why ethiopia and eritrea are sliding back toward war

six years after a nobel prize handshake, the two countries are once again in confrontation. this time with more players, more stakes, and fewer illusions.

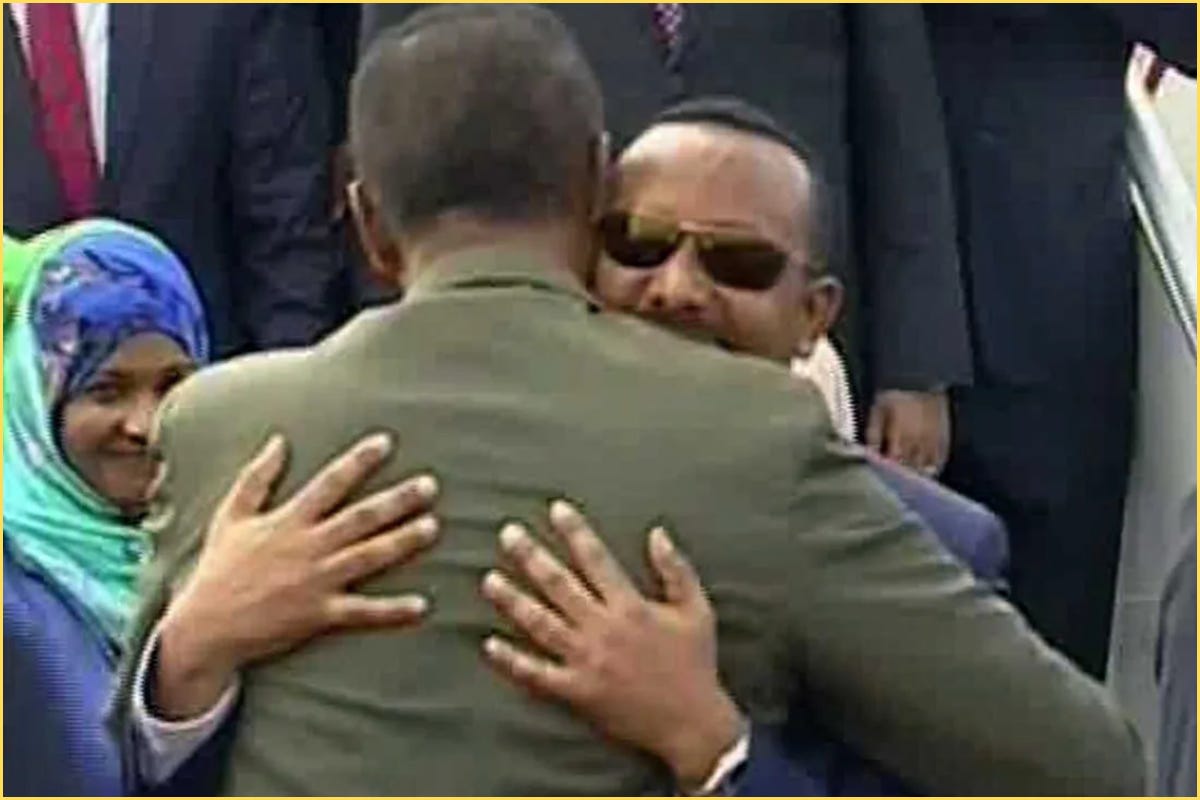

In 2019, Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed received the Nobel Peace Prize for ending a 20-year military standoff with Eritrea. The handshake with President Isaias Afwerki marked a rare moment of reconciliation in a region defined by division. Six years later, that hope has collapsed.

Ethiopia and Eritrea are again edging toward conflict. Military buildups along their shared border, accusations of proxy warfare, and claims to Red Sea access suggest a dangerous regression. What was once hailed as a model for post-conflict diplomacy now stands as a cautionary tale of unresolved grievances and geopolitical miscalculation.

tigray, the war that undermined the peace

The undoing began not with border disputes, but with civil war. In November 2020, Abiy launched a military campaign against the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), a once-dominant force in Ethiopian politics. Eritrea joined the offensive, not as an ally of Abiy, but as an enemy of the TPLF, whose leaders it had long despised.

The war was devastating. Independent estimates place the death toll at over 600,000. Yet when peace talks concluded in 2022 with the Pretoria Agreement, which was negotiated without Eritrea's participation, Asmara found itself excluded from a process that defined the region’s future. The deal required the withdrawal of foreign forces from Tigray. Eritrea, despite being a key belligerent, did not.

In the years since, Eritrean forces have maintained a presence in northern Ethiopia, notably occupying parts of the Irob district in Tigray despite the Pretoria Agreement's call for withdrawal. The Eritrean military has been implicated in abuses, including looting, forced disappearances, and harassment of civilians. Eritrean troops have also reportedly conducted operations beyond the border zone, supported dissident Tigrayan factions, and remained embedded in areas where accountability and humanitarian access remain limited. These activities, far from winding down after the ceasefire, have cemented Asmara’s presence and influence inside Ethiopia.

the red sea standoff

Geography plays a central role in the rising tension. Ethiopia, the world’s most populous landlocked nation, once controlled direct access to the Red Sea through the port of Assab until Eritrea gained independence in 1993. Ethiopia continued using Assab until the 1998–2000 border war severed ties. Since then, Ethiopia has relied almost exclusively on Djibouti’s ports, paying over $1.6 billion annually in fees. For Abiy, this is not just an economic burden, it’s a strategic liability that constrains the country’s autonomy and regional leverage.

In 2023, Abiy called sea access an “existential issue” for Ethiopia and described the loss of Eritrea’s coastline as a “historical mistake”. Last year, his government signed a memorandum of understanding with the self-declared republic of Somaliland to access the port of Berbera. The deal offered Ethiopia a 50-year lease in exchange for potential diplomatic recognition. But it quickly ignited a firestorm: Somalia’s federal government denounced it as a breach of sovereignty, recalled its ambassador, and annulled the agreement through emergency legislation. Under pressure from regional actors and mediation led by Türkiye, Addis Ababa appeared to de-escalate.

With the Somaliland corridor now politically radioactive and operationally uncertain, Abiy has turned back to Eritrea’s Assab. Although the administration insists it seeks resolution through dialogue, recent Ethiopian troop deployments near the Eritrean frontier and belligerent state media rhetoric have alarmed Asmara. Eritrea responded with nationwide mobilization, reinforcing its military presence along the border.

Ethiopia and Eritrea are edging toward war, not through a clear decision, but through choices that increasingly resemble one. In the Horn of Africa, conflict doesn’t arrive by announcement. It accumulates, act by act, until denial no longer holds.

the fracture within tigray

Tigray remains a flashpoint. While the Pretoria Agreement paused direct hostilities between the federal government and the TPLF, it also laid bare internal fractures. The once-unified leadership of the TPLF has splintered: one faction, headed by Getachew Reda, leads the region’s interim administration; the other, loyal to former chairman Debretsion Gebremichael, has challenged that authority on political and military fronts.

Though allies during the war, the post-conflict transition fractured the relationship between the two. Getachew, viewed by some as a pragmatist, by others as a tactician exploiting the moment to sideline his former comrade, emerged as the federal government’s preferred partner and chief face of the Pretoria deal. Debretsion, despite commanding grassroots loyalty and having led Tigray through war, was cut out of the postwar architecture. To him and his supporters, the deal wasn’t peace, It was capitulation. The fallout was swift. Loyalties fractured, and the question of representation and of who governs Tigray became not just political, but existential.

Eritrea’s position has remained uncompromising. Its intervention on the ground in the Tigray war marked a decisive turn in favor of the federal government, helping to roll back TPLF advances at a critical moment. For Eritrea’s leadership, the TPLF has never been just a political opponent, it has been a persistent and existential threat dating back to the split between the two movements in the 1990s, following their joint struggle against the Derg (the Marxist-Leninist military junta, led by Mengistu Haile Mariam, that ruled Ethiopia from 1974 to 1991). While they once fought side by side, they diverged sharply over ideology, power, and leadership in the post-Mengistu era. That hostility shaped Eritrea’s military decisions and continues to shape its posture in the region. To President Isaias Afwerki, the Pretoria Agreement’s inclusion of the TPLF restored a mortal adversary’s standing and signaled a failure to neutralize a long-term threat.

Over the past several months, forces loyal to Debretsion Gebremichael have seized control of key towns and administrative centers, including Mekelle (The capital of Tigray). Eritrean intelligence allegedly played a covert role in supporting these operations, not to bolster Tigray’s autonomy, but to undermine the federal government and destabilize the postwar peace framework. Debretsion’s faction has acknowledged holding talks with Eritrean officials, framing them as efforts to improve regional ties, however internal critics allege these meetings served a more covert, political agenda.

What began as a localized rebellion has expanded. For Addis Ababa, this is no longer just an internal power struggle, it is a foreign-fueled conflict unfolding on home soil. The Tigray crisis, thought to be paused by the Pretoria Agreement, now risks reigniting entirely, and Eritrea is well-positioned to exploit the chaos. By backing Debretsion’s faction or stoking unrest elsewhere, including reportedly supporting the Fano militia in Amhara (the region bordering Tigray to the south), Asmara can keep Ethiopia destabilized without firing a shot. Meanwhile, should Ethiopia pursue military action over Red Sea access, the battlefield will not remain in Tigray or Amhara. It will cross into Eritrea, setting the stage for a full-scale war between two hardened adversaries, with regional consequences neither can fully control.

a region rearranged

The conflict is no longer bilateral. Eritrea has drawn closer to Egypt, long hostile to Ethiopia’s Grand Renaissance Dam, which it sees as a threat to its existential water security. Following Ethiopia’s controversial port deal with Somaliland, Egypt responded by deepening military and diplomatic ties with Somalia, including arms deliveries and a defense pact. Cairo left little to interpretation: it will back any actor willing to contain or confront Ethiopian influence. Ethiopia, for its part, has tightened its alliance with the United Arab Emirates, whose drone support and financial aid were pivotal during the Tigray war. Saudi Arabia, too, has edged closer to Eritrea amid concerns over Red Sea stability. While not a formal proxy conflict, the Horn of Africa is now a theater of intersecting ambitions, where alliances are shaped less by loyalty than by opposition.

The region’s power balance is shifting fast. In Sudan’s civil war, Eritrea has thrown its weight behind the Sudanese Armed Forces, supporting eastern militias and reportedly deploying proxy fighters. Ethiopia and the UAE, meanwhile, are widely seen as backing the rival Rapid Support Forces, through arms transfers, drone shipments, and financial support. Sudan’s domestic conflict has morphed into an arena of indirect confrontation, shaped by foreign interests vying for leverage across Eastern Africa.

the escalation trap

Abiy may be bluffing, using military posturing to gain leverage in future negotiations over Red Sea access. But in a international climate where norms around sovereignty are eroding and territorial revisionism is increasingly normalized, bluffing can become belief. The risk is not just rhetorical overreach, it’s escalation. A military push toward Eritrea’s Assab port, once nearly unthinkable, now lies uncomfortably within reach.

Such a move wouldn’t legally invalidate the Pretoria Agreement since Eritrea was not a signatory, but it would undercut its core achievement: a framework for political stabilization. It would escalate the current standoff into a wider, open war, destabilize Ethiopia’s already fragile northern regions, including Tigray and Amhara (Possibly also Afar region, which borders Assab and could be drawn into the conflict) and reignite the Tigray crisis into a new, more volatile phase. In that scenario, Eritrea could exploit the unrest to deepen its influence through allied factions, turning Ethiopia’s internal instability into a battlefield for external ambitions. The result: a a layered confrontation nested within another, destabilizing not just Ethiopia and Eritrea, but the fragile strategic balance of the whole region even more.

Diplomacy is still possible, but the window is narrowing. Each day of deadlock hardens positions, increases risks, and makes a return to peace harder to imagine.

This is not just a regional standoff, it’s also a test to see whether a continent already fractured by war can absorb another breakdown. Ethiopia and Eritrea once stood as a case study in reconciliation. They may soon be another entry in the ledger of wars no one meant to start, and no one knows how to end.

Insightful read. I hope a solution is found before another war break outs.