zangezur and the shadow war against iran

a quiet infrastructure plan in the caucasus is lighting the fuse for a new regional war, drawing in turkiye, israel, the u.s., and iran

Hey everyone, it’s been a while.

Today I’m talking about the Zangezur Corridor, but if you think this is just some niche border project, you’re missing the big picture.

This is about the quiet formation of a new alliance: Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Israel. A geopolitical axis trying to reshape the South Caucasus and surround Iran. This isn’t speculation, it’s already in motion. The U.S. has now openly entered the game, with President Donald Trump brokering a so‑called “peace deal” between Armenia and Azerbaijan that grants Washington exclusive rights to develop and manage the Zangezur Corridor under a lease of up to 99 years, officially branded the Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity (TRIPP).

What was once a covert strategy is now becoming policy. At the center of this maneuver sits Armenia, Iran, and a region being set up for militarized infrastructure under the veil of trade and connectivity. The so-called corridor is no longer just a Turkish-Azeri project, it’s now a multi-vector push involving Israel, NATO, the U.S., and Gulf states looking to lock Iran out of the South Caucasus permanently.

the ceasefire that started it all

Let’s start with 2020. After the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War, a trilateral ceasefire was signed between Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Russia. The key clause? "All transport routes shall be unblocked." with Armenia guaranteeing safe passage and Russian FSB control over cross-border traffic

Russia imagined this meant reopening old Soviet-era rail lines, like the one through Yerevan to Nakhchivan. But Azerbaijan had a different plan. It demanded an entirely new route, one that would run through Armenia’s southern Syunik province and cut Armenia off from Iran. This is what they now call the Zangezur Corridor.

That route is about power, because it’s not just about cutting Armenia off from Iran or Iran off from the Caucasus, it’s also about cutting Iran's land bridge to Russia and giving Turkey a land bridge to Central Asia.

turan

You can’t understand the Zangezur push without understanding Pan-Turkism.

Pan-Turkism is an ultranationalist ideology rooted in the idea of uniting all Turkic peoples across a single geo-cultural and political space, stretching from Anatolia through the Caucasus, Central Asia, and all the way to western China’s Xinjiang region.

While it began as a 19th-century romantic nationalist project, today it has morphed into a hybrid of economic, military, and ideological ambition, championed most forcefully by Turkey under Erdoğan and by Azerbaijan’s Aliyev regime.

It’s backed by think tanks, media conglomerates, and transnational bodies like the Organization of Turkic States. Since the 2000s, Turkey has formalized Pan-Turkism into state policy, embedding military structures in Azerbaijan, launching joint officer education and NATO-aligned training programs, training Kazakh officers, funding infrastructure projects in Kyrgyzstan, and expanding Turkish-language education across Central Asia.

Even in Xinjiang, where China represses Uyghurs, Ankara’s criticism is muted, not only because of economic dependence on Beijing, but because Pan-Turkist ideologues view Xinjiang (or East Turkestan, in their lexicon) as the eastern frontier of a future Turkic world stretching from Istanbul to Urumqi. If Turkey loudly condemned China's abuses, it could jeopardize long-term infrastructure, energy, and cultural integration projects crucial to their pan-Turkic vision. Silence, in this case, isn't neutrality, it's strategic patience.

The Zangezur corridor isn’t just a route, it’s a cornerstone of this vision. A direct land bridge connecting Turkey to Azerbaijan, Central Asia, and beyond.

Armenia stands in the way of this vision. Syunik, in particular, is the final geographic and symbolic obstacle, a region in a Christian republic lodged between an expanding belt of Turkic power. To pan-Turkist ideologues, it's not just inconvenient; it's an aberration. A historical holdout that must be bypassed, encircled, or erased.

This isn’t about trade. It’s about empire.

the israel – azerbaijan – turkiye triangle

Azerbaijan provides Israel with nearly half of its oil, roughly 40%, maybe even 60% of Israel’s supply arrives via the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline and is shipped to Ashkelon. In return, Israel supplies Azerbaijan with drones, missiles, and surveillance systems. During the 2020 war in Nagorno-Karabakh, many of the systems used to target Armenian forces, including loitering munitions and advanced drone technologies, came straight from Israeli factories.

But the alliance goes deeper. Since the 1990s, Mossad has operated surveillance infrastructure inside Azerbaijan, which has served as a base for monitoring Iran and, at times, launching operations. In June, Israeli agents allegedly used Azerbaijani territory to conduct sabotage missions inside Iran as part of Operation Rising Lion.

Meanwhile, Turkey performs outrage over Gaza while continuing significant trade with Israel. In Mid-2024, Turkey announced a formal trade ban with Israel, including restrictions on 54 export categories such as steel, fertilizer, jet fuel, and construction materials. However, UN data later showed that Turkey remained Israel’s fifth-largest source of imports that year, with trade continuing through indirect channels and third-party intermediaries. Turkish goods like steel and agricultural products continued to reach Israeli markets, illustrating the strategic gap between Ankara’s rhetoric and its economic behavior. SOCAR, Azerbaijan’s national energy company, now holds a 10% stake in Israel’s Tamar gas field and recently made infrastructure connection deals that could extend from Azerbaijan through Turkey into Syria.

Despite public spats, Turkey, Israel, and Azerbaijan still work together when it comes to weakening Iran’s position. This is clearest in Syria. Turkey was not a bystander in the war, it had a clear plan to remove Bashar al-Assad. For years Ankara kept its border open for fighters, weapons, and supplies heading to opposition areas, then built a mini-state in parts of the north like Afrin, Azaz–al‑Bab, Jarablus, and Idlib. Turkish currency, schools, and police were put in place, and local militias were armed and rotated. The goals were simple: stop the PKK/YPG/SDF (Kurds), keep refugees on the Syrian side as leverage over Europe, grab influence up to Aleppo, and block Iran’s route to the Mediterranean. The talk about “safe zones” and “counterterrorism” hid the reality, demographic changes, militia control over trade and aid, and shelling that kept people displaced.

Israel’s actions lined up with Turkey’s not out of friendship, but shared interest. Israeli airstrikes hit Iranian and regime targets, which often helped Turkish-backed forces or slowed down Assad’s advances without Turkey having to fight directly. It was coordination without open admission, both hitting the same enemy from different angles.

Azerbaijan stayed out of the actual fighting but joined in politically and economically. It echoed Turkey’s anti‑Assad line, amplified anti‑Iran messages, and under Ankara’s cover began exploring energy projects linked to Syria. Azerbaijan recently signed a direct energy deal with Syria. Under the agreement, Azerbaijani gas will start flowing into Syria via Turkey this month, with initial deliveries increasing over time toward an expected 2 billion cubic meters per year. There has also been talk, still speculative, about future pipeline connections tying Syrian demand into Turkey’s grid, which could link with Azerbaijan’s export network and, in theory, allow flows to Israel via Turkey and Syria. In short: Turkey entrenched itself in parts of northern Syria, Israel kept striking Iranian and regime targets, and Azerbaijan positioned itself to benefit in the post‑war landscape through energy links, political alignment, and a shared narrative aimed at weakening Tehran without direct combat.

This coordination has extended into Lebanon as well. In Tripoli, a Sunni-majority city in the north, Turkey has ramped up its soft power operations by funding mosques, educational programs, Turkish cultural centers, and NGOs, some with open links to Turkish intelligence. Ankara’s investment in local Sunni leaders has raised concerns in Beirut and beyond. Simultaneously, Israeli airstrikes against Hezbollah positions in the south continue with increasing frequency despite a ceasefire, and there are reports of HTS factions in Syria eyeing northern Lebanon, potentially with Turkish backing. The convergence of these dynamics suggests a multi-pronged effort (Israeli, American, Gulf, and Turkish) to encircle and erode Hezbollah’s influence. Turkey brands its push as Islamic outreach or fraternal aid, but it functions as another strategic lever in the cold war against Iran’s axis in the Levant.

Together, Turkey, Israel, and Azerbaijan have become an operational geopolitical machine, linked through energy deals, military coordination, trade, and surveillance. Their strategies were first sharpened and proven in Armenia and then Syria. In 2020, the trilateral partnership was on full display as Israeli weapons, Turkish drones, and Azeri troops devastated Armenian defenses. Meanwhile, in Syria, all three states pursued coordinated but compartmentalized campaigns to weaken and eventually replace the Assad regime. Turkey empowered Islamist factions in the north, Israel repeatedly targeted Iranian and regime infrastructure from the skies, and Azerbaijan, less visibly, aligned its diplomatic and energy strategies to isolate Assad’s allies and position itself as a long-term stakeholder in Syria’s post-war reconstruction.

Iran, alarmed by the military coordination so close to its borders, has responded with an increasingly muscular presence, staging large-scale drills near the border with Armenia and accelerating defense cooperation with Yerevan.

After Bashar al‑Assad’s ouster in December 2024 and the rise of a transitional leadership in Damascus, Tehran’s Syrian anchor has weakened; in Lebanon, Israeli strikes and targeted killings have hit Hezbollah hard, constraining Iran’s most important regional proxy. Coupled with Armenia’s 2020 defeat, which consolidated the Turkey–Azerbaijan axis on Iran’s northern flank. Tehran faces a more precarious map than it has in years. Iranian officials denounce the proposed Zangezur corridor as a project that would sever Iran’s strategic access to the Caucasus (often portrayed in Tehran as backed by hostile powers), and they have warned that any change to internationally recognized borders would bring “serious consequences.” hinting at the possibility of military action if its access routes are cut off.

Georgia, meanwhile, is experiencing a political drift. Once a staunch Euro‑Atlantic aspirant, its current government under the ruling Georgian Dream party has moved closer to Moscow, adopting foreign‑agent laws and echoing Russian narratives. This has dulled Georgia’s criticism of Turkish and Israeli activity in the region, despite clear risks to its role as a transit hub. At present, the primary overland route between Azerbaijan and Turkey runs via Georgia, by road and the Baku–Tbilisi–Kars railway, and Azerbaijan’s crude exports to Israel transit Georgia through the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan pipeline. These corridors generate transit fees and spin‑off business for Georgian rail, roads, and logistics. Behind closed doors, officials in Tbilisi are wary: a functioning Zangezur Corridor could redirect a meaningful share of east–west freight and some energy flows away from Georgian territory, reducing transit revenues and diluting Georgia’s strategic leverage, and potentially upending the delicate balance it maintains between Russia, the West, and regional powers.

So far, the responses from both Tehran and Tbilisi remain mostly rhetorical. But with U.S. involvement in the corridor now official, and military coordination between Turkey, Israel, and Azerbaijan continuing to intensify, regional actors are entering a phase of strategic recalibration by repositioning forces, redrawing alliances, and preparing for a future in which the South Caucasus is no longer a buffer zone, but an active front.

However, cracks are showing. Erdogan’s calculated decision to avoid a full trade embargo on Israel over Gaza has already drawn domestic and regional criticism. But more significantly, reports suggest Israel has attempted to assassinate Abu Mohammad al-Jolani/Ahmed al-Sharaa, leader of HTS, current president of Syria, on at least three occasions last month. Al-Sharaa is essentially a Turkish proxy in Idlib. This suggests growing divergence over Syria’s future, especially with Israel reportedly favoring the creation of autonomous Druze and Kurdish zones, both of which would undermine Turkish and Iranian regional visions.

So while the alliance still stands, its internal contradictions are sharpening. And Syria, once a shared battlefield, may become the place where their interests start to clash.

back to the caucuses

In the South Caucasus, Armenia is pivoting toward the EU, Russia is slowly reasserting itself in the region after a temporary retreat, especially as the war in Ukraine begins to tilt more in its favor. Iran is digging in, and Turkey is arming for the next phase. Israel, meanwhile, is setting up deeper surveillance networks, and the Gulf states are investing in the infrastructure meant to drive this corridor forward. Everyone sees what's coming. The Zangezur Corridor is a fuse that is waiting to be lit.

But will the EU really help Armenia when the time comes? After all, most EU states are in NATO, and NATO already has Turkey who is aligned with Azerbaijan (Azerbaijan is also a major supplier of natural gas to Europe while Armenia’s trade volumes are far smaller and lack comparable strategic value). Brussels may offer economic aid, diplomatic support and maybe some military aid but no one is sending troops. Armenia risks becoming another Ukraine, encouraged to pivot West, but left alone when the blowback comes.

As for Pashinyan, he’s not exactly a unifying figure. Unlike Zelenskyy, whose pivot to the West was met with broad nationalist support, Pashinyan is increasingly isolated at home. His pivot toward the EU has sparked backlash from the Armenian Apostolic Church and wide swaths of the public who view his reforms as both culturally corrosive and strategically reckless.

This break with the Church is part of a deeper cultural and geopolitical realignment (as the church is seen as pro-Russia). Pashinyan has effectively abandoned Armenia’s historic alliances with Russia, leaving the country exposed at a time of growing regional hostility. There’s also rising suspicion among Armenians that Pashinyan’s government may have allowed or even facilitated the loss of Artsakh in 2023 as part of a broader Western integration plan, an accusation that continues to fuel protests and feed rumors of betrayal.

His approval ratings have plummeted, and discontent has now spread from traditionalists to nationalists to even parts of the Armenian diaspora. Pashinyan’s opponents accuse him of acting on behalf of Western interests, trading sovereignty and security for vague promises of modernization and EU alignment.

Unlike Ukraine, Armenia lacks the leverage that comes from Black Sea ports or strategic energy routes. What it has is geography and a vulnerable population trapped between regional empires, each playing a long game of influence.

the plan to break iran

This triangle — Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Israel — is now increasingly aligned in another shared objective: the containment and fragmentation of Iran.

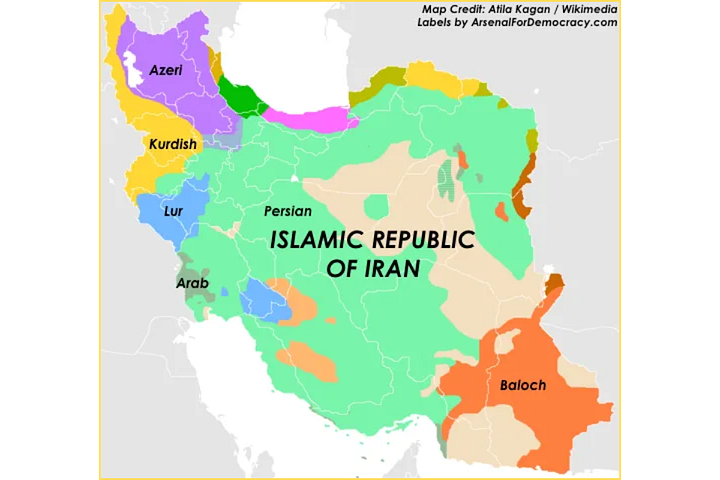

Israel’s long-term goal, often discussed in security circles, is to balkanize Iran, to break it into smaller, weaker statelets. One of the most convenient and plausible pressure points? South Azerbaijan. The northwestern region of Iran home to over 15-20 million ethnic Azeris. Many in the nationalist circles of Azerbaijan, and particularly among pan-Turkists in Turkey, view South Azerbaijan not as Iranian territory, but as occupied Turkic land. They dream of reunification, not unlike irredentist ambitions in other parts of the world.

This mutual interest binds them to Israel’s broader goal. For Israel, empowering Azerbaijani nationalism inside Iran creates internal friction and destabilizes Tehran from within. For Turkey and Azerbaijan, it’s an opportunity to expand influence, redraw borders, and lay claim to a pan-Turkic homeland that stretches into Iranian territory. Iranian officials have openly warned about this, accusing Baku of hosting Mossad and fomenting separatism. And they’re not wrong.

Over the past few years, Iran has arrested dozens of so-called 'pan-Turkic' “activists” inside its borders. Meanwhile, Israel has increasingly used Azerbaijani territory as a launchpad for intelligence and sabotage missions. Mossad operations staged from Azerbaijan include cyber attacks, assassinations of Iranian nuclear scientists, and the extraction of physical documents from Tehran's nuclear archive, as revealed by former Prime Minister Netanyahu in 2018. More recently, Israel's Operation Rising Lion included drone strikes and targeted killings, with Israeli agents reportedly entering Iran via Azerbaijan. Baku has rhetorically aided this campaign by amplifying narratives about South Azerbaijan's 'liberation' and hosting anti-Iranian dissident conferences.

So while on paper Azerbaijan and Iran are neighbors with diplomatic ties, in reality Baku has become a frontline outpost for one of Israel’s most aggressive covert strategies, aimed squarely at Iran. At the same time, Turkey leverages this setup to push its ideological vision of pan-Turkism, using Azerbaijan as both a military ally and a cultural springboard. The result is a double-edged offensive: one edge seeks to fracture Iran from within, the other to extend Turkish influence across historical Turkic lands, including into Iranian territory.

Contrast this with Iran’s internal reality. While South Azerbaijan is ethnically Azeri, most of its population is deeply integrated into Iranian society. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei is himself partly ethnic Azeri, and Iran’s president, Masoud Pezeshkian, is also of Azeri descent, which complicates the pan-Turkic narrative of 'occupied' Turkic land. In fact, Azeris occupy high-ranking positions in Iran’s political, military, and clerical institutions. There is no meaningful separatist movement in South Azerbaijan; the majority of Iranian Azeris identify as Iranian nationalists, not pan-Turkic irredentists.

Azerbaijani culture in Iran is deeply rooted, historic, and thriving. Iranian Azeris contribute significantly to the country's literary, artistic, religious, and political life. The language is widely spoken, traditions are preserved, and cultural life remains vibrant, particularly in cities like Tabriz. By contrast, the Azeri identity promoted by Baku is a modern, Soviet-era construction designed to align Turkic identity with state nationalism. Most Iranian Azeris view it as artificial and culturally foreign. The irredentist narrative peddled from Baku doesn’t resonate because it has no authentic cultural foundation. In fact, there are more ethnic Azeris living in Iran (15-20m) than in the Republic of Azerbaijan itself (10m). Historically, the territory of the modern Azerbaijani state was merely a northern province of a broader Iranian Azerbaijan. This deep historical and demographic reality underscores why Iranian Azeris see themselves as fully Iranian, with cultural and political identities distinct from Baku's pan-Turkist project.

so what’s next?

The Zangezur Corridor is a microcosm of 21st-century imperialism. Disguised as infrastructure, marketed as connectivity, and enforced through soft power, military pressure, and proxy manipulation. It represents a new chapter in the Great Game, this time played not just by old empires like Russia or Britain, but by regional actors like Turkey and Israel.

Armenia finds itself at the center of this storm. Politically confused, militarily weakened, and internally divided. Pashinyan’s Western pivot may reflect the aspirations of part of Armenia’s population, but it has alienated large segments of society and left the country dangerously exposed. Meanwhile, Iran is ringed by adversaries, facing a coordinated campaign to fracture its periphery, inflame internal divisions, and sever its influence in the Caucasus and the Levant.

Azerbaijan, emboldened by Israeli weapons and Turkish support, is no longer acting like a small energy emirate, it's behaving like a regional power-in-waiting. Turkey sees the corridor as a keystone in its civilizational revival project. And Israel, ever pragmatic, sees opportunity in every friction point, every fault line that can be activated to weaken its adversaries.

What happens next is uncertain. A wider war with Armenia or Iran is possible, but the U.S.-brokered Zangezur Corridor, rebranded as the “Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity”, has already shifted the region’s balance. Its mere proposal has exposed agendas, hardened alliances, and dragged the South Caucasus into the middle of global power politics.

Iran is positioning itself to fight back. Armenia’s leadership appears ready to accept the new order, but polls show most Armenians distrust Pashinyan and view Iran as their strongest security partner.

Whether Armenians accept this reality or actually push back, and whether Iran can turn its vow to resist into real leverage, will determine if the “Trump Route” is a permanent artery or a doomed experiment

The fuse is lit. In the South Caucasus, standing still is just another way of losing ground.