereignty. For Somalia, and for Africa at large, the question remains: is this a new beginning or a familiar story retold?

sources/footnotes

Middle East Eye, Turkey doubles troops in Somalia amid Al-Shabab offensive, April 2025.

Nordic Monitor, Turkey secures rights to 90% of oil and gas output in Somalia deal, April 2025.

Middle East Eye, Somali president defends Turkey oil deal amid backlash, April 2025.

Government of Türkiye and Government of Somalia, Agreement in the Field of Hydrocarbons, signed March 7, 2024.

Reuters, Turkey signs energy cooperation deal with Somalia, March 2024.

Wardheer News, Legal, Policy, and Constitutional Analysis of the Türkiye–Somalia Hydrocarbon Agreement, 2025.

Who Owns Africa, Somalia’s oil deal with Turkey sparks environmental controversy, 2025.