why some nepalis want the king back

after years of dysfunction, some nepalis are looking backward. not out of loyalty, but frustration.

Last year I wrote this story. It was about the royal massacre in Nepal back in 2001. Crown Prince Dipendra allegedly killed his whole family. His father the king, his mother the queen, his brother, and several other royals, then shot himself.

Dipendra had wanted to marry someone his parents didn’t approve of. One night, drunk and furious, he snapped.

He didn’t die right away. He fell into a coma. And while he lay there unconscious, they actually declared him king.

He died three days later.

I’d been to Nepal before. And when I came across the story, it stuck with me, not because it was some grand metaphor, but because it was bizarre.

The idea that a crown prince could wipe out his entire family, supposedly over a relationship?

At the time, I thought it was just a piece of history. A violent footnote. Something the country had moved on from.

But over the past few months, people are on the streets of Kathmandu. Chanting for the return of the monarchy, asking for the king to save the country.

Which made me ask, why?

Why are people calling for the return of something that ended nearly two decades ago?

Has democracy really failed that badly? Has the system stayed broken for so long that even the old one looks better?

That’s what this article is about.

the monarchy didn’t collapse. It crumbled.

Nepal was already unraveling when the massacre happened. A civil war had been raging since 1996, with Maoist rebels fighting to topple the monarchy and replace it with a communist republic.

When Crown Prince Dipendra allegedly killed his family, it didn’t end the monarchy. But it shattered whatever mystique it had left.

King Birendra, the one who died, was seen as a kind of father figure. Even if the system felt out of date, the man still had respect. But his brother Gyanendra? Not so much.

By 2005, Gyanendra suspended democracy and ruled by decree. That move sealed the monarchy’s fate. After mass protests, he stepped down in 2006. By 2008, Nepal officially became a federal democratic republic.

The rebels turned politicians. Elections were held. A new constitution was adopted.

On paper, Nepal had moved forward.

but on the ground, not much changed.

Since Nepal became a republic in 2008, it’s had 14 different governments. But power has mostly stayed in the hands of the same three men: Prachanda, KP Sharma Oli, and Sher Bahadur Deuba.

Prachanda led the Maoist insurgency, the actual civil war against the monarchy. Oli runs the UML, the Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist-Leninist), and Deuba heads the Nepali Congress, the country’s oldest centrist party.

They’re supposed to represent different ideologies. But in practice, they just keep cutting deals with each other, forming coalitions, collapsing them, switching sides. It’s politics as musical chairs. Just with the same three players on loop.

And the economy tells a similar story.

Sure, the GDP grew 5% last year. Tourism is bouncing back. Hydropower exports are climbing. Remittances hit a nine-year high.

But peel that back: a little over a quarter of Nepal’s economy comes from remittances, money sent home by Nepalis working abroad, primarily in Malaysia, Qatar, and the UAE. In 2023, these remittances totaled around $11 billion, accounting for approximately 27% of the country's GDP.

That’s not growth. That’s survival.

These workers often endure grueling conditions: long hours, extreme heat, and minimal labor protections. In Qatar, for instance, many laborers have faced excessive working hours, non-payment or delayed payment of wages, and crowded, unsanitary living conditions . The psychological toll is significant, with studies indicating that Nepalese migrant workers experience mental health challenges linked to their working and living conditions.

Many take on substantial debt to secure these jobs, only to find themselves trapped in exploitative situations. Some never return. Others come back injured, financially depleted, or unable to work.

Yet the country relies heavily on this income. Remittances keep families afloat. It props up the economy and papers over the fact that, inside Nepal, there just aren’t enough real opportunities.

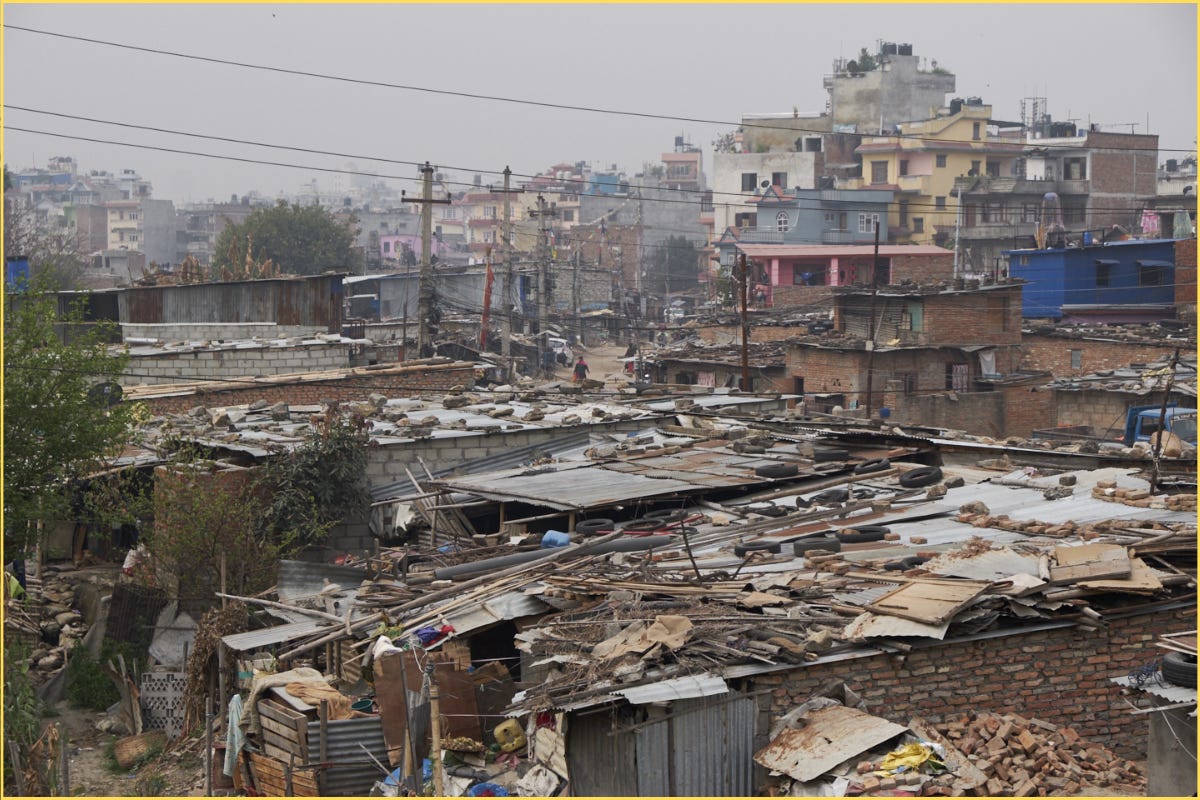

Jobs are scarce. Prices are up. Big infrastructure projects keep getting delayed. Corruption is baked in.

So even when the numbers look good, most people don’t feel it. Because for them, not much has actually changed.

and then there’s the giants next door.

Nepal’s stuck between two powers, India and China. And now, with the U.S. cutting back aid, it's feeling even more exposed.

It’s not that Nepal’s being invaded. It’s that it’s being pulled in two directions.

Nepali leaders try not to pick a side. They make deals with both India and China, but avoid fully committing to either, afraid that leaning too far in one direction will cost them with the other.

The result? Foreign policy becomes a balancing act. Domestic priorities stall. And to a lot of Nepalis, it feels like the country isn’t really steering itself anymore.

so why the king?

The protests aren’t about nostalgia for a golden era. There wasn’t one.

Even under the monarchy, Nepal was poor. Rural areas were ignored. Corruption was still rampant.

But what people are responding to now isn’t memory, it’s frustration.

Gyanendra, the ousted king, is still alive. Still makes public statements about unity and in March, after one vague speech, thousands showed up to the airport chanting for his return.

A lot of the energy is coming from young people, not the generation that lived through the monarchy, but the one that grew up after it ended.

To them, the monarchy isn’t about kings. It’s about the idea of stability. Of national pride. Of something that isn’t this endless, broken loop.

will the monarchy actually return? probably not.

No major party in power is backing it. There’s no legal path. Gyanendra is 77. His son, Paras, is widely seen as reckless and unfit.

There are smaller parties pushing for it, most notably the Rastriya Prajatantra Party (RPP), which won 14 seats in the last election and has been calling for a return to constitutional monarchy and a Hindu state.

Some speculate that Gyanendra could align with the RPP. But he’s stayed out of formal politics, and even if he joined, the party’s limited presence makes a full comeback unlikely without a broader coalition.

There are also whispers of support from across the border. Posters of India’s Yogi Adityanath have appeared at pro-monarchy rallies in Kathmandu, fueling speculation about quiet ideological backing from India’s Hindu right.

But the BJP hasn’t taken an official stance. And whatever cultural sympathies exist, there’s no clear indication of strategic support for restoring the crown.

This isn’t a coordinated movement to bring back the monarchy. At least not yet. It’s a protest without a plan. A pressure valve. A way for people to say: this isn’t working.

Nepal is not falling apart, it just can’t seem to move forward. Politics is tribal. The economy’s fragile. The future feels outsourced. And democracy, at least the way it’s been practiced, hasn’t delivered.

It’s not about bringing back the crown. It’s about the promise that replaced it, and how little of it people actually got.