what did museveni just say?

how one remark exposed a growing fault line in east african geopolitics.

Uganda’s president didn’t misspeak. He didn’t get carried away. He wasn’t joking. Yoweri Museveni, one of Africa’s longest-ruling leaders, looked straight at the microphone this week and declared that the Indian Ocean “belongs to me,” that Uganda has been “locked out of what rightfully belongs to us,” and that if this continues, “in the future we may have wars.”

It was the kind of statement that makes a region pause. Because if you strip away the metaphors and the old-man storytelling, Museveni was talking about Kenya. He was talking openly, directly, and without the diplomatic padding African leaders usually hide behind. He was saying that Kenya sits on a coastline that Uganda needs, deserves, and might one day fight over.

For Kenya, the remark landed abruptly, forcing Nairobi to confront a level of rhetoric it did not anticipate. For Uganda, the statement functioned as a public release of long‑standing frustration, a political expression rather than an emotional one. But for East Africa, it was something else. A warning about the new political economy forming in the region, where geography is becoming destiny again, and the leaders of landlocked states are no longer pretending to be comfortable with it.

Museveni framed his argument in the language of injustice. He compared Uganda to an upper-floor resident in an apartment building, someone entitled to use the shared compound but prevented from reaching it because the ground-floor neighbor controls the only direct access. Kenya, he suggested, had taken more than its share, acting as if the ocean were its private property. This wasn’t a technical conversation about port fees or customs delays. It was a fundamental question of sovereignty, narrated as a story of exclusion.

And that is what made it so explosive.

Kenya responded cautiously, with Prime Cabinet Secretary Musalia Mudavadi reiterating that Kenya has no intention of obstructing Uganda’s use of the Port of Mombasa and noting that international conventions guarantee the rights of landlocked states. His remarks echoed Kenya’s long‑standing position rather than signaling any policy shift. Kenya’s response offered reassurance but did not engage with the deeper issue Museveni raised: that Uganda remains vulnerable because its main trade infrastructure lies entirely outside its borders.

A significant share of Uganda’s external commerce, particularly fuel imports and containerized goods, continues to move through Kenyan territory via the Port of Mombasa and its connected transport corridors. In 2024, Uganda accounted for roughly two‑thirds of all transit cargo handled at the Port of Mombasa, about 8.8 million tons out of 13.4 million, according to Kenyan port data. This scale of reliance illustrates how central the Mombasa corridor remains to Uganda’s external trade, even as Kampala explores gradual diversification through Tanzania’s Port of Dar es Salaam. The dependence itself is not new; it has defined Uganda’s trade geography for decades. What is new is Museveni’s decision to elevate this reliance from a logistical reality to a strategic grievance, framing it as a vulnerability that carries political weight rather than merely an economic cost.

The timing of all this isn’t accidental. Museveni is entering another election cycle, having already confirmed earlier this year that he intends to run again. At 81 and amid growing signs of public fatigue with his decades-long rule, he has every incentive to lean on nationalist rhetoric, especially rhetoric that reframes external constraints as historical injustices only he is strong enough to confront. Raising the sea‑access issue now functions as political mobilization, a way to turn a structural vulnerability into an electoral rallying point and cast himself as the sole defender of Uganda’s sovereignty.

Across the region, something is happening. Ethiopia, the most populous landlocked state on Earth, is relentlessly pushing its argument for Red Sea access. Not only to reshape its regional position but to consolidate internal cohesion at a time of political fragmentation. Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has framed port access as an existential matter, using it to rebuild nationalist energy after years of internal conflict, ethnic fractures and declining public trust. By turning maritime access into a question of identity and historical justice, Ethiopia normalized the idea that losing a coastline is an injury that must be politically corrected. Once that framing entered the regional bloodstream, it gave other leaders permission to speak the same way. Museveni watched that shift, recognized how effectively it redirected domestic frustration outward, and decided it was his moment too.

Uganda’s situation is not uniquely personal, nor is it distinct in a way that sets it apart from other landlocked states in the region. Museveni’s statement that “the ocean belongs to me” should therefore be understood not as a special case of bilateral tension with Kenya, but as part of a broader discourse shared by landlocked countries seeking to challenge long‑standing structural disadvantages. His rhetoric mirrors a regional pattern, exemplified most clearly by Ethiopia’s recent posture, where questions of access, dependency, and sovereignty are being reframed as political grievances rather than technical constraints. The intention is to highlight imbalance, assert agency, and shift the debate toward rights and entitlements.

This framing matters because it shows how maritime access is becoming a wider regional argument rather than an isolated dispute between two states.

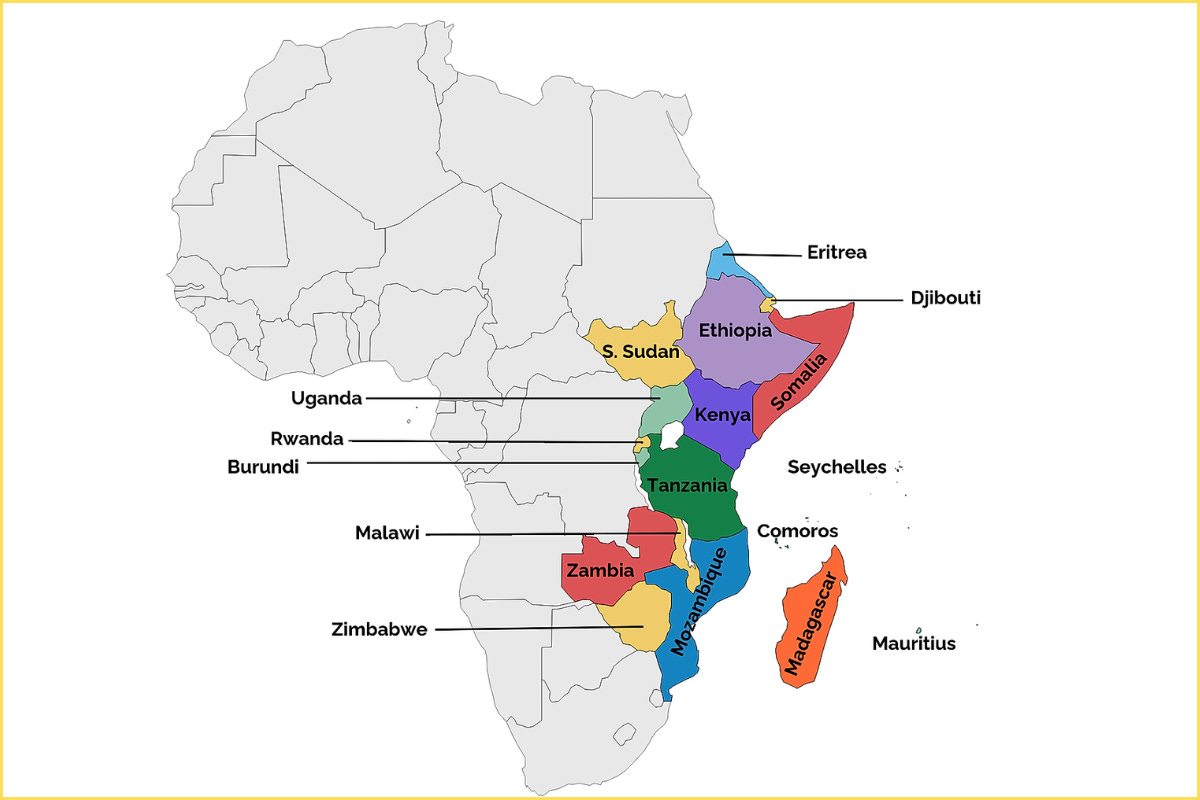

Across the region, competition over ports, transit corridors, and access routes is becoming increasingly prominent in regional politics. Coastal states such as Kenya, Tanzania, Eritrea, Djibouti, Sudan and Somalia serve as logistical gateways for trade, giving them structural advantages within regional supply chains. Landlocked states including Uganda, Ethiopia, Rwanda, Burundi, Zambia, Chad and South Sudan continue to rely on these coastal corridors for the bulk of their imports and exports. While this does not necessarily indicate that future conflicts will center on maritime access, it does show that questions of transit rights, infrastructure control, and economic vulnerability are becoming more central to regional debates and diplomatic positioning.

Museveni’s comments should be understood through that lens. He is not preparing to invade Kenya. But he is announcing, loudly, that Uganda will no longer pretend to be content with the arrangement. He is signaling that the age of quiet acceptance is over and he is placing Kenya in a position where doing nothing now looks like arrogance, and doing something looks like concession.

A broader shift is occurring in African politics, one in which maritime access is becoming a strategic concern, a kind of maritime nationalism that feels both inevitable and destabilizing at the same time. Ethiopia wants the Red Sea. Uganda wants the Indian Ocean. Kenya and Eritrea are being forced into defensive postures they didn’t choose. And external powers like the UAE, US, Israel, China, India, Turkey and Russia see opportunity in the friction. Ports are the new oil wells. Maritime corridors are the new borders.

In this context, when Museveni said “the ocean belongs to me,” he wasn’t joking, and he wasn’t rambling, he was unveiling a grievance decades in the making, shaped by an economy built on someone else’s shoreline. He was telling Kenya that Uganda’s patience has limits. And he was telling the rest of the region that the politics of water, who can reach it, who controls it, who depends on it, will define the next phase of East African geopolitics.

How this moment develops will depend on diplomatic choices and regional economic planning rather than immediate confrontation. It is also possible that the intensity of this rhetoric will fade if leaders, whether in Kampala or Addis Ababa, feel they have regained firm control at home and no longer need to rely on nationalist narratives to consolidate support. But what this moment reveals, regardless of whether the tension escalates or dies down, is that the old geography is being questioned. Museveni’s remarks ensured that the region can no longer avoid that conversation.

For readers who want the broader context of Museveni’s internal power architecture, the full report is linked below:

how museveni turned uganda into a one-family state

After nearly four decades in power, President Yoweri Museveni has reshaped Uganda’s political system to entrench personal rule, undermining constitutional checks and positioning his son, Gen. Muhoozi…

For readers who want the deeper picture of Uganda’s external strategy across the region, the full analysis is linked below:

the general who outgrew uganda

On May 3, airstrikes hit Old Fangak, a remote town in South Sudan’s Upper Nile state. The only hospital in the area, run by Médecins Sans Frontières, was destroyed, killing at least seven and woundin…