the fall of tanzania’s reformist president

the illusion of reform: how tanzania’s promise of change ended in blood and silence.

Five months ago, the story was already written between the lines. Samia Suluhu Hassan had gone from reformer to warden. Opposition figures were in prison or in exile, and Tanzania’s ruling party, Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM), was once again governing by fear. Still, there was a thin hope that the October 2025 election might reopen the political space she had once promised to defend. It didn’t. It closed it for good.

Read my previous piece from five months ago to see how the warnings of this moment were already unfolding:

tanzania’s crackdown has a feminist face

Last month, Kenyan activist and photojournalist Boniface Mwangi and Ugandan lawyer and journalist Agather Atuhaire were arrested in Dar es Salaam. Where they had traveled to attend the court hearing …

the coronation in blood

On October 29, Tanzanians went to the polls under the watch of soldiers. The contest was predetermined: the main opposition party, Chama cha Demokrasia na Maendeleo (CHADEMA), was banned for allegedly refusing to sign the electoral code of conduct, and its leader Tundu Lissu was in prison facing treason charges. Other parties like ACT–Wazalendo (Tanzania’s second-biggest opposition party) saw their candidates disqualified on technicalities, leaving only a handful of minor, pro‑CCM figures on the ballot. Basically spectators in a pre‑decided race. Independent monitors were turned away from polling stations. Within hours, results trickled out on state television showing Samia ahead in every district, rural or urban, with margins that defied arithmetic. By nightfall, the streets of Dar es Salaam began to fill, not with celebration, but with barricades.

Protests first broke out across Dar es Salaam, Tanzania’s largest city and commercial hub. Demonstrations began as results showed Hassan’s overwhelming lead, spreading quickly through several neighborhoods. According to Reuters, demonstrations erupted over the exclusion of Samia Suluhu Hassan’s two biggest challengers and what protesters called growing government repression. Police fired tear gas and live rounds, ordered a city‑wide curfew, and witnesses reported fires at government offices and buildings. The anger spread north to Arusha and Mwanza, cities with their own traditions of student activism and labor unrest. Videos slipped past the internet blackout: police firing live rounds, bodies on the pavement, unarmed protesters dragging the wounded out of gunfire. Hospitals filled up; Journalists disappeared behind the shutdown of communication channels.

Opposition groups and rights coalitions allege as many as 3,000 deaths; CHADEMA, the main opposition party, claims that over 1,000 people were killed, and the United Nations Human Rights Office confirms at least 10 killed by live fire. The government dismisses the higher estimates as ‘hugely exaggerated’ and has yet to publish an official death toll. Reuters and the BBC both report that no credible independent casualty figure is available The real number likely lies somewhere between those estimates, buried with the bodies no one is allowed to count.

For nearly five days, Tanzania was cut off from the world. Internet access was cut off nationwide, confirmed by digital‑rights monitors and the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, leaving TikTok, X, WhatsApp, and Signal dead across the country. Banks and schools closed, flights were grounded, and even government websites went offline. For almost a week, the nation wasn’t just silenced; it was isolated from itself.

When Samia took her oath of office a week later in Dodoma, it was held at the Tanzania People’s Defence Force parade grounds. An unprecedented choice that underscored control over ceremony. The event was closed to the public, ringed with soldiers, and broadcast to the nation under heavy security. Her 97.66% victory wasn’t a democratic mandate; it was a statement of dominance. The reformist mask was gone.

manufacturing the enemy

As the death toll rose, the government reached for an old script. State House officials blamed what they called “foreign elements,” suggesting that actors from Kenya, Uganda, and certain Western NGOs were behind the unrest. Foreign Minister Mahmoud Thabit Kombo dismissed opposition death tolls as “hugely exaggerated” and claimed the violence was the work of “criminal elements” and cross-border interference. A familiar Magufuli‑era narrative reframed for the moment.

The blackouts and arrests made verification impossible, which is the point. Confusion is control. If the world can’t see who’s dying or why, the government can fill the vacuum with whatever story it wants.

At the end of the day, foreign plot or not, the anger is justified. If the state truly feared infiltration, it could have defused it by governing decently. By feeding people, creating jobs, and reining in the corruption that fuels despair. A government whose citizens believe in it doesn’t fear outsiders; people who love their country defend it from within. Only a government that has failed its own citizens worries that outsiders can sway them. When a state neglects its people, outside influence isn’t what breaks it; it’s what exposes it. The fury in the streets was earned.

The anger comes from real, visible problems. Corruption in Tanzania isn’t just a news story, it means medicine that never reaches clinics, schools that never get repaired, and public contracts handed to friends of the ruling party. It drains public money, makes people lose faith in their leaders, and turns even simple paperwork into a waiting game for bribes. For young people facing high unemployment and rising prices, corruption feels like the reason life keeps getting harder. Compared with neighbors, Tanzania may look average on global corruption rankings, less corrupt than Kenya or Uganda, though not as tightly controlled as Rwanda, but for most people the result is the same: fewer services, higher prices, and a government that grows more distant. The protests weren’t imported. They were born from that frustration.

the economics of control

As violence shut down the ports and airports, the losses piled up. Analysts estimate that Tanzania lost roughly $30-35 million dollars a day during the blackout week, mainly from the disruption of trade, digital payments, and logistics. Small traders couldn’t process transactions, food shipments were delayed, and fuel prices spiked overnight.

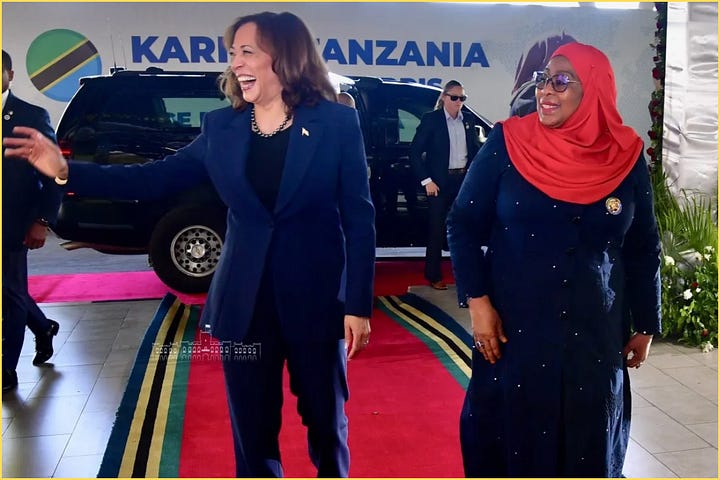

At that moment, as violence escalated and economic losses mounted, the government no longer acted out of economic reasoning, it was driven by political survival. Washington once praised Samia’s early reforms under Biden, but that goodwill evaporated amid the bloodshed and with Trump now back in power, even that limited goodwill no longer matters.

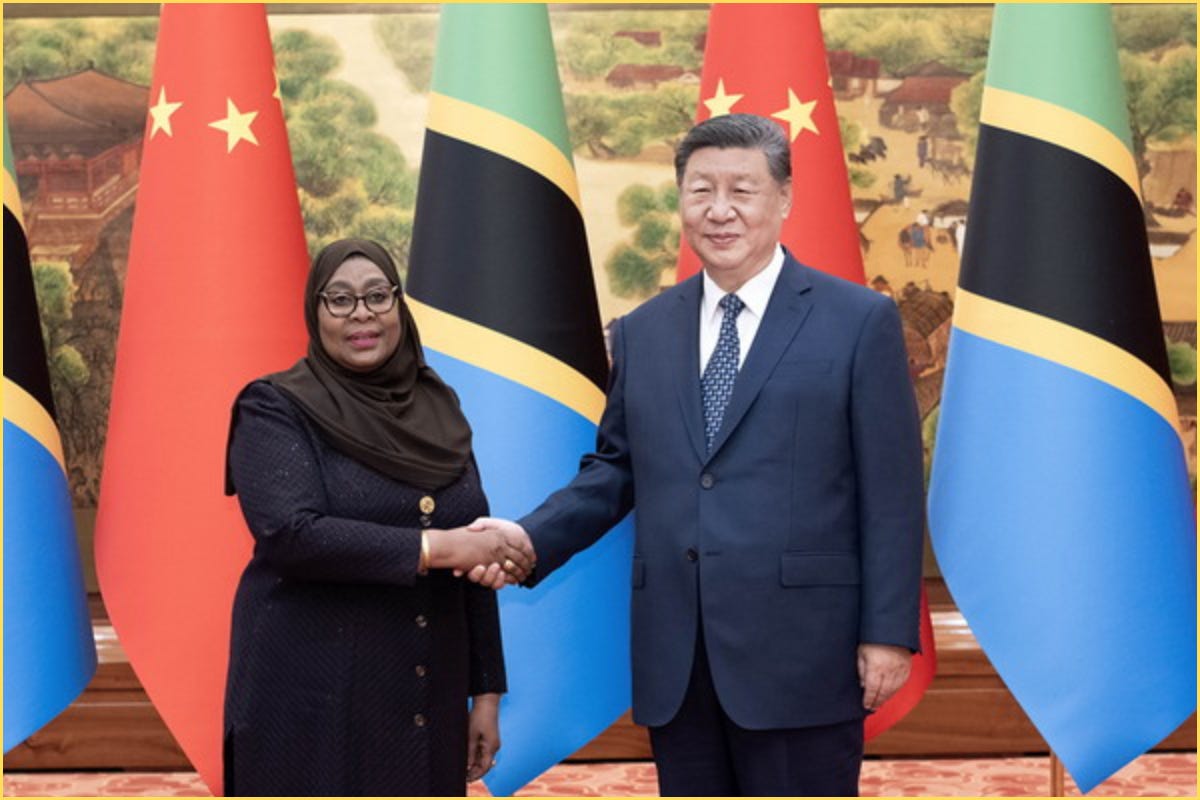

The U.S. was never Tanzania’s main pillar of support anyways. Since Nyerere, CCM governments have followed a path of deliberate non‑alignment, balancing Western aid with partnerships with China, Russia, India, and the Gulf. Samia has simply expanded that balance. This year, she launched a $1.2 billion uranium project with Russia’s Rosatom and signed new economic trade pacts with China’s Shaanxi Province. Her strengthening partnerships with China and Russia show a pragmatic strategy to secure and bolster allies beyond Western influence. This is less a pivot than a continuation of Tanzania’s long-standing independent foreign policy.

At the same time, Tanzania’s relationship with India has deepened. Bilateral trade reached nearly $9 billion in 2024, with both governments aiming to push it past $10 billion through new energy, port, and defense cooperation. India’s investments in ICT, maritime security, and infrastructure in Dar es Salaam give Tanzania another key partner. One blending strategic alignment with historical and educational ties dating back to the Nyerere–Nehru era.

What Samia is doing is an intensification of Tanzania’s traditional non‑aligned stance. U.S. statements now sound cautious instead of commanding, stripped of real leverage. The U.S. Embassy’s October 30 alert urged citizens to shelter in place during election violence, and a follow-up advisory raised Tanzania to Level 3, warnings meant to protect tourists, not pressure power. Senator Jeanne Shaheen called the election ‘fraudulent’ and urged a review of U.S.–Tanzania relations. Yet beyond rhetoric, Washington imposed no real consequences. Samia no longer seeks Western approval and her independence shows it.

China and India, meanwhile, reacted along expected lines. Chinese President Xi Jinping congratulated Samia, emphasizing stability and continued cooperation, an approach consistent with Beijing’s focus on safeguarding its long-term investments in Tanzanian ports, railways, and mining projects. India also refrained from public criticism, instead highlighting its deepening trade and defense ties and new business forums. Both responses underscored Tanzania’s strategic leverage. China and India, its first and second largest trading partners, prioritize continuity and access over democratic reform, and for Samia, that quiet endorsement is as valuable as open support.

Tanzania may not be a top-tier player in the U.S.–China Cold War, but its geography makes it a quiet battleground. Its ports, railways, and gas fields form vital corridors that both powers depend on. Dar es Salaam links six landlocked neighbors, and the same routes carry copper and cobalt from Zambia and the DRC to global markets. The upcoming LNG terminals could supply a good amount of international demand for decades.

For Washington, a reformist government like Tundu Lissu’s might look like a chance for cleaner contracts and easier entry for Western investment in LNG, mining, and logistics. But that doesn’t mean the U.S. would actually get what it wants. American investors still face high costs, heavy bureaucracy, and deep Chinese entrenchment that won’t disappear overnight.

For Beijing, a reformist shift would trigger renegotiations, not withdrawal. China holds a dominant role in Tanzania’s rail-infrastructure and has major stakes in its broader transport and industrial networks, including significant port and logistics projects. China won’t just walk away. Its long game has always been clear, build so much critical infrastructure that no government, no matter how friendly to the West, can afford to cut ties. Tanzania’s leverage lies in this balance. Whichever power invests without demanding loyalty will shape its next chapter. That equilibrium keeps Tanzania quietly pivotal in the U.S.–China rivalry. They are able to draw concessions from both sides while keeping its sovereignty intact. Beijing wants lasting access to minerals and infrastructure; Washington wants governance reforms to secure its stake. But in practice, Tanzania is likely to stay neutral and pragmatic, using both to serve its own interests.

a region of mirrors

What’s happening in Tanzania isn’t isolated. Across East Africa, repression travels faster than refugees. In Uganda, General Muhoozi Kainerugaba (son of President Museveni) livestreams his brutality with impunity. In Rwanda, critics vanish or turn up dead abroad. In Kenya, the police shoot protesters in daylight. Each government watches the other and learns. When Tanzanian security forces abducted Kenyan activist Boniface Mwangi and Ugandan journalist Agather Atuhaire back in May, it was a warning that dissent anywhere in the region can be punished everywhere.

If you want to see how this same pattern of power and fear plays out just across the border, read my earlier piece from May:

how museveni turned uganda into a one-family state

After nearly four decades in power, President Yoweri Museveni has reshaped Uganda’s political system to entrench personal rule, undermining constitutional checks and positioning his son, Gen. Muhoozi…

The East African Community has become less a union of trade than a cartel of impunity. For many regional leaders, regardless of ideology, the instinct is to keep Samia in power to prevent contagion. If Tanzanians can force change there, they fear their own citizens could do the same.

Across the region, leaders project confidence while revealing unease. Kenya’s government publicly called for calm and monitored trade disruptions at its border crossings with Tanzania, while Uganda’s General Muhoozi weighed in online, warning on TikTok that the “Kenyan virus” of protest had “spread to Tanzania” and cautioning Ugandans not to get ideas. His comment captured the unease of the region’s ruling elites. From Kampala to Nairobi, the situation is seen as both a warning and a reflection, showing that when prosperity fails to materialize and corruption festers, even populations once loyal can turn against their rulers faster than their militaries can respond.

Only a handful of foreign dignitaries attended Samia’s inauguration, but several heads of state were present. Zambia’s President Hakainde Hichilema, Somalia’s President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, Burundi’s President Évariste Ndayishimiye, and Mozambican President Daniel Chapo all attended in person, each citing the event as a gesture of solidarity and commitment to regional stability.

Their attendance can be interpreted as a sign that neighboring leaders valued continuity and calm over confrontation. Hichilema’s decision drew criticism at home, seen as risking his democratic credentials, yet his team framed it as an act of diplomacy and economic pragmatism given Tanzania’s key role in regional trade routes and energy corridors. For Zambia, Dar es Salaam Port remains its principal maritime gateway to global markets, making Tanzania indispensable to Zambia’s access to the outside world. Burundi shared this reasoning, reliant on Tanzanian trade and transport links, while Somalia’s motivation was different. Tanzania has signed defence and security cooperation agreements with Somalia and pledged to support Mogadishu’s anti‑insurgency strategy under the African Union framework, even though it has not formally deployed combat troops there. Mogadishu’s leadership viewed continued partnership and stability as essential to maintaining regional security and counter‑terrorism coordination.

For Mozambique under President Chapo, Tanzania remains a key strategic partner. His attendance at Samia’s inauguration reflected the enduring connection between Mozambique’s FRELIMO and Tanzania’s CCM, two liberation movements turned ruling parties whose socialist ideals once promised equality but over time gave way to entrenched corruption and single‑party dominance. Chapo’s participation also echoed Mozambique’s own recent trajectory with allegations of election rigging, elite capture of resource wealth, and the erosion of the socialist promise that once defined FRELIMO, traded away for corruption and the worst forms of predatory capitalism.

As explored in my May article, Mozambique faces the same foreign‑driven extraction and entrenched corruption as Tanzania. Only deeper, harsher, and more transparent in its decay:

mozambique is rich in gas. that doesn’t mean it’s winning.

Mozambique is hosting a gas boom. But it isn’t Mozambique that’s booming.

For these nations, a stable Tanzania under Samia meant preserving essential alliances, making silence safer than protest. Kenya’s President William Ruto congratulated Samia by phone shortly after the election. Days later, he told Kenyan media that “you can never get 96% in a democracy,” a pointed comment on Tanzania’s 97–98% tally that signaled polite recognition rather than approval. When it came to the inauguration itself, he sent his deputy, Kithure Kindiki, to represent Kenya, a cautious show of diplomacy without full political embrace. From Uganda, President Yoweri Museveni also stayed home, dispatching Vice President Jessica Alupo to attend on his behalf, while publicly praising Samia’s reelection on X and emphasizing trade and integration ties.

Together, these responses reflected a broader calculation among East African leaders: support for Samia meant preserving the status quo. For them, Tanzania’s turmoil was not just her crisis, each understands that if Tanzania’s uprising succeeds, the shockwaves could reach their own capitals next.

after the inferno

Two weeks after the election, Dar es Salaam is quieter, but not calm. The blackouts have lifted; the fear hasn’t. According to Reuters and Al Jazeera reports, between 98 and more than 200 protesters have been charged with treason following the post‑election unrest. Those charged include activists, business owners, and online personalities accused of obstructing the election, offences that carry potential capital sentences under Tanzanian law.

The African Union and SADC both concluded the election failed to meet democratic standards, citing ballot stuffing, abductions, and the internet blackout. CHADEMA’s offices remain sealed. Tundu Lissu’s trial drags on in a court whose verdict was written months ago.

The African Union has called for “dialogue.” Western governments have returned to the business language of “stability,” “partnership,” “security cooperation.” In other words, back to normal.

But the illusion that Tanzania was reforming has burned away. Samia now rules openly as what she became: an autocrat. For the citizens who marched under No Reforms, No Election, there’s nothing left to lose but fear, but even in that loss, something remains: the shared conviction that their unity means power, and that fear, once broken, can never be restored.

What sets this uprising apart from those in Kenya or Uganda is its rare unity. Tanzanians are not divided along ethnic or sectarian lines, the legacy of Nyerere’s nation-building still endures. That cohesion makes the protests both potent and historic: a generation standing together without tribal banners or inherited grudges. Gen Z across the region may be restless, but Tanzania’s defiance carries a deeper history, one of shared identity and national pride forged decades ago, now revived in the streets.

The regime might survive this year. It might even grow richer through new deals and alliances. But the compact that once held the country together, the quiet belief that silence meant safety and progress, is broken. Still, this could be the moment that forces Samia to confront her real enemy, not protesters or foreign critics, but the corruption eating her government from within. If she takes it as a warning rather than a verdict, if she chooses to cleanse the rot instead of deny it, she might yet rewrite her legacy.

Tanzania doesn’t need another strong hand, it needs clean ones. Whether she listens or not will decide what this silence becomes next: the calm before renewal, or the pause before collapse.