bangladesh overthrew a dictator. now it must dismantle the state she built.

sheikh hasina is gone. but the system that made her possible still holds power.

Ten months after the uprising that forced Sheikh Hasina into exile, Bangladesh finds itself in a perilous limbo. The interim government has banned her party, arrested thousands, and launched what it calls a process of justice. Yet in the courtrooms of Dhaka, where lawyers face harassment and thousands remain detained under sweeping charges, there are growing concerns that the revolution is echoing the repressive practices it once opposed. Rather than prioritizing systemic reform, the interim regime appears increasingly focused on retribution. Rhetoric demanding severe punishment for former regime figures, though historically rooted in calls for justice, now risks blurring the line between accountability and vengeance. The urgent question is whether Hasina's ouster marked a true break from autocracy, or merely a transfer of its mechanisms.

The stakes are not just about who rules. They are about whether the machinery of repression that upheld Hasina's regime will be dismantled, or simply rebranded.

the regime that fell

For fifteen years, Sheikh Hasina ran one of South Asia's most durable autocracies. Her rule fused economic liberalization with political repression. Under the banner of secular nationalism, Hasina consolidated power through patronage, surveillance, and the brutal efficiency of forces like the DGFI and the Rapid Action Battalion. Thousands were disappeared. The judiciary was weaponized. Elections were reduced to theater.

But the autocracy was as much economic as political. Bangladesh's so-called "development miracle", lauded by donors and foreign investors, relied on hyper-exploitation: garment workers earning poverty wages, rural migrants packed into slums, educated youth locked out of formal employment. GDP soared. So did inequality. The top 1% enriched themselves via real estate, state contracts, and foreign partnerships, while the bottom 50% remained one cyclone or medical bill away from destitution.

Religious minorities, including Hindus, were instrumentalized. While elite Hindus in finance and academia gained upward mobility through Awami League patronage, poorer co-religionists in rural and border regions were often dispossessed or tokenized. The regime preached secularism when useful, and looked away when violence served its interests. Class, not creed, determined safety.

The Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), long the country's official opposition, has consistently failed to offer a credible structural alternative. It’s still dynastically led by Khaleda Zia, aged 79, who served multiple terms as prime minister and her son Tarique Rahman. the party continues to veer between populist agitation and backroom alliances with entrenched elites. Despite its rhetorical opposition to the Awami League, the BNP shares many of its features. Dynastic control, elite patronage networks, and a record of using the state to suppress dissent while enriching allies. Its resurgence may galvanize loyalists, but it risks reinstalling the same elite consensus that helped sustain Bangladesh's political stagnation for decades.

And then there is the military. More than a kingmaker, it is an economic and political force. Through enterprises in construction, finance, insurance, real estate, and hospitality, managed by entities like Sena Kalyan Sangstha and the Army Welfare Trust, it maintains vast commercial interests and financial autonomy unmatched by civilian institutions. Its push for early elections, framed as a step toward stability, is less about democratic transition than about securing its influence. In this, Bangladesh’s military closely resembles Pakistan’s: both countries have powerful armed forces that run vast business empires and use their economic influence to steer politics behind the scenes, all while maintaining the appearance of civilian rule. Without deep structural reform, such elections would only redecorate the same regime architecture.

This is the template of South Asia's development autocracies: economic growth, elite wealth, and political control, anchored in militarized security states. While the degrees and dynamics vary, parallels can be found across the region. India, under the BJP, has combined pro-business economic policies with a political agenda centered on Hindu dominance, while becoming less tolerant of dissent and weakening democratic institutions. Sri Lanka’s previous government built flashy infrastructure while racking up unsustainable debt and widespread corruption. Even after a change in leadership, powerful military and business elites still hold significant control. Nepal’s ruling parties have repeatedly made deals that keep power within the same elite circles, ignoring deeper reforms. Many citizens, frustrated with corruption and instability, have even begun calling for a return to monarchy. These trends, where elites stay in power, governments rely on police and military power to silence critics and suppress protests, and democratic freedoms shrink, are worryingly common, even in countries that claim to have left authoritarianism behind.

the july uprising

What disrupted this consensus was not a party or a foreign power, but a coalition from below. Triggered by a civil service quota dispute, the July uprising became a class rebellion. Public university students, slum dwellers, underemployed youth, and rural migrants flooded the streets with demands for change and justice.

The Anti-Discrimination Students' Movement, secular and fiercely independent, led the charge. Its leadership, drawn from public institutions and rural families, articulated demands for dignity and equity. Their slogans were not religious, but revolutionary: "New Bangladesh," "No to Fascism," "Inclusion Now."

Yes, Islamist groups joined the protests, including Jamaat-e-Islami, but they were peripheral to the uprising's core. Their controversial participation revealed the breadth of anti-regime sentiment but also generated friction. Meanwhile, Hindu, indigenous, and secular activists helped anchor the uprising in pluralist principles. Garment workers and day laborers expanded its reach. This was a movement of the excluded: fractured, but radical in imagination.

What bound these groups together were not just slogans, but a coherent list of structural demands: dismantling the DGFI and RAB; ending impunity for security forces; repealing laws like the Digital Security Act that criminalize dissent; reversing privatization in education and healthcare; instituting living wages, union rights, and labor protections; restoring judicial and electoral independence; and devolving real power to local government. These were demands for a different kind of state. And they remain the revolution's unfinished agenda.

india's stake

Hasina's fall unsettled more than Dhaka. For Delhi, it was a geopolitical jolt. India, once lauded for supporting Bangladesh's 1971 liberation, had become Hasina's staunchest backer, defending her repression in the name of regional stability. Her exile exposed the cynicism of that alliance.

Delhi’s security establishment framed the uprising as Islamist chaos. A narrative pushed aggressively by far-right Indian media from early 2024, as protests in Bangladesh escalated. This narrative peaked this week, when pro-BJP outlets circulated a video of a purported Lashkar-e-Taiba commander claiming involvement in the protests, despite its dubious authenticity. Hasina’s son, Sajeeb Wazed, amplified this video, portraying the uprising as a jihadist conspiracy. But this wasn’t an isolated tactic. Indian media also circulated inflated reports of anti-Hindu violence, allegations of a mass Hindu exodus, and dire predictions of national collapse under the interim regime. These stories, often unsubstantiated or based on manipulated content, served a dual purpose: to delegitimize Bangladesh’s revolution, and to reinforce the BJP’s own domestic narrative of Hindu victimhood and regional siege. Independent investigations and rights monitors have found no credible links between the July movement and jihadist networks. The uprising’s secular, working-class, and student-led leadership stood in stark contrast to the specter of extremism invoked by Delhi.

India’s concern for Bangladesh’s minorities, particularly Hindus, is not unwarranted however. But its credibility is undercut by its own slide into Hindu extremism. The BJP's domestic record includes lynchings, disenfranchisement, pogroms of Muslims and that makes its warnings about extremism elsewhere ring hollow.

To India, Bangladesh is more than a neighbor, it’s a strategic buffer. It absorbs migration and political turbulence that might otherwise inflame India’s sensitive northeast. Under Sheikh Hasina, Dhaka played both sides: partnering with India on counterinsurgency and security, while welcoming Chinese investments in signature projects like the Payra Port and Karnaphuli Tunnel. But Hasina’s fall, and the unpredictability of what comes next, has rattled New Delhi. India fears Dhaka could tilt too far toward Beijing, especially after China’s recent $2.1 billion pledge, or rekindle ties with Islamabad, as signaled by the first diplomatic talks between Bangladesh and Pakistan in over a decade. The broader anxiety is chaos: that Islamist resurgence, great-power jockeying, or state fragility in Bangladesh could spill across the border, destabilizing India’s eastern flank or India as a whole in general.

China’s engagement, by contrast, has matured from opportunistic to entrenched. Under Hasina, Beijing offered capital without governance strings, reinforcing her centralized grip. Under the interim government, it’s doubling down, financing industrial zones, promising interest rate relief, and embedding itself in Bangladesh’s economic architecture. The U.S. continues its careful calibration: “wary of rights abuses” but dependent on Dhaka for counterterrorism and Bay of Bengal access. Pakistan, while officially mute, saw its media cover Jamaat-e-Islami’s legal revival with notable attention, an echo of the historical affinity between Pakistan’s political elite and South Asian Islamist movements, rather than overt endorsement.

the interim and its limits

Into this vacuum stepped Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus, chosen to lead the interim regime. Once hailed internationally for pioneering microfinance, Yunus now finds himself facing growing criticism at home. His administration has outlawed the Awami League, detained thousands, and continued using many of the same laws and institutions that upheld Hasina’s rule, now turned against her and her supporters.

Yunus argues that these measures are temporary, meant to lay the groundwork for a real democratic transition. But they also expose how much of the old regime's machinery remains intact. Reforming Bangladesh’s political architecture isn’t just about good intentions, it means confronting powerful, deeply rooted systems. The Election Commission still includes officials from the Hasina era and has been accused of rigging votes and limiting access for opposition groups. The judiciary, especially at the top, has often served the executive, issuing politically convenient rulings instead of upholding constitutional standards. Key security agencies like the SB, DGFI, etc remain largely untouched, continuing to surveil and intimidate political opponents with little oversight. While the Digital Security Act was repealed in 2023, its repressive legacy lives on through the Cyber Security Act and draft laws that still criminalize dissent and threaten press freedom. Voter lists are unreliable, and the process to register new parties remains complicated, shutting out many grassroots and minority movements. Local election commissions are underfunded and weak, unable to safeguard fair elections at the community level. Without overhauling these structures, any election risks reinforcing the very system the revolution sought to dismantle.

To hold elections under these conditions would not be a return to democracy. It would be a reinstallation of the same system, dressed in procedural legitimacy. The military wants a vote to stabilize the field on its terms. The BNP wants a shortcut to power. The international community wants closure. But rushed elections without structural overhaul would betray the uprising’s core demands and likely foreclose the possibility of deeper transformation.

youth politics and structural vacuum

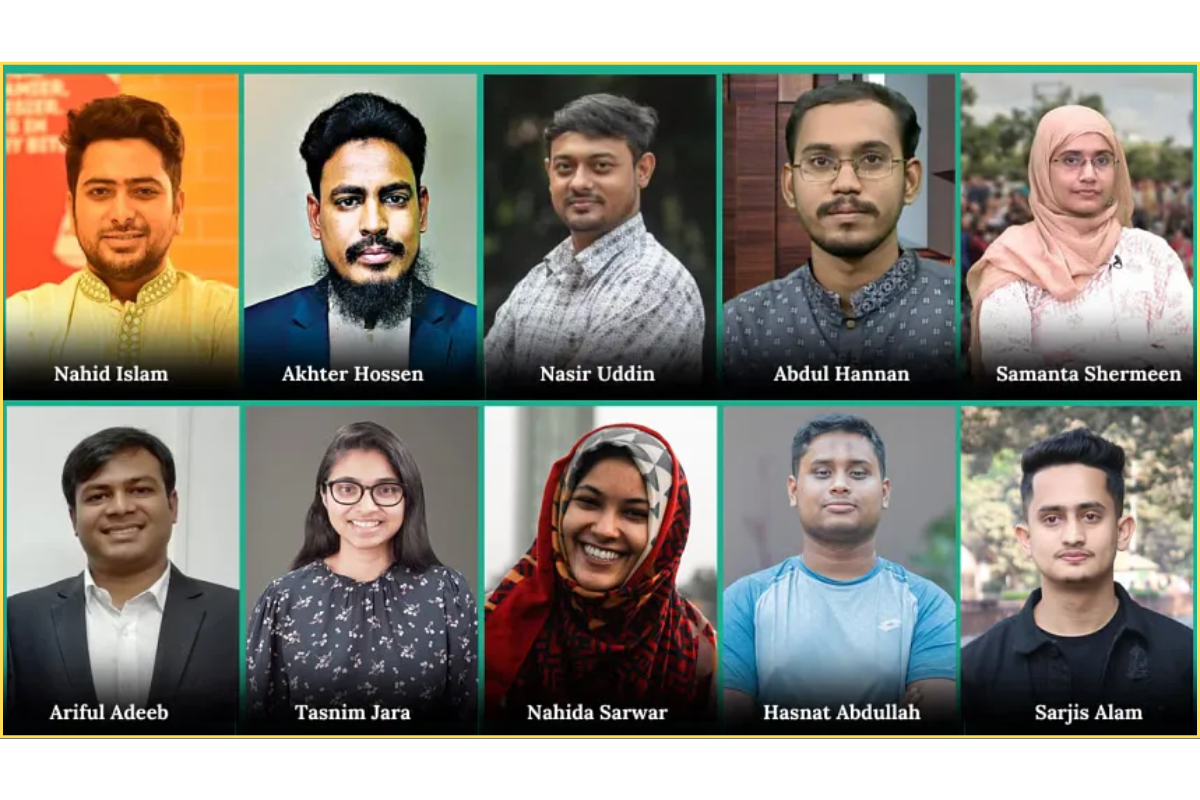

The most promising development is also the most fragile. The National Citizens’ Party (NCP), born from the student-led uprising, has widespread support but lacks the structure of a major political force. It distances itself from both the AL and BNP and calls for rewriting the constitution, empowering local government, and tackling inequality. But without strong connections to labor groups, rural networks, or clear policy plans, it risks becoming either a well-meaning but ineffective group or getting absorbed by the old elite system.

Still, the NCP reflects a broader global trend. From Chile to Serbia and Türkiye to Thailand, young people are pushing back against entrenched power with demands for fairness, representation, and dignity. Like them, the NCP represents a generation fed up with elite failure, but it must turn that anger and hope into lasting political strength.

Already, it has forced older parties to take notice of issues they long ignored. But its survival depends on whether it can withstand sabotage, international meddling, and the internal challenges of building something new. The revolution’s future rests on whether the NCP can move from protest to power, without losing its soul.

a regional beacon or recycled autocracy?

South Asia is in flux, but not in retreat. The era of development-backed authoritarianism is showing signs of strain, but each country follows a different path. In Sri Lanka, the left-leaning NPP is attempting to channel post-crisis street anger into constitutional and economic reforms, though constrained by IMF pressures. Nepal, while maintaining a multiparty democracy, remains dominated by elite consensus politics and has seen a surge of pro-monarchy demonstrations demanding the restoration of the royal family. The Maldives oscillates between democratic elections and centralized presidential power, with recent calls to fix its flawed presidential system. Pakistan’s military continues to control politics from behind the scenes, recently cementing its dominance with the elevation of its army chief to field marshal. India fuses rapid economic growth with an increasingly authoritarian Hindu nationalism that curtails dissent and weakens institutional independence. Myanmar is in a state of civil war, with armed resistance and ethnic militias confronting a junta that now controls less than a quarter of the country. Afghanistan remains under Taliban rule. Strictly authoritarian, governed by religious decree, and isolated globally. Even Bhutan, often praised for its Gross National Happiness model, faces renewed scrutiny for its limited political space and long-standing repression of minorities. Across the region, states maintain the facade of democracy, while elite networks retain power through coercion and control. What happens in Bangladesh won’t just test its revolution, it could determine whether the region begins to crack this entrenched model.

If Bangladesh is to be more than a cautionary tale, it must dismantle the infrastructure of autocracy, not just switch out its operators. That means dismantling the machinery of state repression. It means restoring the judiciary’s independence from military and party control. It means scrapping laws designed to muzzle dissent. It means real wealth redistribution, not trickle-down promises. It means shifting power to the local level and away from Dhaka’s dynasties. And it means holding war criminals accountable, across all factions, not just the politically convenient ones.

But the urgency is compounded by another danger. Even if Islamist groups like Jamaat-e-Islami represent a small portion of the population, they are well-organized, deeply motivated, and not afraid to impose their vision of a "better" Bangladesh. If the secular revolution fails to deliver meaningful reforms, if justice is delayed, if inequality persists, if elite impunity remains, then disillusionment may drive people toward theocratic alternatives that promise swift, uncompromising change. This revolution has only one shot to prove that democracy and justice can coexist. If it falters, the vacuum may not be filled by another autocrat, but by something far more dangerous.

None of this will happen without a fight. The military seeks rapid stabilization to safeguard its interests. The BNP aims to reclaim power without disrupting the status quo. Foreign powers want reliable allies, not radical change. And India, once celebrated as Bangladesh's liberator, now prioritizes control over solidarity, favoring managed borders and regional leverage over meaningful transformation.

Bangladesh has already toppled a dictatorship. Whether it can now build a republic worthy of its revolution is the next test. The clock is ticking.