uganda's president won the country in a war and he’s still using it to stay in power

how museveni’s past still shapes uganda’s politics, youth, and control

On November 30, Uganda’s president, Yoweri Museveni, sat down with a group of young people on a youth-focused podcast and reached for a comparison he has relied on for decades. When he was 26, he said, he went to the bush and took up arms. Today’s youth, by contrast, seemed to him unserious, too focused on culture, trends, and online life rather than sacrifice.

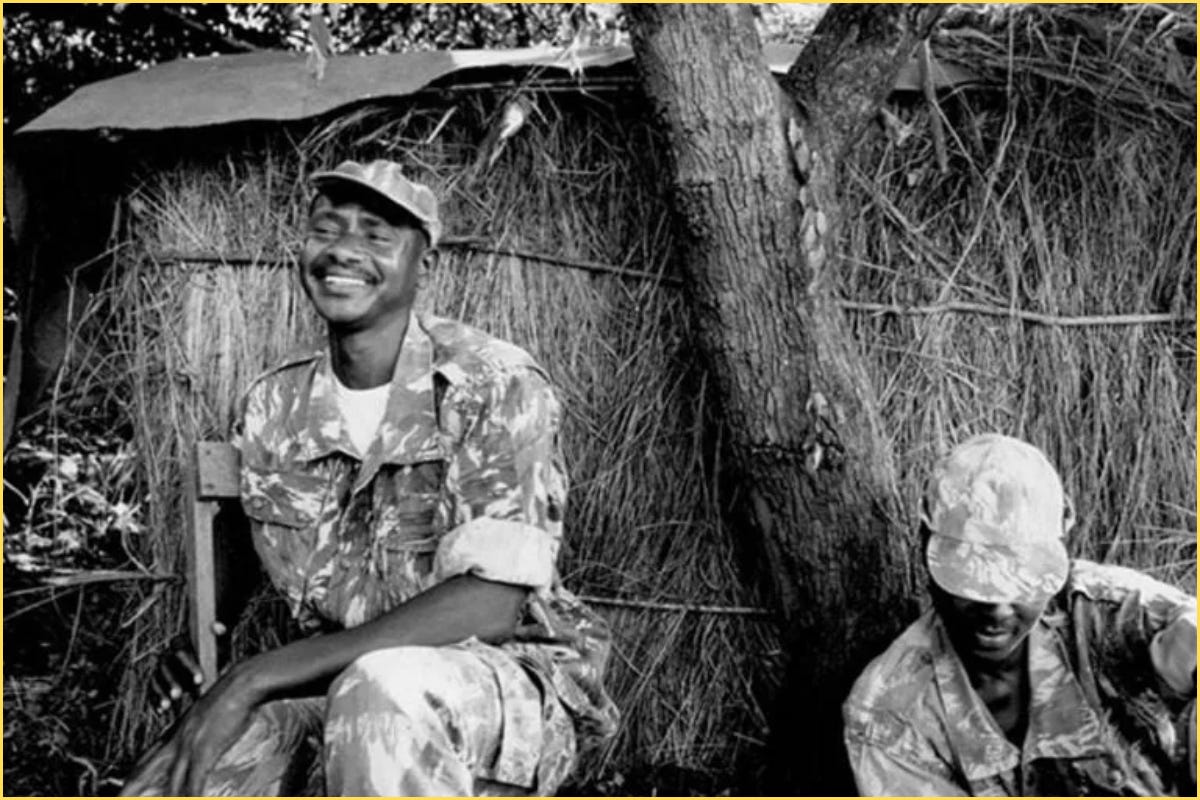

To understand why this comment matters, a bit of context is necessary. Museveni did not come to power through elections. He came to power through a five-year guerrilla war that ended in 1986. That victory became the founding story of modern Uganda. Forty years later, Museveni, 81 years old, is still president. Making him one of the longest-serving leaders in the world.

The comment was not a call for young people to take up arms. If anyone tried to act on it literally, the state would crush them because armed rebellion is now treated as terrorism. But the comparison still matters, because it exposes a basic contradiction in Uganda’s political system: power was won through rebellion, yet any serious challenge to power today is treated as illegitimate.

The bush war is not just history in Uganda. It is the moral backbone of the state. It is used to justify long rule, discipline dissent, and frame opponents as reckless or ungrateful. At the same time, the lesson of that history, that power can be challenged, is locked away. Violence was justified then. It is forbidden now. The past is honored, but its logic is off-limits.

This contradiction shapes everyday politics. Uganda holds elections, but they are widely seen as constrained. Opposition figures are monitored, harassed, and detained. Protests require police permission under public order laws that courts have partly struck down, only for enforcement to continue under new names. Online space follows the same pattern. In 2018, the government introduced a daily tax on social media use. During the January 2021 elections, the internet was shut down nationwide. More recently, bloggers and TikTok users have been arrested under computer misuse laws for criticizing the president. In some cases receiving prison sentences simply for posting videos that mocked or criticized Museveni or his family.

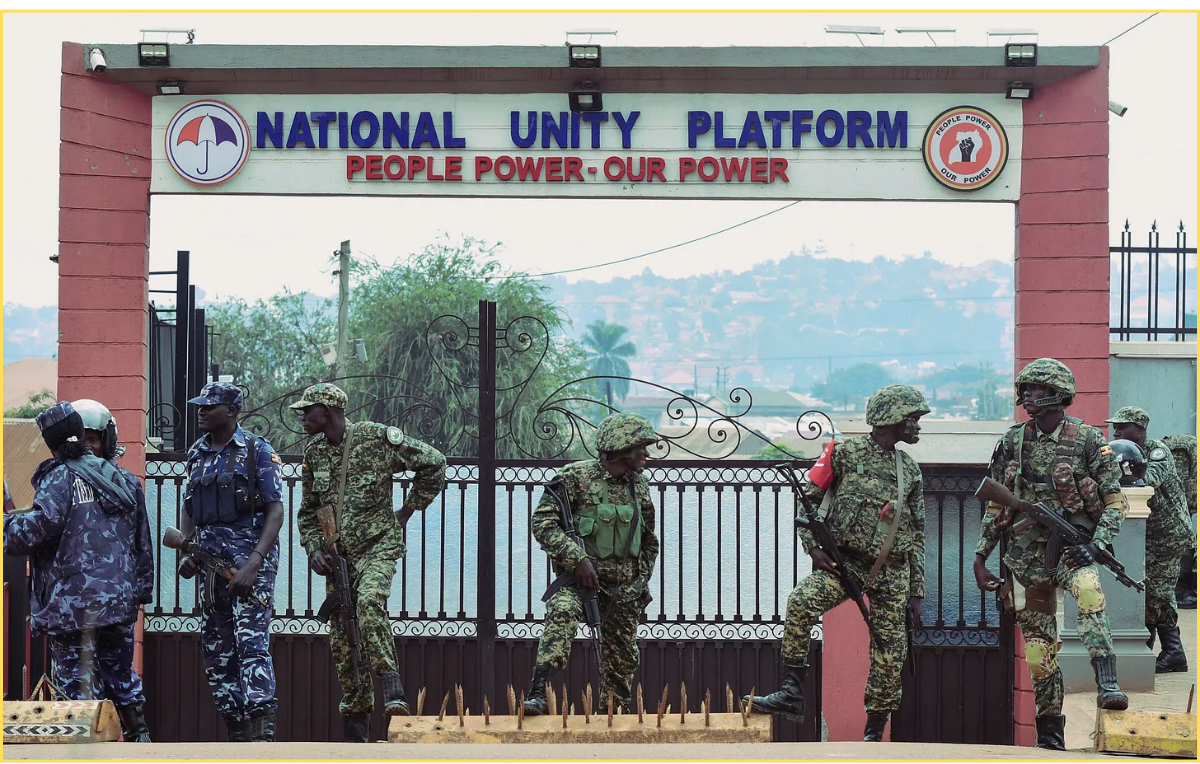

These are not isolated incidents. This year, as Uganda moves towards another election cycle (elections will be held next month, January 2026), security forces detained hundreds of opposition supporters linked to the National Unity Platform (NUP), the country’s main opposition party. The United Nations warned of growing arbitrary arrests, the suppression of rallies, and intimidation of journalists. Politics still exists in Uganda, but only within tightly controlled limits.

The generational clash is not abstract. The opposition itself is led and powered by younger Ugandans. Bobi Wine, the leader of the National Unity Platform, is 43, a generation removed from Museveni’s 1980s liberation story (Museveni was 41 when he took power in 1986). His movement draws heavily on young people in a country where roughly three-quarters of the population is under 30. When Museveni dismisses “the youth,” he is talking about the country’s largest political constituency.

Uganda is heading into a national election, with Museveni seeking another term and Bobi Wine once again challenging him. As the campaign has intensified, so has the rhetoric. Wine has openly described the opposition’s campaign trail as resembling a battleground, accusing security forces of targeting his supporters and disrupting rallies. He has also framed the election as a referendum on decades of unfulfilled promises to farmers, workers, and young people locked out of economic opportunity. Museveni, by contrast, has emphasized stability, experience, and continuity. These are things that rely heavily on his liberation-era credentials.

This is why Museveni’s comparison unsettles rather than inspires. When he asks what young people have “done,” he is speaking to a generation that has grown up with few real ways to influence power. Armed struggle is (ofcourse) illegal. Peaceful protest is restricted. Elections offer limited change. Courts are widely seen as aligned with the executive. The state asks for patience but offers no clear path to transition and it increasingly looks like the ruling system is quietly positioning Museveni’s son, Muhoozi Kainerugaba, as the eventual successor.

If you want the deeper backstory on the succession question, here is an article I wrote back in May on how Muhoozi is being positioned:

how museveni turned uganda into a one-family state

After nearly four decades in power, President Yoweri Museveni has reshaped Uganda’s political system to entrench personal rule, undermining constitutional checks and positioning his son, Gen. Muhoozi…

starlink and the politics of selective connectivity

Museveni’s moves becomes clearer when placed next to his recent enthusiasm for technology. In April, he welcomed talks with representatives of Elon Musk’s Starlink, calling discussions about expanding satellite internet access “productive.” He framed the talks as part of an effort to expand internet access, including in hard-to-reach areas where traditional networks are limited.

At first glance, this seems to clash with the government’s record of trying to control online speech. But it actually makes sense. Starlink is a tool for getting internet access, not a tool for protecting free speech. And because it comes from satellites, it can reduce how much the government has to rely on local companies, fiber cables, and other domestic networks. This means fewer local players can resist or complicate what the state wants.

Access can still be controlled. Terminals must be licensed and imported. Prices can limit who uses the service. Rollouts can favor businesses, government institutions and connected people over political organizers.

The government does not oppose the internet itself. It opposes organization. Online business, digital payments, remote work, and education are encouraged. Political mobilization that threatens power is not. Growth is welcome. Collective pressure is not.

After shutting down the internet nationwide during the January 2021 election, the state has already shown it is willing to cut off the public entirely during moments of political risk. And there are signs that this logic could be tested again in the January 2026 vote. Government figures have publicly floated the idea that internet access could be interrupted if authorities claim it is being used to “incite violence”, while the opposition has warned supporters to prepare for disruptions.

Satellite internet adds a new option to that toolbox. It introduces the possibility of cutting mass access while keeping the system online for the state. Maintaining connectivity for trusted institutions, security agencies, and key economic actors even as ordinary people are pushed into the dark.

Put simply, Museveni is trying to have it both ways. He celebrates the story of “we fought for this country,” but treats any serious challenge to his power as illegitimate. He promotes a modern, tech-driven future where young people are encouraged to build businesses and chase personal success, but not to organize politically in ways that could change who governs or allow them to shape the political and economic decisions that affect their lives, even though they make up the country’s largest constituency.

That is why he keeps returning to the bush war. It is still his strongest answer to the one question the system struggles to explain, why power has never changed hands. And it can land like a provocation, a way of daring younger Ugandans to match the sacrifice of the past, while assuming the state can crush any movement before it becomes a real threat. As the war fades from living memory and elections feel less credible, the old story has to be repeated louder and more often to justify permanence.

Its pretty ironic that by reminding people how power was actually won, the regime weakens the legitimacy of the order it defends. Over time, revolutionary history can either be translated into stable governing institutions or be endlessly recycled as proof of entitlement to rule. Stable systems do not need to keep pointing back to old wars to justify who is in charge. They rely on clear rules and institutions that explain how power works, how leaders change, and where authority comes from. And if leaders can’t point to rules, many try another route, ruling effectively, meaning actually improving people’s lives and giving them a real stake in the country’s economic future or at least creating the convincing illusion of effective rule, so people stay quiet. If you do neither, you end up with no real legitimacy, only force.

Uganda is still ruled using the language of liberation, but the state is clearly uncomfortable with what that language really means. As the generation that remembers the fighting disappears, the question Museveni asks young people, what have you done?, may slowly turn back on the system he created, what has it actually done for the people since the bush war?