chad is helping fuel sudan’s war. its own crisis may be next.

a military regime propped up by gulf money and strategic silence is enabling a paramilitary campaign next door. but the collapse that looms may be its own.

In Sudan’s civil war, much of the world sees chaos: rival generals, scorched cities, a spiraling humanitarian collapse. But across the border, one of the systems sustaining that chaos sits in quieter ruin.

Chad, a fragile military regime run by generals, oiled by foreign cash, and caught in the long shadow of postcolonial entanglements, has become a logistical spine for Sudan’s war machine. Weapons routed from the United Arab Emirates to Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces (RSF) pass through Chadian soil, landing in desert airstrips dressed as humanitarian aid. The world condemns the RSF’s atrocities. It largely ignores the corridors that sustain them.

But Chad is more than an accessory to conflict. It is a state not collapsing, but never cohering, functioning just enough to persist, but never enough to evolve. A regime kept standing not by its people, but by the power it offers others. Not with the spectacle of rival generals, but with the absence of every pillar that ever suggested a semblance of order: schools that barely functioned, clinics that rarely have medicine or doctors, a government that feeds on foreign loans and delivers repression in return. What it enables abroad, it reflects at home.

This is not a new story in the Sahel, but Chad’s version carries distinct dangers. The country is a keystone in the region’s precarious security architecture, a former French garrison now refitted for Emirati strategy. Where once Paris backed the Chadian regime with troops and money, today it is Abu Dhabi supplying arms, funds, and political cover. The exchange is simple: Chad offers access and obedience; the UAE provides survival. The regime stays upright not because it governs well, but because it serves.

For years, France treated Chad as its last reliable military partner in the Sahel. That ended in November 2024, when the Chadian junta quietly terminated its defense pact and sent French troops packing. Into the vacuum stepped the UAE. Since then, Emirati cargo flights have landed in Amdjarass, near the Sudanese border, supplying weapons to the RSF, according to UN investigators. Chad, willingly or not, has become a link in a war supply chain.

When Sudanese General Yasser al-Atta threatened to bomb Chadian airfields in March, accusing N'Djamena of aiding the RSF, it wasn’t mere theater. It marked a fracture built not on old proxy dynamics but on a new dynamic. In the 2000s, Chad and Sudan traded insurgencies in a deadly tit-for-tat. That ended with Omar al-Bashir's fall. Since then, Sudan has ceased meddling in Chadian politics. What remains is not reciprocal warfare but a transactional imbalance: Chad is the conduit, Sudan the target. The RSF’s lifeline runs through Chadian territory, but it’s Sudan that burns (For now at least.)

For Chad’s regime, that imbalance isn’t accidental, it’s strategic.

Chad’s rulers know this game. They play it not out of ideology, but out of necessity. Mahamat Idriss Déby, who took power after his father’s death in 2021, leads a junta cloaked in promises of reform but governed by repression. The promised 18-month transition has stretched past four years. A constitutional referendum in 2023 reshaped the political order in the junta’s favor. Elections followed, marred by boycotts, opposition crackdowns, and the killing of Déby’s cousin and rival, Yaya Dillo, in a murky security raid. Déby’s other main opponent, Succès Masra, was appointed transitional prime minister in late 2023 as part of a supposed reconciliation process, then placed second in the 2024 vote. He contested the outcome, claiming victory. By early 2025, he resigned.

To the international community, Déby offers the same pitch his father perfected: stability, compliance, counterterrorism. In return, the regime receives money, arms, and impunity. The UAE has reportedly provided $1.5 billion in loans, armored vehicles, and military trainers. Russia has begun courting Déby, too, hosting him in Moscow. Turkey, meanwhile, has deepened its ties through security cooperation, infrastructure projects, and religious diplomacy. France, while formally sidelined, still haunts the landscape, its companies entrenched in oil, food, finance and logistics, its past complicities unresolved. In 2023, Chad nationalized ExxonMobil’s assets in the Doba basin, blocking their sale to a British firm and reasserting control over a key source of revenue. It was a rare flex of sovereignty, one that raised hopes of greater economic autonomy. But managing these oil fields requires expertise and capital that Chad may struggle to marshal without foreign support, leaving the gains of nationalization uncertain.

Oil remains the backbone of Chad’s economy. It accounts for over 75 percent of export earnings and a significant share of government revenue. But the wealth does not trickle down. About 44 percent of Chadians live in extreme poverty. Most of the oil wealth flows outward, captured by foreign firms or siphoned off by elites.

The foundations of the country were never built to last. Every regime, including Déby’s, has governed with the same blueprint: repression, patronage, and ethnic exclusion. What stability exists never holds. It always collapses back into the same pattern: a new regime, a different face and ethnic group, but the same broken design, one Western powers continue to praise as stable. Corruption is endemic. A presidential aide was jailed for embezzling $15 million. A French inquiry has been opened into Déby himself. In 2023, a Mediapart investigation alleged he spent over €900,000 on luxury clothing at a Paris tailor. The presidency denied the claims, attributing the purchases to an adviser and suggesting political motives behind the report. But even if the claims are inflated or politically driven, they aren’t implausible, and that optics alone say plenty.

Prospects for young people are bleak. The median age in Chad is 15. The education system is abysmal, with a literacy rate hovering around 27 percent, one of the lowest, if not the lowest in the world. The health system also ranks among the world’s worst, with maternal and child mortality rates among the highest globally. The military, dominated by a narrow Zaghawa elite, remains the regime’s spine, but its grip is loosening.

In the north, Zaghawa-led rebel groups like FACT and UFR continue low-level insurgencies, however its more recalibration than revolution. In the south, state absence has bred a patchwork of criminal networks. Some are linked to cross-border operations with Cameroon and the Central African Republic. Others emerge from local grievances. These southern zones, home to Christian and animist groups like the Sara, have long been excluded from national power. Around Lake Chad, Boko Haram endures, exploiting porous borders and state neglect. In January, gunmen attacked the presidential palace. The government dismissed it as amateurish. Nineteen people were killed, including 18 assailants and one member of the presidential guard. The seriousness of the target, and the fact that President Mahamat Déby was reportedly inside at the time, suggests this was far more than a minor incident.

And yet the regime endures. Not because it delivers governance, but because it functions just enough to serve foreign interests. That’s the deeper contradiction: Chad is broke in every way that matters to its citizens, but flush with foreign deals that keep its elite secure. The UAE dominates recent headlines, but Chad also draws security assistance from the United States, development funds from the European Union, and, more oddly, loans and a military presence from Hungary. It is an alliance that makes little sense on paper, but perfect sense in the shadow trade of modern geopolitics, where repression is turned into currency: a way to gain money, weapons, and political favor. Chad’s strategic value lies less in what it creates than in what it contains: migration, militants, and mess. That, more than anything, is what sustains its regime.

The RSF, once the Janjaweed, massacred Zaghawa communities during the Darfur conflict and continues to target non-Arab groups today. Between late 2024 and early 2025, the RSF burned more than 80 Zaghawa villages and killed hundreds, according to UN monitors. By ethnic logic, they should be Chad’s enemy. But logic dissolves in the face of transactional survival. Today, the RSF is armed via routes that pass through Zaghawa territory. Old wounds shelved. New deals struck.

Climate change makes everything worse. Droughts displace pastoralists, some of whom (Chadian Arabs) have joined the RSF. Who’s to say they won’t one day turn their guns back toward Chad? The roots of one war feed another.

Chad is not Sudan. But it’s drifting along a similar axis of decay. Less a mirror, more a mosaic of the Sahel’s fragilities: the junta politics of Mali and Burkina Faso, the abandoned peripheries of Cameroon and northern Nigeria and Sudan. But where Sudan had ministries, a political class, an urban center with civic memory, Chad never built really built any of that. It was skeletal from the start, a regime without real bureaucracy, a capital without real statehood. If Khartoum once gestured toward national coherence, however tenuous, N'Djamena was never asked to. Chad has been ruled not like a country with a capital, but like a frontier: managed for access, not allegiance; stability, not stewardship. It is not Sudan in miniature. It is Darfur, scaled to the size of a nation.

Sudan collapsed into war. Chad may not follow that exact path. But it is drifting toward its own form of breakdown, not with the violence of rival armies, but with the decay of a state that never fully formed. It survives only because others find it useful. And in that exchange, the institutions that might bind a state, like ministries, schools, clinics, and trust, were never more than gestures. Flimsy scaffolding meant to signal governance without delivering it.

The question isn’t whether the nation collapses. It’s whether there was ever a real state to begin with. In Chad, power doesn’t changes through elections; it is seized, handed down, or staged as reform. First coups and now successions, each presented as a break from the past, each reproducing it. The faces may change. The logic does not. Foreign patrons rotate, promises are recycled, but the machinery remains: fragile, extractive, built to last just long enough to serve someone else’s purpose.

As Sudan’s war radiates outward, Chad’s complicity deepens and so does its fragility. This is no longer a case of a neighboring regime quietly enduring. It is one increasingly entangled, increasingly unstable. The danger is not only what Chad enables across its border, but what that entanglement reveals about the vacuum within. The next collapse may not come with spectacle, but with slow, strategic rot. And when it does, it won’t stay contained.

To get the full picture of the UAE’s role in Sudan’s war, check out my investigation for The Africa Review:

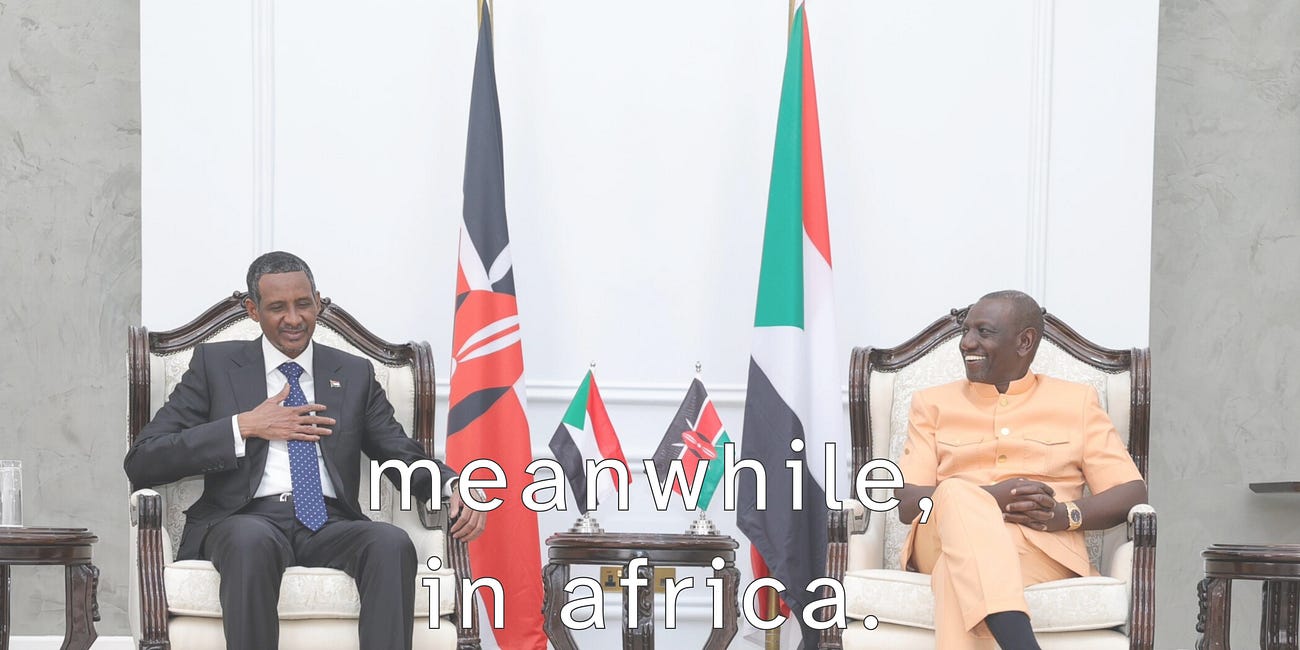

President Ruto insists Kenya’s role in Sudan is strictly diplomatic. The facts suggest otherwise. Read the full investigation:

kenya’s corridor of complicity

President William Ruto is selling his Sudan policy as peace diplomacy. But Kenya’s embrace of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), the militia accused of genocide in Darfur, has less to do with peace and …